This week, the Cumulative Environmental Management Association (CEMA), an industry-funded consultancy group in Alberta, released the End Pit Lakes Guidance Document to the Government of Alberta for review. The 434-page document outlines a 100-year plan to integrate open-pit mines and tar sands tailings into Northern Alberta’s local ecosystem, introducing what they call a ‘reclaimed lake district’ as a long-term alternative to the temporary tailings ponds that currently hold the billions of gallons of water, sand, clay, hydrocarbons, naphthenic acids, salt and other byproducts of the bitumen extraction and upgrading process.

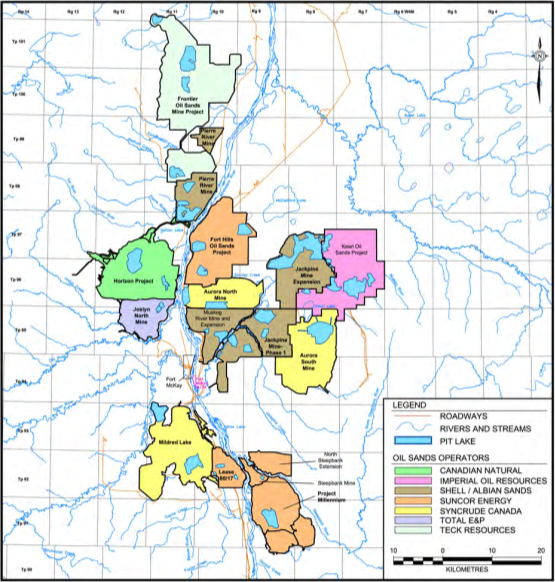

The 30 proposed end-pit lakes (EPLs) will take up more than 100 square kilometers, spread out over an area of 2,500 square kilometers. Toronto, for comparison, covers an area of 630 square kilometers.

Industry envisions the artificial lake district as a future recreation site, although there is no indication yet that filling empty open-pit mines with freshwater will give way to the clean natural environments necessary to promote recreational uses of the area. In fact, The Globe and Mail reports the document “highlights the scale of the ecological gamble underway in the province” and suggests the technique is being considered as a remediation option because “it’s less costly to fill a mine with water than dirt.”

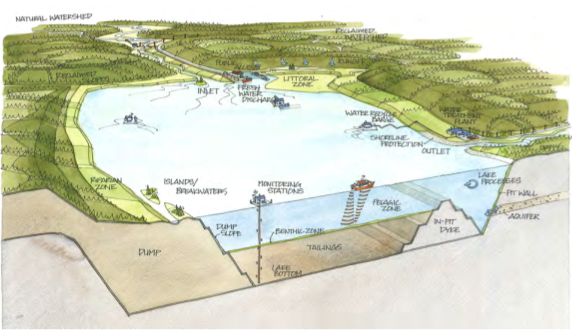

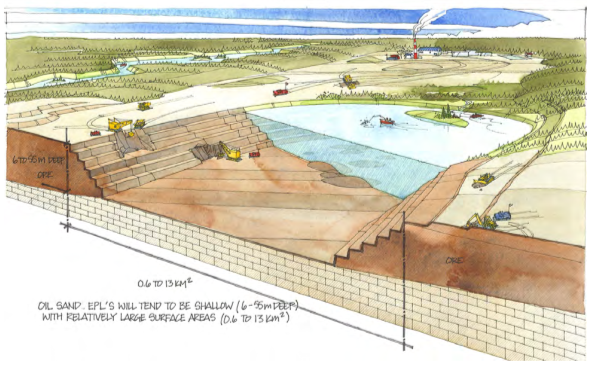

The CEMA document describes an EPL as “An engineered water body, located below grade in an oil sands post-mining pit. It may contain oil sands by-product material and will receive surface groundwater from surrounding reclaimed and undisturbed landscapes. EPLs will be permanent features in the final reclaimed landscape, discharging water to the downstream environment.”

The basic EPL “scenario” involves capping bitumen byproduct with freshwater. Surface runoff, rain, groundwater and tailings waste are all considered “inputs” to which CEMA suggests operators may add “process-related materials” such as “tailings deposits, tailings sand, lean oilsands, petroleum coke and process-affected waters that remain at the end of mine operations.”

The operational logic behind the plan banks on the fact that bitumen waste will sink and release remaining water to the “water cap” where natural processes will accomplish the majority of the remedial work.

Whether or not the plan will work is entirely unknown and veiled in “scientific uncertainty,” according to CEMA. The “potential for substantial negative and environmental and/or social impacts,” they add, is “likely” for EPLs and thus decision-makers should employ the “precautionary approach.” It is anticipated that the success or failure of these toxic installations will not be known until decades after their construction.

The scope of CEMA‘s vast watershed experiment emphasizes the severity of the impact tar sands development has on the landscape as well as the absence of alternative reclamation plans.

Syncrude, the largest operator in the tar sands, has already begun experimenting with the process in preparation for the first-ever end pit lake slated for construction in the next few months. The company’s ‘base mine lake,’ which covers 40 vertical meters, will be ‘capped’ with fresh water and developed into an EPL.

“The major purpose of this [base mine lake] demonstration is to help understand and define these timeline,” Warren Zubot, senior Syncrude engineering associate, told The Globe and Mail. “We’re very confident this technology is going to work.”

A previous Syncrude experimental pond was so successful it was able to support rainbow trout after one year, according to Zubot.

Scientists, environmental groups, and local communities and First Nations are somewhat less optimistic about the plan.

“The basic concern,” Carolyn Campbell from the Alberta Wilderness Association (AWA) told DeSmog, “is that end pit lakes with tailings at the bottom will release toxins such as naphthenic acids from tailings into the environment, to the detriment of ecosystems generally. And so many end pit lakes have been approved on sheer faith rather than demonstrable results that it’s creating a potential huge environmental liability.”

“It’s going to be a completely alien landscape,” said Peter Fortna, who works with local Métis in nearby Fort McKay. “They try to find the cheapest option as opposed to the best option.”

Dr. David Schindler of the University of Alberta also remains skeptical these disposal pits can furnish healthy ecosystems in the long term. “We must have some assurance that they will eventually support a healthy ecosystem,” he said, adding to date there is no “evidence to support their viability, or the ‘modelled’ results suggesting that outflow from the lakes will be non-toxic,” reports The Globe and Mail.

The CEMA report acknowledges there is little certainty regarding the long-term disposition of bitumen byproducts in lake beds. The toxic residue may migrate to shallow or surface areas. The report cites “the sudden occurrence of bitumen slicks on Suncor’s 20-year-old sustainability ponds after years of bitumen-free surface conditions.”

It would remain the government’s prerogative to determine whether or not the lakes, after decades of natural modification, can be certified environmentally sustainable.

Yet even the return to a non-toxic environment in the tar sands area will still have severe adverse impacts on species that require peatland and muskeg for their survival. Woodland caribou, which are being wiped out in the tar sands region because of industrial expansion, are one such species. Section 4.2.4 of the CEMA report (pg. 108) outlines affected wildlife species without even mentioning caribou.

Campbell from AWA adds “the reclamation phrase ‘Returning mineable oilsands in the Athabasca oilsands region to a state functionally equivalent to the natural conditions that characterize the boreal forest of northern Alberta…’ in the [CEMA] media release is misleading in that the reclaimed landscapes will lack freshwater peat wetlands that make up over half of the pre-disturbance landscape, will be species poor compared to the pre-disturbance landscape, and will lack the carbon storage and carbon sequestration capacity of the pre-disturbance landscape.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts