ExxonMobil is getting defensive about its response plans for the tar sands pipeline spill in Arkansas. The company took to Twitter this afternoon to respond to what it called “allegations” that Exxon isn’t liable for the full costs of cleaning up their tar sands crude spill in Mayflower, Arkansas.

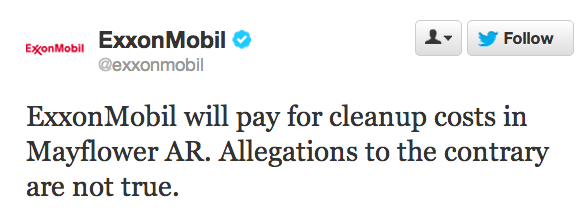

Here’s the tweet from @exxonmobil sent in response to critics who pointed out that, because of a major loophole that needs to be closed, bitumen is not considered crude oil, and therefore tar sands pipeline operators like Exxon aren’t required to pay into the oil spill cleanup fund.

A couple of things to unpack here.

First, most of the “allegations” that Exxon Mobil is referring to are actually criticisms of how the company didn’t pay into a federal oil spill cleanup fund for the dilbit that traveled through the Pegasus pipeline.

This was first brought to light by Oil Change International (and soon echoed by Ryan Koronowski on Climate Progress and then by Carol Linnitt on DeSmog Canada), all of whom explained the bizarre technicality that exempts dilbit (or diluted bitumen, the transportable form of tar sands crude) from the taxes that fund the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund.

As Oil Change International said in a statement released yesterday:

The great irony of this tragic spill in Arkansas is that the transport of tar sands oil through pipelines in the US is exempt from payments into the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund. Exxon, like all companies shipping toxic tar sands, doesn’t have to pay into the fund that will cover most of the clean up costs for the pipeline’s inevitable spills.

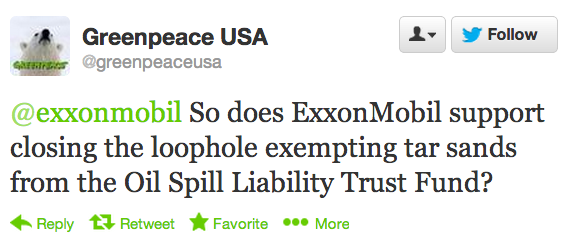

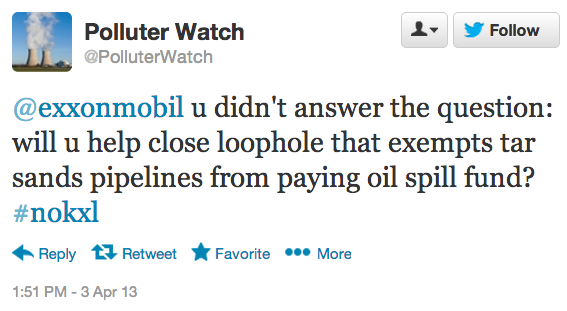

Responding to ExxonMobil’s dodgy tweet, Greenpeace and PolluterWatch posed some important questions:

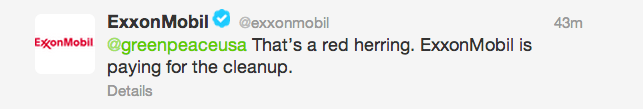

To which ExxonMobil combatively replied:

So, if ExxonMobil wants some real allegations that they won’t be paying the full costs of cleanup and the subsequent damages to property and lives in Mayflower, well, we’re happy to oblige.

The company’s history certainly makes such an allegation easy to make – ExxonMobil doesn’t exactly have the best track record of cleaning up their mess.

Remember Exxon Valdez?

Where to begin? How about Valdez, Alaska? Time for a quick refresher on what happened there, and how Exxon continually and systematically delayed and fought against payouts. From Climate Progress back in 2010:

The Exxon Valdez tanker spilled more than 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound, which eventually contaminated approximately 1,300 miles of shoreline. The total costs of Exxon Valdez, including both cleanup and also “fines, penalties and claims settlements,” ran as much as $7 billion. Cleanup of the affected region alone cost at least $2.5 billion, and much oil remains.

Yet Exxon made high profits even in the aftermath of the most expensive oil spill in history. They made $3.8 billion profit in 1989 and $5 billion in 1990. And this occurred while Exxon disputed cleanup costs nearly every step of the way.

Exxon fought paying damages and appealed court decisions multiple times, and they have still not paid in full. Years of fighting and court appeals on Exxon’s part finally concluded with a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2008 that found that Exxon only had to pay $507.5 million of the original 1994 court decree for $5 billion in punitive damages. And as of 2009, Exxon had paid only$383 million of this $507.5 million to those who sued, stalling on the rest and fighting the $500 million in interest owed to fishermen and other small businesses from more than 12 years of litigation.

Twenty years later, some of the original plaintiffs are no longer alive to receive, or continue fighting for, their damages. An estimated 8,000 of the original Exxon Valdez plaintiffs have diedsince the spill while waiting for their compensation as Exxon fought them in court.

But Valdez was a long time ago. What about more recent history? In 2006, a fuel line leak at an Exxon service station in Jacksonville, Maryland (that the company hid from the public for five weeks) released 26,000 gallons of gasoline underground, severely polluting local groundwater and causing irreparable damages to many local homes. The company paid $46 million for cleanup, but fought hard in the courts to avoid paying any subsequent damages. The company successfully scuttled two separate law suits on appeals processes, winning the latter claim just this past February.

Remember Exxon’s Yellowstone River pipeline spill?

Even more recently, you’ll recall the ExxonMobil pipeline that leaked 63,000 gallons of crude directly into Montana’s iconic Yellowstone River. Again, the company put forth $135 million for immediate cleanup costs (and repair work for the line, so that they could get it back in operation as soon as possible), but balked at the prospect of paying for damages.

So we might ask ExxonMobil not only if they’ll pay for the “cleanup costs” as they narrowly define them, but if they’ll make it right for the residents of Mayflower.

According to CNN, “Exxon Mobil met with displaced residents over the weekend to explain how they can make claims for losses.” The company’s president Gary Pruessing told them, “If you have been harmed by this spill then we’re going to look at how to make that right.”

Recent history would indicate that it’ll take a whole lot of lawsuits and many years for the affected residents to get compensated, if at all, for the very real damages to their properties and their lives.

Photo: Karen Segrave, Greenpeace

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts