After generations of state control, Mexico’s vast oil and gas reserves will soon open for business to the international market.

In December 2013, Mexico’s Congress voted to break up the longstanding monopoly held by the state-owned oil giant Petroleos Mexicanos — commonly called Pemex — and to open the nation’s oil and gas reserves to foreign companies.

The constitutional reforms appear likely to kickstart a historic hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and deepwater offshore oil and gas drilling bonanza off the Gulf of Mexico.

“This reform marks a major breakthrough in Mexico’s economic history only comparable to the signing of the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1992,” international investing and banking giant Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) wrote in a January 2014 economic analysis.

What does this mean for the oil and gas industry in Mexico? And for the workers and those who live above these oil and gas plays or along the pipeline routes that will funnel the liquids to refineries? And how about for the Earth’s atmosphere?

Can Mexico’s fossil fuel infrastructure handle the boom? Can the country spare the precious freshwater supplies needed for thirsty fracking operations in an era of increasingly severe droughts and drinking water shortages? Can environmental, safety and public health regulations possibly keep up with this industrial boom?

DeSmogBlog will examine all these issues and more as Mexico opens its fossil fuel reserves to international exploitation in the weeks and months ahead. But, first, an overview of the state of play in Mexico’s energy reforms.

Full Circle: History of Mexican Energy Reforms

The contemporary history of Mexico’s energy industry started in 1938 when the federal government kicked out foreign oil companies and nationalized the oil and gas sector under the Pemex banner.

As a recent report published by the Congressional Research Service explains, nationalization occurred in the aftermath of a bitter labor dispute between Mexican workers and the international oil and gas firms who wanted to gain a foothold in the country.

“Tensions culminated in President Lázaro Cárdenas’ historic 1938 decision to abandon efforts to mediate a bitter labor dispute between Mexican oil workers and foreign companies and instead follow through on his threat to expropriate all U.S. and other foreign oil assets in Mexico,” the report explains.

President Lázaro Cárdenas; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

“Upon its creation in 1938, Pemex became a symbol of national pride and…united a disparate Mexican society against foreign intervention.”

For 75 years, Pemex alone had access to Mexico’s massive oil and gas reserves. Mexico is the world’s 9th largest producer of oil and revenues from developing the resource fund roughly one-third of the country’s budget.

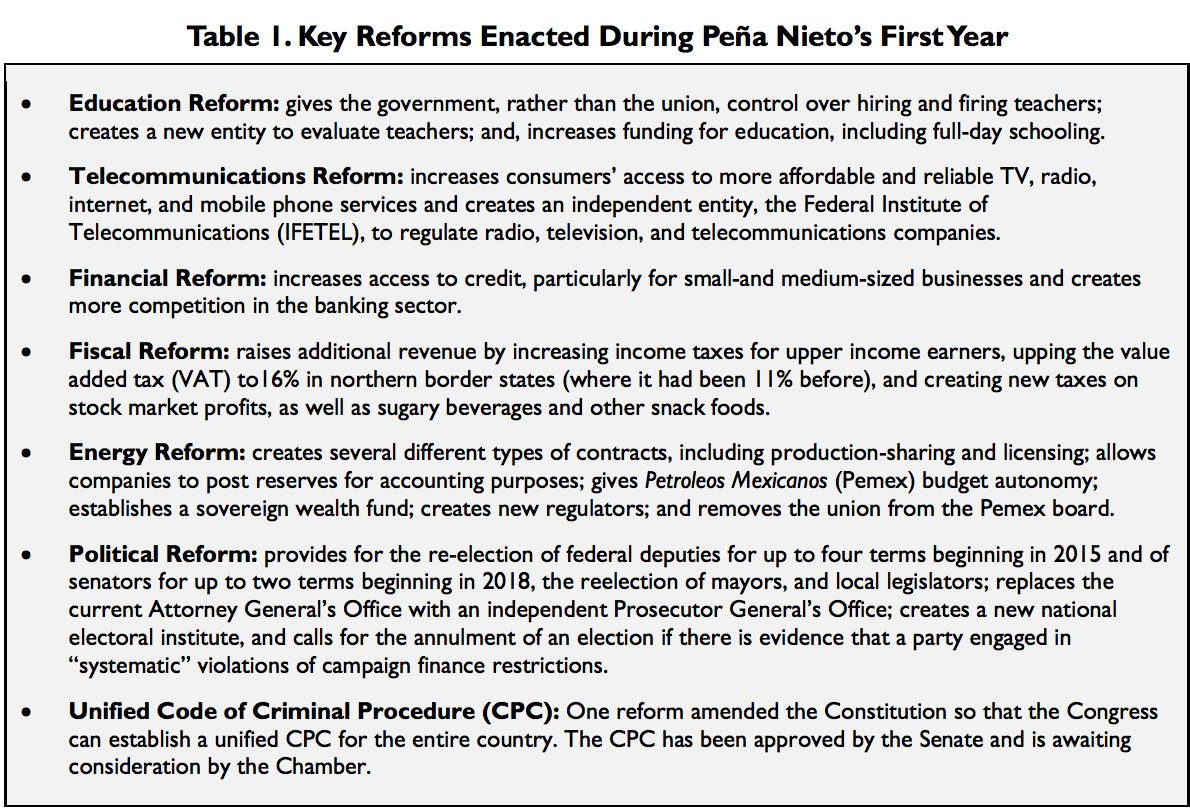

But Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), elected in July 2013, has made the “open door” energy reforms — on top of reforms in a whole host of other policy spheres — a top priority for his administration as part of his “Pact for Mexico.”

Table Credit: U.S. Congressional Research Service

There’s some historical irony at play here: Nieto’s PRI is the party that originally nationalized the Mexican oil industry to begin with.

President Enrique Peña Nieto; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

And the constitutional amendments also bring labor relations full circle, as the new board of directors for Pemex won’t include union representation, even though a labor dispute served as the rationale for nationalization of the Mexican energy industry back in 1938.

All five union representatives have been removed from the board of Pemex, which is shrinking from 15 to ten members.

Gold Rush

Proponents for Mexico’s energy reforms envision a gold rush. They argue the constitutional amendments and accompanying secondary legislation still up for debate in the Mexican legislature could add as much as $35 billion in outside investment into the national coffers.

Pemex says $25 to $60 billion could come its way as a result of joint ventures it can now sign with international oil and gas companies, while the industry-funded Manhattan Institute says 2.5 million jobs and more than $1 trillion in revenue could be created by 2025.

Texas Observer investigative journalist Shannon Young is skeptical of the numbers and figures being tossed around, however.

“[E]ven without the details, the business press has predicted energy reform could bring in [billions of dollars] in private investment in Mexico,” Young wrote in February. “How that figure was reached is unclear, as is how much money investors expect to take out of Mexico.”

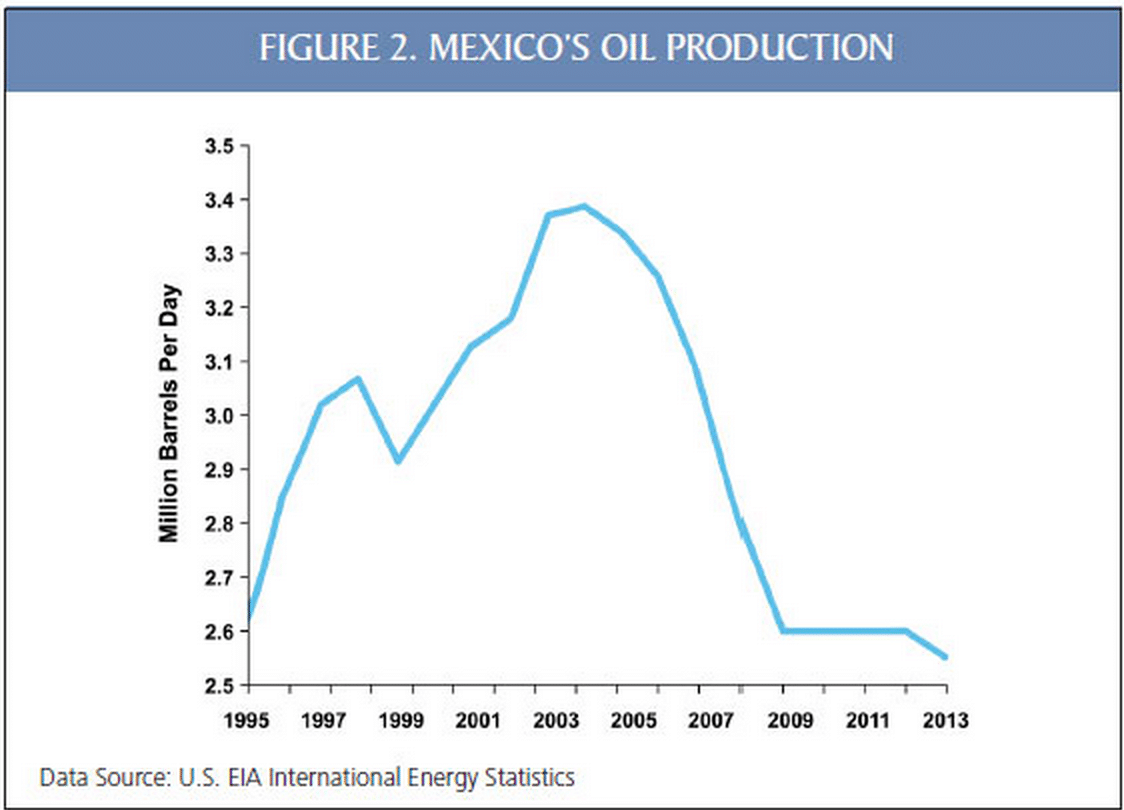

Regardless, the reforms seem certain to boost oil and gas production, which have lulled in recent years. Since reaching an all-time high in 2004, oil production has fallen by 25 percent, down to 2.5 million barrels per day today.

Table Credit: Manhattan Institute

Contrast that to Texas, just across the border. There, production increased by more than 150 percent during those same ten years, according to Daniel Yergin.

Texas’s gains are tied primarily to fracking, which has allowed drilling companies to tap into the Eagle Ford Shale and Barnett Shale basins.

Photo Credit: Shutterstock | Frank Fiedler

“We can see what is going on in the United States. Shale gas in the United States created a sense of urgency for us,” Pemex CEO Emilio Lozoya told Yergin in an article appearing in The Wall Street Journal. “We have the reserves. But we don’t have the cash and the technology to develop them.”

If the reforms bring about the production spike hoped for by Pemex and Mexican officials, the country could be among the world’s oil-producing giants by 2025.

Mexico’s Reserves: Where and How Big?

Mexico sits on nearly 14 billion barrels of oil in proven reserves, according to Pemex. The Oil and Gas Journal pegged it at 10.2 billion barrels at the end of 2011. But that’s just what they know they have.

The country’s unexplored oil reserve potential is second only to the Arctic Circle, according to Bloomberg and others reporting on the reforms.

Pemex estimates, as reported by Bloomberg, that deep-water Gulf of Mexico prospects could be as large as 26.6 billion barrels of oil. Onshore, there are potentially 60 billion barrels yet untapped.

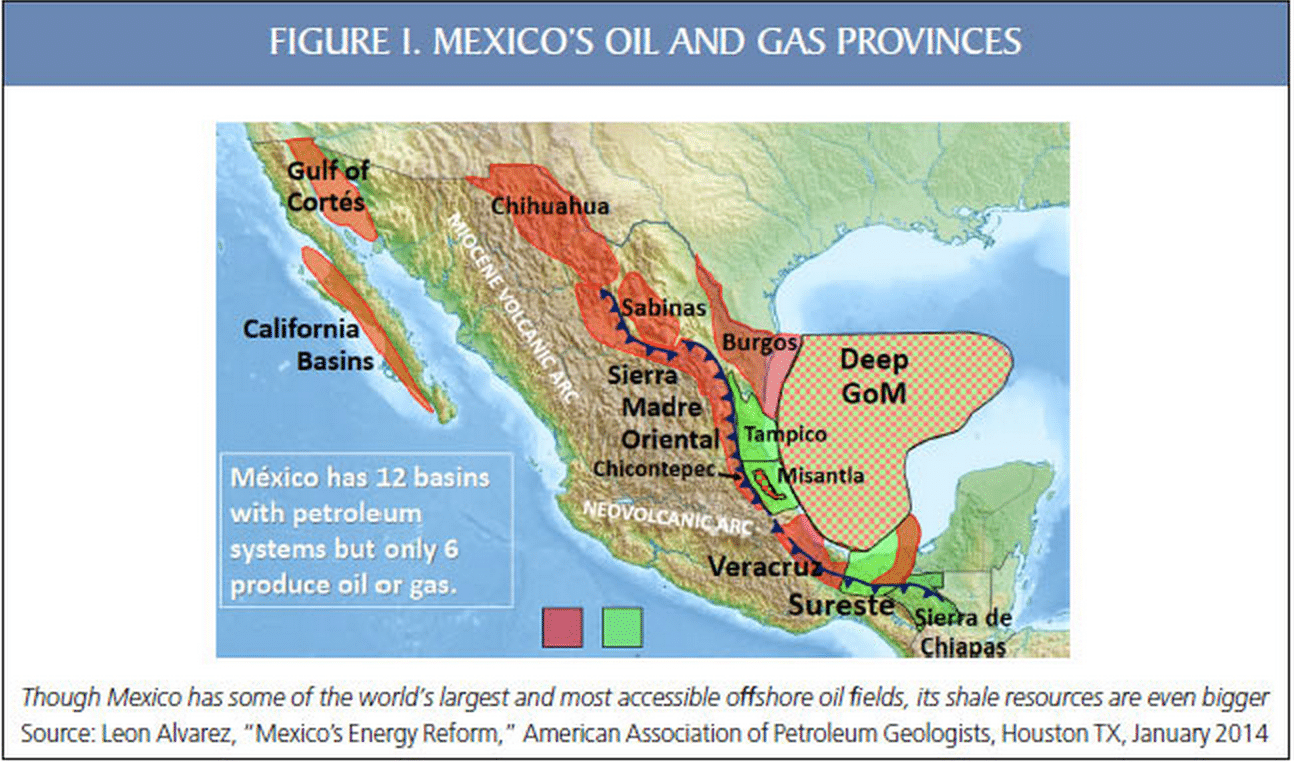

So where exactly are the goods?

Gulf of Mexico

Currently, about three-quarters of Mexico’s oil production comes from the Bay of Campeche, north of the Yucatan Peninsula, located in the states of Veracruz, Tabasco, and Campeche. In fact, more than half of the country’s oil comes from just two fields in that bay: the Ku-Maloob Zaap and the Cantarell.

As production has dropped from these conventional offshore fields, Pemex has explored in deeper waters, where the vast majority of its remaining offshore prize remains. In 2012, Pemex drillers made their first significant deep-water find in the Perdido Fold Belt, about 110 miles off the coast of the northern state of Tamaulipas and a couple dozen miles from the maritime border with the U.S.

Oil platform on Perdido Belt; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Though Pemex has rented four deepwater rigs to dig exploratory wells, experts believe that any real deep-water production will be contracted to foreign companies, which have the technical know-how to produce oil from these fields.

As part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (Section 303), President Barack Obama signed off on U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Hydrocarbons Agreement in December 2013, which “establishes a framework for U.S. offshore oil and gas companies and [Pemex] to jointly develop transboundary reservoirs.”

The bill lifts the floodgates for industry to tap into more than 1.6 million acres of offshore oil and gas.

Burgos Basin

Texas’s famous Eagle Ford Shale formation has been an epicenter of the U.S. shale boom, with accompanying health and air impacts to boot. Fossil fuel reserves don’t adhere to international demarcations, and just south of the border sits Mexico’s Burgos Basin (which Mexico calls the Boquillas formation).

Image Credit: Manhattan Institute

Pemex estimates there could be more than 300 trillion cubic feet of recoverable shale gas in the Burgos. And the U.S. Congressional Research Service pointed out in a January 2014 report that Mexico may have the fifth largest tight oil reserves and fourth largest tight gas reserves in the world.

This is largely due to the portion of the Eagle Ford formation that stretches south of the border.

Tampico-Misantla

South of the Burgos and hugging the the Gulf Coast is the Tampico-Mislanta Basin, a particularly oil-rich area that has been one of — if not the — most productive regions in all of Mexico. The so-called “Golden Lane” in the Tampico basin hosts one of the most productive wells ever drilled.

But all the easy oil is gone — which, remember, is one of the reasons why Pemex is opening up its reserves to the global market in the first place — so most of what remains is shale oil and gas.

On the western edge of these basins, and to the northeast of Mexico City, sits one of the most sought after fields in all of Mexico: the Chicontepec field.

Pemex has tried and failed many times to tap the vast crude oil reserves in the Chicontepec. But technical and financial challenges have kept the company coming up dry. Expect lots of competition for the right to exploit this particular oil field.

Veracruz

South of the Tampico-Misantla, still along the coast, sits Veracruz. Natural gas production in the Veracruz Basin maxed out in 2006.

And with just five percent of Mexico’s proven natural gas reserves, it probably won’t be the heart of a big prospecting rush like the Burgos or Chicontepec or any of the heavy-hitter offshore plays.

The Southeastern Basin

The Southeastern Basin (or Sureste Basin) has both on- and off-shore fields, including the massively productive Campeche region in the Gulf of Mexico.

Onshore prospects in the Southeastern Basin are, basically, an afterthought. There are both natural gas and oil fields, but the biggest strikes are believed to be offshore.

To summarize: While new companies looking for a foothold in Mexico are likely to explore and develop oil prospects in all regions, to some degree, the big prizes and most attention will likely center around:

- the deep-water offshore oil plays in the Gulf of Mexico;

- the shale gas plays in the Burgos Basin;

- and the tight oil and shale gas plays in the Chicontepec field.

The Players

Speaking at the recent CERAWeek energy conference in Houston, Lozoya invited the oil and gas industry big boys into Mexico with open arms.

“Capital from all over the world is welcome in Mexico,” he said. “We hope to have hundreds of companies operating in any type of rock formation, be it shale, or shallow water, or mature fields, or deep water projects.”

So what companies are likely to accept Lozoya’s invitation and cash in on the bonanza?

ExxonMobil

“Private Empire” ExxonMobil is the biggest player out there with the most resources and a massive network of international operations.

ExxonMobil has also worked in Mexico before through its chemical division. It already has an office in Mexico City and 250 employees in the country and the company has a heavy footprint in Texas’ Eagle Ford Shale and in the Gulf of Mexico.

ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

CEO Rex Tillerson told Financial Times ExxonMobil was already working with Pemex on joint studies “so we can get to know each other.”He added, “It’s going to be a long process…And if the next step provides an avenue for ExxonMobil to participate, we will.”

Chevron, Shell, BP

Business press reports Chevron is keen to tap into Mexican oil and gas. Like ExxonMobil, it already has a heavy footprint in the Eagle Ford and Gulf of Mexico.

“This is a good start,” Chevron spokesman Kurt Glaubitz told The New York Times of Mexico’s energy reforms. “We’re optimistic about the reforms that are taking place and the opportunities that Mexico is presenting to international oil companies.”

BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill aftermath; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Further, Shell and BP (of 2010 Gulf spill disaster fame) both have an armada of oil rigs hoisted in the Gulf of Mexico. Both also have extensive ownership stakes in portions of the Eagle Ford Shale, though Shell plans to sell its Eagle Ford assets.

EOG Resources

Some may remember them as Enron (now cleverly rebranded as Enron Oil and Gas, aka EOG), or as one of the most vertically integrated “cradle-to-grave” natural gas fracking companies in the U.S.

One of EOG’s biggest projects is in the Eagle Ford, just like ExxonMobil and Chevron. Which makes EOG particularly well situated to hop the border and start fracking for gas as soon as they secure the contracts.

Eni S.A.

An Italian oil company already operating in developing world nations like Libya, Nigeria, Mozambique, Congo and Vietnam, Eni S.A. also has more than 300 wells in the Gulf of Mexico. Since the reforms passed, Eni has already opened up an office in Mexico City, as well as met with the CEO of Pemex and the President of Mexico himself.

Suffice to say, Eni’s serious about Mexican oil.

Anadarko Petroleum

The massive oil explorer and producer — which once referred to local fracking opponents as “insurgents” — is already one of the largest producers of crude from deep-water wells in the Gulf of Mexico.

Counter-Insurgency Chart; Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Maritime borders are even easier to cross logistically than terrestrial ones, particularly in the aftermath of the signing of the U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Hydrocarbons Agreement. So, moving some rigs south and west to exploit Mexico’s deep offshore plays will be easy as pie.

Lukoil

The second-largest oil producer in Russia behind Rosneft is actively looking to expand its overseas footprint. In late-January, Lukoil signed a cooperation memorandum with Pemex, formalizing its interest in Mexico.

ConocoPhillips

Like other companies mentioned, ConocoPhillips has a significant presence in the Eagle Ford Shale. Experts say the company will likely make a move to tap into Mexico’s shale gas reserves.

ConocoPhillips is also very active in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico, so it’s also primed to move to Mexican waters.

However, Pemex once sued ConocoPhillips over some stolen natural gas, so it remains to be seen whether tensions will be resolved between the two companies.

Chesapeake Energy

Chesapeake Energy — one of the top producers of shale gas in the U.S. — is another giant poised to cash in on the Mexican energy rush.

Chesapeake also has some convenient connections to Pemex and other Mexican oil “big men.”

In 2011, Chesapeake bought Bronco Drilling Company, which was formerly owned in part by Mexican billionaire (and one of the world’s richest men) Carlos Slim. Slim still holds a stake in a number of Mexican oil companies and maintains close ties to Pemex.

Carlos Slim; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

GDF Suez

On April 11, French energy company GDF Suez signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Pemex to build up Mexico’s natural gas infrastructure. Mexican President Peña Nieto and French President François Hollande were both present for the signing of the deal.

French President François Hollande (Back Left) and Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto (Back Right) at MOU signing; Photo Credit: Pemex

“With this memorandum, GDF SUEZ and PEMEX have established a collaboration mechanism to work together on future common development projects such as natural gas infrastructure facilities, gas liquefaction facilities, and gas to power plants,” a GDF Suez press release explained.

Others

In its January 2014 report on the energy reform, investing and banking giant Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) listed a number of American, foreign, and multinational companies that could potentially get involved in Mexican expansion.

BBVA International Headquarters in Madrid, Spain; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

On top of some listed above, BBVA named: Hess (for deep offshore drilling); Diamond Offshore, National-Oilwell Varco, Cameron, FMC, Trico Marine, SeaDrill, TransOcean, Geoservies, Baker-Hughes, Smith International and Schlumberger (for offshore logistics and drilling); Schlumberger, Baker-Hughes, Halliburton and Weatherford International (for oilfield services).

A recent Bloomberg article reported that companies from Asia are also interested in getting in on the scramble and on the whole, “[s]maller companies will probably dominate development of Mexico’s shale gas deposits.”

“No Turning Back”

The reform laws are currently undergoing negotiations for another round of secondary legislation, which will formalize how the contracts will be awarded and how royalties and revenues will be calculated.

Recently, Pemex chose the oil and gas fields it wants to control — a process known as “round zero” — with The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg reporting Pemex wants to keep 83 percent of Mexico’s technically recoverable reserves to itself or to be shared between Pemex and other companies as part of joint ventures. Pemex also wants all of Mexico’s proven and productive reserves.

To the chagrin of some, Pemex didn’t publicly disclose which fields it desired to keep under its wings.

“The fact that Pemex didn’t reveal (the list) speaks badly about the practices of this government in terms of transparency and it’s a very bad precedent for what comes next with the reform,” Miriam Grunstein, an energy specialist who works at the Mexico City-based Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas said in an interview with Reuters.

Miriam Grunstein Dickter; Photo Credit: Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas

Reuters reported the first international bidding process will likely take place in summer 2015, covering 25,000 square kilometers.

“[Thereafter], Mexico is expected to launch an international bid round for oil and gas development rights each year through 2019, each one covering about 20,000 square km,” explained Reuters. “[T]here could be additional shale bid rounds in a given year…in line with international best practices.”

On March 12, Juan Carlos Zepeda Molina, president of Mexico’s National Hydrocarbons Commission, said Mexico was ready to release years of oil exploration testing data. It’s a major step forward as Mexico moves to open its oil and gas industry to the international players.

DeSmogBlog will be monitoring the coming bonanza closely and will cover the developments — and especially the risks, dangers and oil/gas industry wheeling and dealing — throughout this revolutionary time in the history of the North American oil and gas industry. In particular, we’ll be investigating:

- Public opposition to the energy reforms as a whole, and local opposition to drilling

- Ecological threats to ecosystems, wildlife, rivers and waterways

- Does Mexico have enough water to support fracking operations, particularly in this time of long-term drought (or desertification)?

- How will Mexico move all this oil and gas? Examining the infrastructure: pipelines, refineries, shipping terminals.

- What regulations will be enacted and enforced to protect the local environment, public health and safety?

- How will such an influx of shale gas and oil impact the global economics of liquid fossil fuels? How does this extend the lifeline of the popping of the “shale gas bubble”?

As the Atlantic Council wrote ominously in its December 2013 report titled Mexico Rising: Energy Reform at Last?, “The scale of the reform is breathtaking in its scope and ambition…It will be a bumpy road, but these reforms mean there is no turning back.”

Photo Credit: Shutterstock | GrAl

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts