While the debate over the TransCanada Keystone XL tar sands pipeline has raged on for over half a decade, pipeline giant Enbridge has quietly cloned its own Keystone XL in the U.S and Canada.

It comes in the form of the combination of Enbridge’s Alberta Clipper (Line 67), Flanagan South and Seaway Twin pipelines.

The pipeline system does what Keystone XL and the Keystone Pipeline System at large is designed to do: ship hundreds of thousands of barrels per day of Alberta’s tar sands diluted bitumen (“dilbit”) to both Gulf Coast refineries in Port Arthur, Texas, and the global export market.

Alberta Clipper and Line 67 expansion

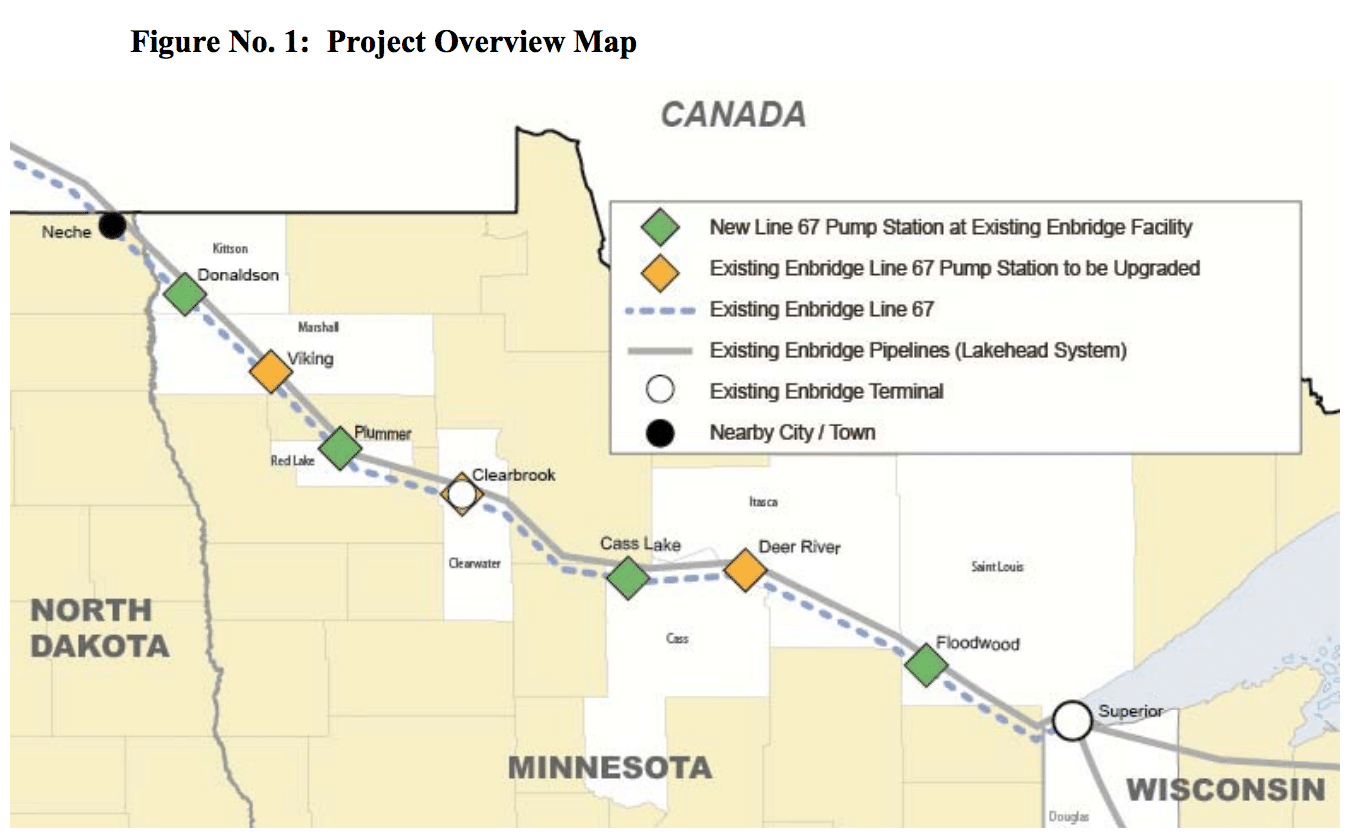

Alberta Clipper was approved by President Barack Obama and the U.S. State Department (legally required because it is a border-crossing pipeline like Keystone XL) in August 2009 during congressional recess. Clipper runs from Alberta to Superior, Wis.

Map Credit: U.S. Department of State

Initially slated to carry 450,000 barrels per day of dilbit to market, Enbridge now seeks an expansion permit from the State Department to carry up to 570,000 barrels per day, with a designed capacity of 800,000 barrels per day. It has dubbed the expansion Line 67.

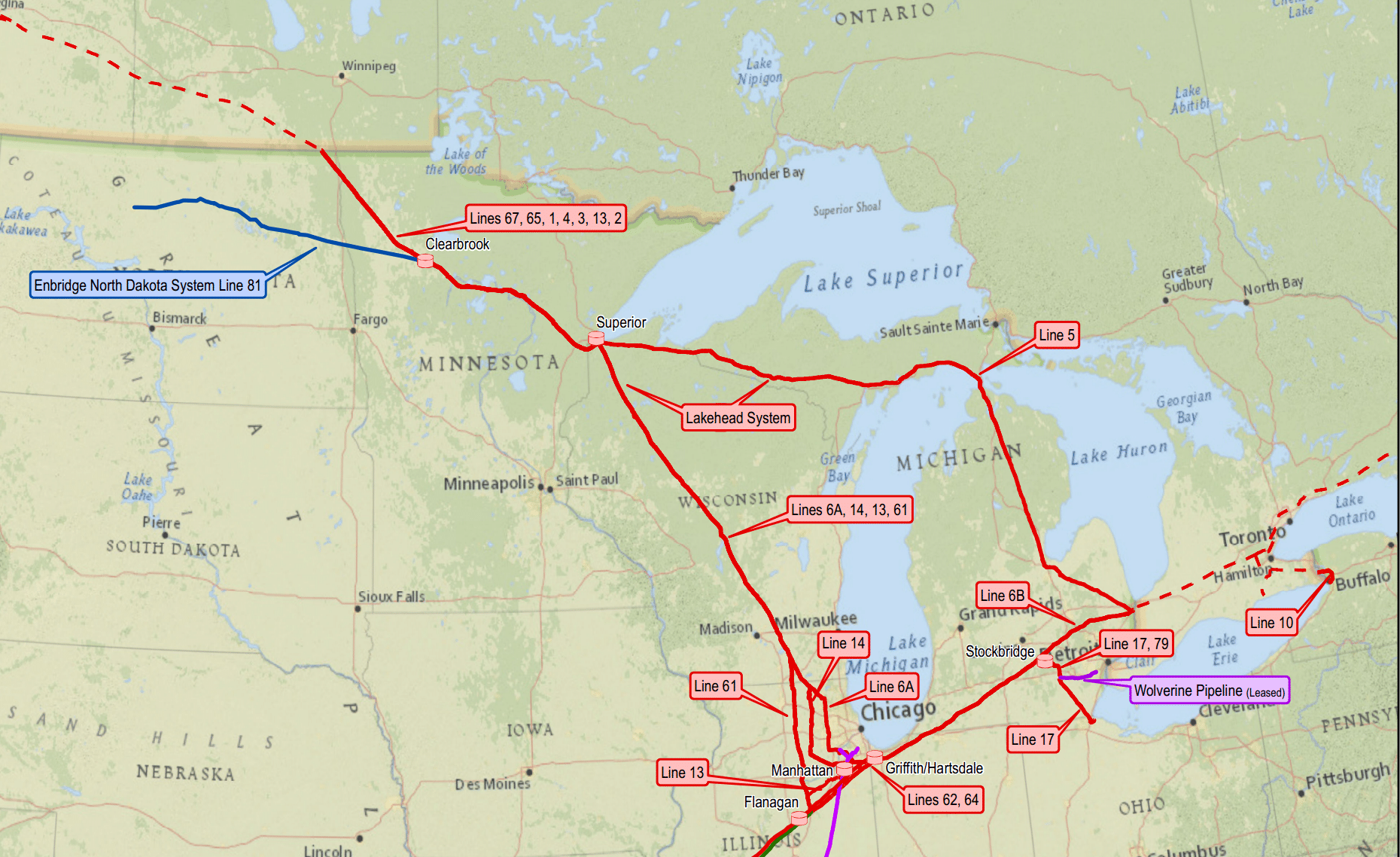

As reported on previously by DeSmogBlog, Line 67 is the key connecter pipeline to Line 6A, which feeds into the BP Whiting refinery located near Chicago, Ill., in Whiting, Ind. BP Whiting — the largest in-land refinery in the U.S. — was recently retooled to refine larger amounts of tar sands under the Whiting Refinery Modernization Project.

Line 67 also connects to Line 61 via a fork in the road of sorts in Wisconsin. From there, it heads to Flanagan, Ill., the namesake of the start of Enbridge’s Flanagan South pipeline.

Enbridge Line 6A; Map Credit: Enbridge

Like Keystone XL, Enbridge’s Line 67 expansion project has faced unexpected delays in its State Department and Obama Administration review process.

Enbridge scheduled Line 67 to go on-line in mid-2014 and reach full-capacity by mid-2015.

But, because of backlash against the proposal from environmentalists and citizens who live along the pipeline expansion’s route, the company does not expect to receive a State Department expansion permit until mid-2015.

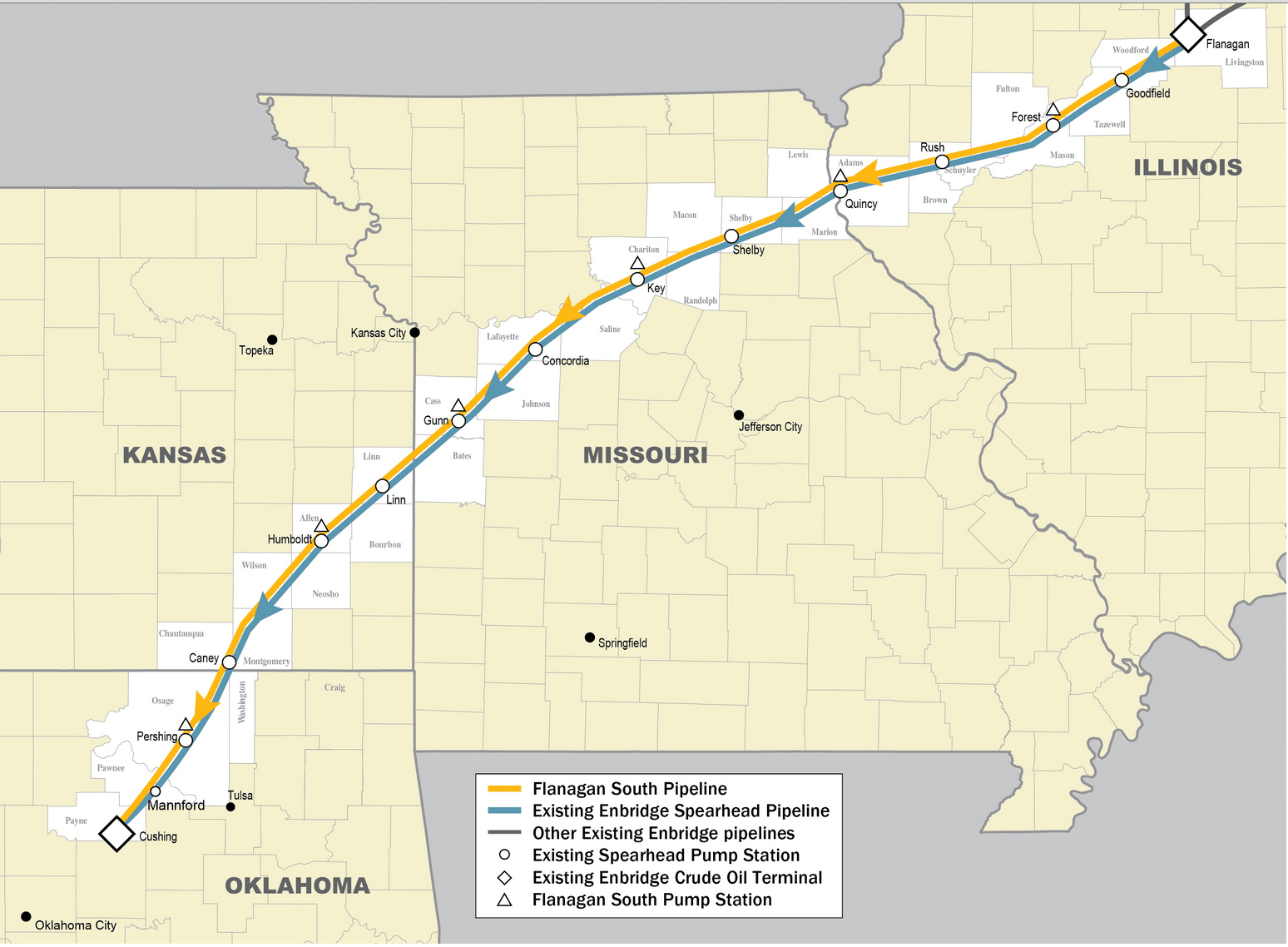

Flanagan South Pipeline

The 600-mile long, 600,000 barrel-per-day Flanagan South is slated to run from Flanagan, south to Cushing, Okla., the “pipeline crossroads of the world.”

Map Credit: Enbridge

Flanagan South also shares a key legal commonality with TransCanada’s Keystone pipeline system.

That is, like Phase II and Phase III of that system — best known to the general public as Keystone XL‘s southern leg and to TransCanada as the Gulf Coast Pipeline Project — it was permitted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers using the controversial Nationwide Permit 12 (NWP 12) process.

As documented here on DeSmogBlog, the southern leg of Keystone XL and Flanagan South both played a central role in separate but related precedent-setting federal-level court cases.

In reviewing the legality of approval via NWP 12 through the lens of “harms,” the courts ruled in both cases that the harms of losing corporate profits for both Enbridge and TransCanada trump the potential harms of ecological damage the pipelines could cause in the future. Climate change went undiscussed in both rulings.

According to a May 2014 company newsletter, Enbridge is “on schedule to put [Flanagan South] in operation later this year.”

“After eight months of construction, we are now in the home stretch for the nearly 600-mile pipeline project,” touts the newsletter. “At the peak of construction, between October 2013 and January 2014, there were on average 3,650 construction workers over the entire route — about 1,600 of those workers from communities located along the pipeline route.”

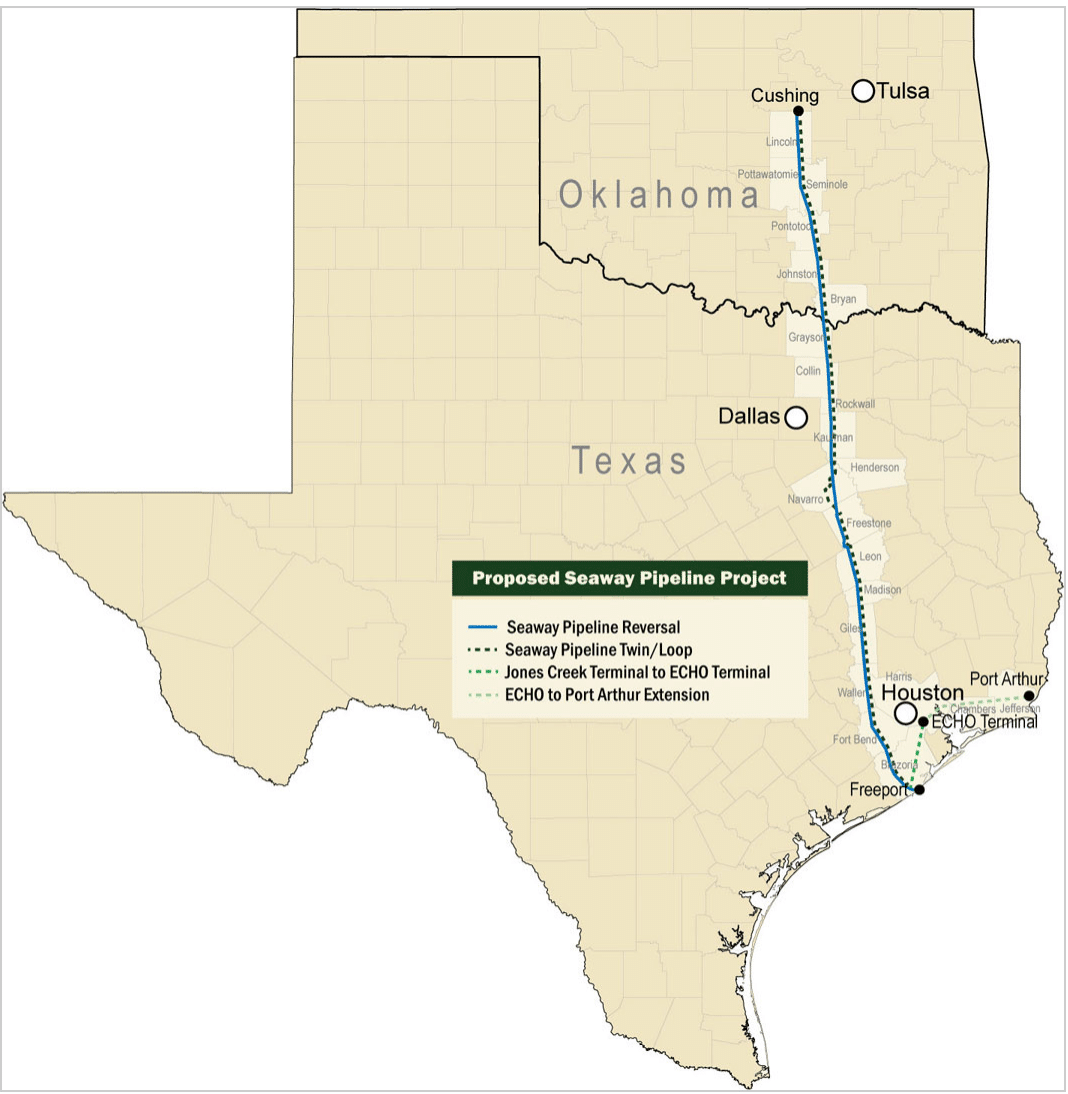

Seaway Pipeline

In a June 16 article titled, “Blame Canada,” Reuters pointed to two new “pipes set to hit U.S. Gulf with heavy crude,” which — as it pertains to Canada — is industry vernacular for tar sands.

Flanagan South was one of the pipelines pointed to in the Reuters piece.

The other is Enbridge’s Seaway Twin pipeline, co-owned on a 50/50 joint venture basis with Enterprise Products Partners. Seaway Twin, like Keystone XL‘s southern leg, runs from Cushing, Okla., to Port Arthur, Texas.

Map Credit: Enbridge & Enterprise Products Partners

As the Reuters article explains, Seaway and Flanagan South are in essence the same pipeline in terms of their interconnectedness.

“Traders say the Seaway Twin has almost enough committed shippers to run at full rates, although it won’t likely run full in the near term until there is increased capacity to bring Canadian crude to the Midwest,” says the article. “That will change in the third quarter, however, when…Flanagan South will connect the company’s main Canadian export pipeline to Cushing.”

Port Arthur, Texas; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

From Port Arthur, the dilbit could be refined or shipped to the global market, though Enbridge told Reuters “virtually” all of it is for U.S. domestic use.

“Texas Bound and Flyin’” and Off to Europe?

On May 5, DeSmogBlog reported that with Keystone XL South opening up for business, dilbit from Cushing, Okla., is “Texas Bound and Flyin’” to the Gulf coast, to borrow the namesake of the song by country singer Jerry Reed.

When Seaway and Flanagan South open for business in the second half of 2014 and with the non-expansion portion of Alberta Clipper already operational, these trend lines will likely continue in the months and years ahead.

And European countries may soon import tar sands at much higher levels from Texas, as well.

In April, Enbridge became the first company to declare publicly that it had obtained a license to re-export dilbit from the United States to the global market.

About two months later on June 5, Reuters reported that the European Union (EU) got rid of the legal requirement to label tar sands as dirtier than other forms of oil. The EU decision came in the aftermath of “years of lobbying from top producer Canada.”

Then just a day later on June 6, The Guardian reported 570,000 barrels of dilbit had reached the shores of Spain, the first shipment to reach Europe.

“While all eyes are on Keystone XL‘s northern leg, Enbridge has sneakily ramrodded in a massive tar sands pipeline system. Like the Keystone Pipeline System, Enbridge’s network moves one of the dirtiest form of energy in the world through sensitive U.S. ecosystems and farmland to the Gulf Coast for export,” Debra Michaud, co-founder of Tar Sands Free Midwest, told DeSmogBlog.

“The environmental movement needs to focus on the entirety of this massive network expansion.”

Photo Credit: Nomad_Soul | Shutterstock

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts