An EPA-approved methane sampler widely used to measure gas leaks from oil and gas operations nationwide can dramatically under-report how much methane is leaking into the atmosphere, a team of researchers reported in a peer-reviewed paper published in March.

The researchers, one of whom first designed the underlying technology used by the sampler, warn that results from improperly calibrated machines could severely understate the amount of methane leaking from the country’s oil and gas wells, pipelines, and other infrastructure.

“It could be a big deal,” study co-author Amy Townsend-Small, a geology professor at the University of Cincinnati, told Inside Climate News, adding that it’s not yet clear how often the machine returned bad results, in part because figuring out whether there’s an error would have required using a different kind of device to independently test gas concentrations at the time levels were originally recorded.

Because of their climate-changing implications, methane leak rates are perhaps the single most consequential issue surrounding the shale gas rush and the push by the Obama administration for a shift from burning coal to burning natural gas for the nation’s electricity supply. Because natural gas is primarily made of methane, an unusually powerful greenhouse gas, if enough methane escapes into the atmosphere, these leaks could potentially make natural gas a worse fuel for the climate than burning coal.

And methane leaks are at their most powerful – 86 times stronger than the same amount of carbon dioxide – in the first two decades or so after they hit the atmosphere. Climate scientists warn that methane leaks risk pushing the climate over an irreversible tipping point where melting permafrost and other self-reinforcing cycles can cause global warming to spiral out of control.

This means that, even though most of the attention from climate scientists is focused on carbon dioxide, figuring out exactly how much methane is leaking from the nation’s oil and gas infrastructure is extraordinarily important.

The oil and gas industry is behind roughly a third of all methane leaks nationwide – more than any other industry, according to the latest EPA data, released April 16. The industry’s emissions from 2013 moved higher than in the previous year even though fewer oil and gas wells were drilled, the EPA noted.

But the issue with the methane sampler – the only commercially-available device approved by the EPA for reporting greenhouse gas emissions that takes instant readings of methane levels – could mean that even more methane is leaking than previously indicated by EPA.

“It’s hard to figure out how widespread this problem could have been since the mistake doesn’t really leave a trace in the records and it’s impossible to know after the measurement has been taken how much, if any, of an underestimate it might be,” Ms. Townsend-Small told DeSmog. “A few recent papers have shown that the methane emissions in the USA and in some individual regions are higher than what the EPA estimates predict, which is what the case would be if the high flow issue is widespread.”

The oil and gas industry is allowed to use the backpack-size Bacharach device, for example, to take readings of methane emissions from gas compressor stations under EPA’s greenhouse gas reporting rules.

“[T]hat data is reported to EPA annually,” explained Touche Howard, who invented the underlying technology used in the Bacharach Hi-Flow Sampler, but was not involved in the development of the Bacharach device itself, “and although it’s not used currently for regulatory purposes the assumption is that it may be used to develop future regulations, so good measurements are important.”

The sampler – the Bacharach Hi-Flow Sampler – costs roughly $20,000, far less than alternative tools available for sale. Inside each Hi-Flow Sampler are two sensors – one designed to kick in when methane levels are above 5 percent, and another more sensitive sensor designed to report levels below 5 percent. The problem, the research team reported, is that under some circumstances, the sampler can fail to shift from its low sensor to high one, giving false low readings even when concentrations reached potentially explosive levels.

For example, the researchers discovered that in methane concentrations as high as 73 percent, two Bacharach Hi-Flow samplers both failed, reporting that levels were between 1 and 6 percent.

When researchers using the instrument are aware of the issue, they can take steps to prevent the Hi-Flow Sampler from failing to switch gears. Properly calibrating the sampler and taking other simple steps can allow researchers to use the Hi-Flow Sampler to obtain accurate results, the researchers concluded.

But because the tool has undergone regulatory approval, changing scientific protocols requires the government to get involved. “One possible solution, Ferrara said, is to get the EPA to pressure Bacharach Inc. to change its manual,” Inside Climate News reported. “But because the Bacharach sampler is an EPA-approved device, it may require complex regulatory action, he said.”

While the Sampler can give low-ball results, it is unlikely that it would give erroneously high results. “The authors demonstrate rather convincingly that it is easy to use this instrument in such a way as to get estimates that are incorrect, with the error always one of underestimating methane emissions, and potentially by a lot,” Prof. Robert Howarth told Inside Climate News. “Since this instrument is widely used to meet EPA emissions requirements, this does indeed call into question those data.”

A broad swath of data could be affected. Methane measurements reported by the oil and gas industry, EPA data that is based on that industry-reported data, and independent academic research into methane leaks may all understate the true leakage rate as a result. The sampler is generally used to take spot samples on the ground – meaning that it’s possible that the malfunctions could help explain why aerial sampling above oil and gas sites show far higher methane levels than the levels reported at ground level would predict.

Correcting for a flawed sampler’s incorrect reading after the fact is no simple task, Howard told DeSmog. “First, you can’t tell just by looking at the data if an error has occurred – that has to be determined by a simultaneous comparison with an independent measurement, or by noticing aberrant behavior of the instrument while the measurement is being made, or by analyzing data trends,” he said. “More importantly, once the error occurs, you don’t know how bad the measurement is, because the emission rate you’re measuring might be just a little bit above the low range threshold (so, for instance, causing a 20% error), or in the extreme, being past the range of the instrument’s high range, causing error of greater than a factor of 50. “

Howard said that by calling attention to the issue, the researchers hoped to prevent scientists from mis-using the device in future research. “We don’t want to be accusatory,” he told Inside Climate News. “Our goal is to get people to get the best results possible.”

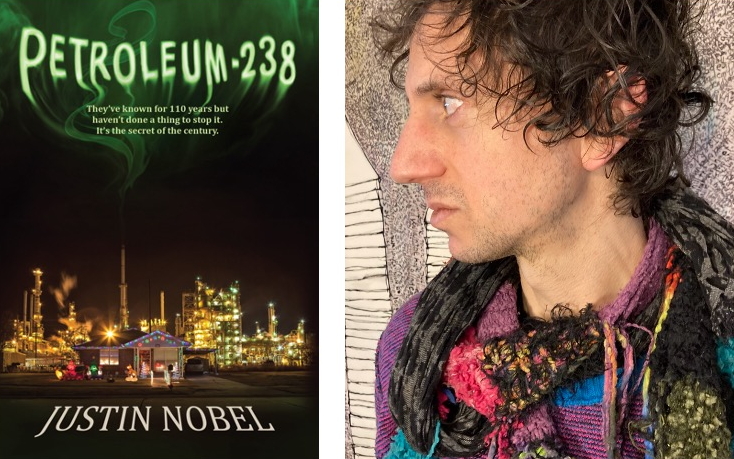

Photo Credit: Closeup Morning Sunrise at Petroleum Refinery, via Shutterstock

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts