There are solar battles blazing all across the west right now, as utilities anchored to fossil fuel power plants strain to avoid the inevitable spread of solar across their areas of operation.

Not a month goes by without a story of some assault on solar-friendly policies by utilities, or by the Utility Commissions that are often in their pocket.

During the holidays at the end of 2015, it was Nevada’s utter dismembering of its net metering policy. Nevada is—or was—one of 42 states that offered net metering, a program through which customers with solar arrays are compensated for the energy they produce on their rooftops or in small installations connected to the electric grid.

NV Energy Inc. unleashed this full frontal attack on the program that—in one quick vote of three unelected commissioners—pulled the rug out from under 17,000 solar customers and eviscerated at least 8,000 solar jobs. And the Public Utilities Commission of Nevada (PUCN) was happy to oblige.

Nevada has the highest number of solar jobs per capita in the United States, but for how long?

As Nevada’s PUCN invited this “solar black hole” over one of the nation’s sunniest states, many pointed out how NV Energy fought tooth and nail against the successful net metering plan, and ultimately secured its demise.

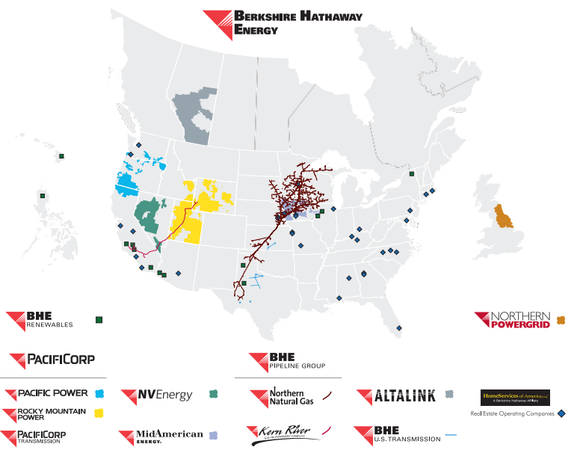

NV Energy, the state’s largest utility, is a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy. This net metering battle was high profile.

Many have pitched it as a Buffett versus Musk showdown, as NV Energy’s demands would prove to cripple Solar City’s business in the state, which was dependent on a consistent net metering program.

But this is far from the only move Buffett is making against solar. In Utah, Rocky Mountain Power—a division of PacifiCorp, which is a fully-owned subsidiary of… you guessed it… Berkshire Hathaway Energy—proposed a charge for solar net metering customers similar to that which passed in Nevada. The Utah Public Service Commission voted that proposal down.

There’s a decent bit of spotlight on the net metering battles, but Buffett’s holdings are actively engaged in a quieter war on another solar front.

Yet just last year, Berkshire Hathaway Energy signed President Obama’s Climate Commitment, pledging to “lead on climate action.”

PURPA: “The Backdoor Solar Answer Out West”

At issue is a relatively little known federal statute that has been a huge boon to solar development around the country, and especially in the big Western states. It’s called PURPA, or the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act, and it basically ensures that renewable generating facilities of a certain size (up to 80 megawatts; the projects that fit these conditions are called Qualifying Facilities, or QFs) can sell their power to utilities for a certain fair price. That price is called the “avoided cost rate” in utility-speak, and is basically what the utility would have had to pay for the same amount of power from another source or to generate it itself.

Problem is, utilities would rather generate the power themselves because they get a better return on those power plants that they own. Utilities don’t want to be told they have to enter into long term contracts with outside developers, even if the cost of the power is the same as what they would pay to generate it themselves.

But that’s what PURPA does. By mandating that the utilities approve these long term contracts with medium-scale solar and wind projects, the Act has historically allowed a renewable energy developer to lock in a 15 to 20-year contract, providing the stability that secures the financing.

This security has helped hundreds of solar and wind projects plug into the grid. PURPA helped usher in the mini wind power boom in the early 1980s and, over the past decade, it has helped bring thousands of megawatts of wind online all across the west. Lately, solar is lining up in the queue to plug into PURPA contracts.

The Union of Concerned Scientists has gone so far as to call PURPA “the most effective single measure in promoting renewable energy,” and a UBS Securities report recently called PURPA, “The Backdoor Solar Answer Out West.”

Look no further than Utah: a state that is dominated by coal-fired generation and that has no renewable portfolio standard. And a state where one company alone, SunEdison, has quickly built over 700 megawatts of solar in a few short years.

And that’s why Warren Buffett’s utilities want to crush it. Berkshire Hathaway Energy’s holdings are still intractably dependent on coal—relying on it for well over half of electricity generation in its four major regional utilities. And the fact that Buffett’s BNSF Railways hauls a whole lot of coal is a subject often covered here on DeSmogBlog.

Credit: Berkshire Hathaway Energy

The various Berkshire Hathaway subsidiaries are executing a multipronged PURPA attack targetting the state level utility commissions, while also lobbying for federal reform on Capitol Hill. Here’s the current state of play.

Idaho

Last August, PacifiCorp, operating in Idaho as Rocky Mountain Power, started the state-level siege on PURPA. Joining forces with Idaho Power, the utilities argued to the Public Utility Commission that too many solar and wind projects were seeking grid connection through PURPA. To bolster its argument, PacifiCorp claimed that with existing and proposed PURPA contracts, enough power would be generated to supply 108-percent of the utility’s average load. (As if that were a bad thing.)

The Commission basically agreed with the companies, granting the request to reduce the length of contracts to just two years. “The utilities all have ample amounts of PURPA on their systems and additional renewable generation is in the queue,” the PUC said.

The policy change will have an immediate impact on solar development in the state, as it forces big developers like SunEdison to pull out. “We’d like to invest further in Idaho, but we’re not going to be able to build a project on a two-year contract,” said Ben Fairbanks, SunEdison’s development manager for the Northwest.

Oregon

Across the border in Oregon, Pacific Power, another subsidiary of PacifiCorp, asked the Public Utility Commission to shorten PURPA contract lengths from fifteen to three years.

“PacifiCorp, in particular, has a giant fossil fuel fleet and they’ve shown very little interest in developing a renewable energy portfolio,” said Travis Ritchie, an attorney with the Sierra Club.

David Brown, owner of Obsidian Renewables in Lake Oswego, described the chilling effect that the shortened term has on developers, said: “Nobody is going to loan you money on a 15-year loan if you only have a three-year purchase agreement. I think it would be an end to PURPA projects.”

A final order from the Oregon Public Utility Commission is expected in March.

Wyoming

In its filings to the Commission, Rocky Mountain Power said it is facing 713 megawatts in proposed PURPA projects, in addition to 413 megawatts in existing PURPA development, which together would account for a full 96-percent of its average load. This in a state where traditionally 90-percent of electricity generation has been coal-fired.

The Wyoming PSC will hold a hearing in March, and a decision is expected soon thereafter.

Utah

Rocky Mountain Power made the very same request last year in Utah: asking that the purchase agreements from PURPA qualified facilities be shortened from twenty years to just three years.

The Utah Public Service Commission, however, offered a solar-friendly compromise, shortening the term to 15 years, a move that was generally applauded by the solar industry.

In its decision, the Commission stated that “a term of 3-5yrs would not sufficiently compensate a QF (qualifying facility) for generation.“

Federal Showdown

The patchwork of state rulings might well be leading to some federal intervention. No surprise, then, that Berkshire Hathaway has been actively engaged in lobbying for PURPA reform in Washington D.C.

Back in April and May 2015, there was a flurry of legislation introduced, with at least five Senate bills proposed that dealt with PURPA in some shape or form.

As the Senate was debating Senator Murkowski’s broad energy bill, Berkshire Hathaway Energy lobbyist Jonathan Weisgall testified before a hearing that many Western utilities should be exempt from their requirements to buy power from a PURPA-qualified facility.

Senator Maria Cantwell of Washington, the top ranking Democrat in the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, noted the many coal holdings in the Berkshire Hathaway portfolio—from coal generation power plants to BNSF Railway, which makes a good deal of its business now from coal shipments—and essentially called the company out for lobbying to stifle competition.

She asked: “Isn’t it the case that obviously getting rid of this PURPA requirement would just greatly benefit the company financially on your profit margin by reducing competition for central station generation?”

Not long after, Weisgall was back at the Capitol, this time in the lower chamber, making similar testimony to the House.

The current version of Senator Murkowski’s bill, however, doesn’t include any significant changes to PURPA.

Which isn’t to say that Berkshire Hathaway’s interests have been ignored by leaders in Congress. Senator Murkowski and her counterparts in the House — Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Fred Upton and House Energy and Power Subcommittee Chairman Ed Whitfield — have requested that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) conduct an official technical conference to review PURPA. This week, FERC agreed, and the conference will be held on June 29.

Blog image credit: Snake River Alliance

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts