More than a decade ago, Bill Wehrum, then acting assistant administrator for air and radiation at the US Environmental Protection Agency, successfully fought to deny the state of California the right to set its own standards on greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles.

He is now back in the same position at Trump’s EPA, and hoping to try once again to kill the California waiver.

That first denial in 2007 was a stunning departure from precedent. For more than 30 years since the Clean Air Act was passed, California had received a waiver to set more stringent pollution standards than the EPA’s national targets every time it made the request from the agency. That changed in December 2007, when then-EPA Administrator Stephen Johnson denied the state’s request. Johnson’s decision was informed by input from Wehrum, who ran the EPA’s clean air division at the time and who later affirmed publicly that he had argued against granting the waiver.

Why does this matter now? Because Wehrum is again the EPA’s air chief, and he is currently running the agency’s midterm review of auto emissions standards—a review that necessarily touches upon California’s waivers. And his only public comments on this forthcoming decision left the door open to another denial of the waiver.

Wehrum is a key figure in deciding whether to roll back the national Obama-era emissions standards for vehicles, and whether to then rescind (or refuse to grant anew) a waiver that California will rely on to preserve the more stringent existing standards.

In short: Wehrum played a large role in the only waiver denial in the EPA’s history, and he is now in the position to do it again.

Before digging deeper into Wehrum’s history as a lawyer for industry and for issuing dozens of unlawful rules while at the EPA, let’s take a quick look at why these California waivers are such a big deal.

What is the California waiver?

Let’s start with some quick history: when Congress passed the amended Clean Air Act in 1970, it included a unique provision for the state of California to essentially write its own standards for tailpipe emissions. Through the law, California could apply for a waiver from the EPA when it wished to enact more stringent rules than the agency; then, if they were “at least as protective of public health and welfare” as the EPA’s, the administrator would be compelled to grant the waiver. Though California alone could request such a waiver, other states are allowed to adopt California’s standards. Currently, 13 other states and the District of Columbia have adopted the stricter California standards. (Today, the so-called “Section 177 states,” named after the pertinent section in the Clean Air Act of 1970, are: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.)

For more than three decades, the EPA granted each and every one of California’s waiver requests. Then, in 2006, California requested a waiver to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles. After two public hearings and notice and comment rulemaking process, the EPA denied the waiver.

California sued, and the case was still pending when the Obama administration took over in 2009. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court decided in 2007 that the EPA was required to regulate greenhouse gas emissions if they were found to endanger public health and welfare, and such a determination was then made by the agency in 2009. As part of the auto industry bailout in 2009 (and then subsequent talks in 2011), the Obama White House brought together automakers, the Department of Transportation, the EPA, and California air pollution authorities and hammered out a unified national set of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (or CAFE) standards and tailpipe emissions standards that include greenhouse gas regulations. California was granted the waiver, but in the interest of having uniform standards nationwide (a critical ask of Detroit), the state and federal agencies agreed to the negotiated deal.

The agreed upon standards were set through 2025, however, parties agreed that before the end of 2017, agencies would conduct a “midterm review” of the feasibility (technologically and economically) of achieving the targets for the later years, from 2022-2025. Obama administration agencies conducted these reviews and essentially declared that the targets were fine.

Then the Trump team took over. The nuances of administrative law allowed Trump’s DOT and EPA to throw the Obama reviews aside and conduct their own midterm reviews, which they are doing now. The DOT is expected to release its finding on March 31, with the EPA’s coming the next day.

This is where California comes back into the picture. If the Trump EPA were to decide that they want to loosen the standards — and make no mistake, car companies through the powerful Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers have been asking them to do just that) — California has said consistently that it has no interest in walking back its regulations.

So the auto industry would be looking at two sets of standards: the EPA’s, and California’s, which having been adopted by all of the other Section 177 states, would cover more than one-third of auto sales. Nobody wants two regulatory regimes, especially Detroit.

It has been reported that Wehrum and EPA staff are in discussions with California regulators on the subject of the midterm review, in order to preserve a nationwide set of tailpipe standards.

The Waiver Denial

Back up for a moment to the 2007 waiver denial. In his letter to Governor Schwarzenegger denying the request, Administrator Johnson wrote that, “In light of the global nature of the problem of climate change, I have found that California does not have a ‘need to meet compelling and extraordinary conditions.’” In other words: California does not suffer uniquely from the impacts of climate change—these “compelling and extraordinary conditions” being a condition written into the Clean Air Act’s language establishing the state’s right to a waiver.

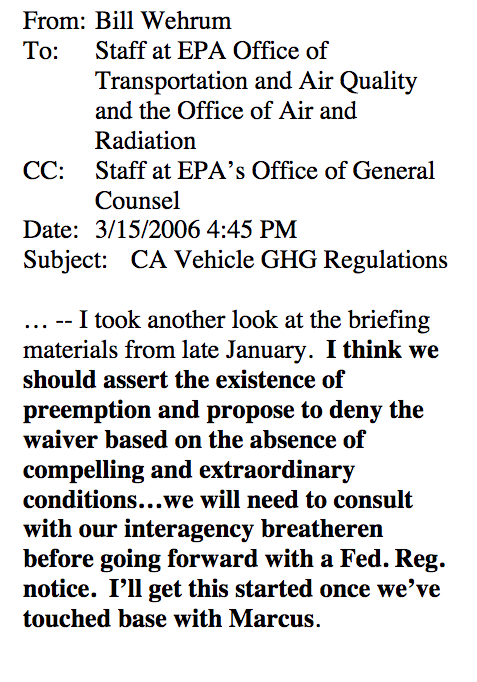

Johnson’s explanation echoed language used by his acting assistant administrator in the Office of Air and Radiation, Bill Wehrum, in an internal email to EPA staff.

Email from Bill Wehrum to EPA staff justifying the EPA‘s unprecendented denial of Californias Clean Air Act waiver request in 2006. Credit: Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works.

“I think we should assert the existence of preemption and propose to deny the waiver based on the absence of compelling and extraordinary conditions,” Wehrum wrote. Ultimately, that’s exactly what the EPA did.

At the Washington Auto Show’s Public Policy Day in January, DeSmog submitted a question during a Q&A session with Wehrum, asking whether the agency was considering revoking or not renewing California’s waiver, pending the outcome of the agency’s midterm review of emissions standards.

His response to this—and other related queries—were noncommittal, and could be read as contradictory.

The EPA has “no interest whatsoever in withdrawing CA‘s authority to regulate,” said Wehrum.

Then he said, ““What I want is one national program. If we can all agree on what needs to be done, then we can all go forward.”

“One national program is important to us,” he emphasized.

EPA‘s top air pollution guy alluding to the possibility that the federal government might deny California’s vehicle emissions waiver.

The waiver lets CA set stricter standards than federal. Means automakers manufacture cars that meet stricter standards bc CA is a huge market. https://t.co/9KVBFYOXEA

— Natasha Geiling (@ngeiling) January 25, 2018

Who is Bill Wehrum?

If there is one main theme that defines Wehrum’s career within the EPA and in private practice, it’s been a consistent effort to weaken and undermine public health and environmental protections established in the Clean Air Act. Let’s unpack a few elements that stand out in his career.

Wehrum has had two very rocky nomination processes for the same EPA job, only one resulting in confirmation.

In November 2017, Wehrum was confirmed to serve as Assistant Administrator for EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation (OAR) by a tight 49-47 Senate vote (with two Democrats and two Republicans abstaining). Notably, two Democratic Senators who voted for EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt voted against Wehrum. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia and Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota both expressed concerns about his record on issues of public health.

During his committee hearing, Wehrum also questioned the scientific consensus on climate change, calling it an “open question” as to whether humans were a major driver.

To which Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon said in response, “You’ve got to be kidding me with this nominee.”

You’ve got to be kidding me with this nominee. pic.twitter.com/85w8Ru2618

— Senator Jeff Merkley (@SenJeffMerkley) October 4, 2017

Despite Democrats’ objections, Wehrum was confirmed and now leads the office responsible for policing the Clean Air Act.

Ten years earlier, he was blocked from attaining that same position. In the Bush administration’s EPA, Wehrum rose from a counsel in the air office to eventually serve as Acting Assistant Administrator in OAR, but the White House withdrew his name to fill the role permanently after Senator Barbara Boxer of California had put a hold on his nomination.

At the time, Boxer had said Wehrum’s record “demonstrates a pattern of discounting health impacts, ignoring scientific findings and substituting industry positions for the clear intent of Congress.”

Senator Jim Jeffords, an Independent from Vermont, also opposed Wehrum’s original nomination, saying that “[h]is disdain for the Clean Air Act is alarming.”

Wehrum made an “astonishing” number of unlawful decisions in his first EPA stint

During Wehrum’s time in Bush’s EPA air office, courts repeatedly found the agency to be acting in violation of the Clean Air Act. According to NRDC’s John Walke, “the EPA’s air program lost an astonishing number of Clean Air Act cases during Wehrum’s tenure.”

The agency’s own data, cited by Walke, shows that “public health and environmental groups prevailed in court against Bush EPA air pollution rules 27 times in those 7 years.” In other words, Wehrum oversaw or helped develop illegal rules that were found unlawful 27 times.

Walke adds, “Under Wehrum’s leadership, the Bush air program did not just lose clean air lawsuits frequently; it lost them badly, by violating the plain language of the law egregiously, again and again.”

This record of unlawful action at EPA surfaced again in his 2017 confirmation hearings, when Senator Tom Carper argued:

“I have said this before, and I’ll say it again because it makes Mr. Wehrum’s priorities clear: Our courts have overturned regulations that Mr. Wehrum helped craft while at the EPA a staggering 27 times. That’s 27 times that the courts determined that the rules that Mr. Wehrum put in place did not follow the law or did not adequately protect public safety.”

After representing polluting industries, Wehrum lifted their language “verbatim” at EPA

Before and after working in the Bush EPA, Wehrum worked as a corporate attorney representing a number of coal, oil, gas and chemical companies, as well as groups like the American Petroleum Institute (API), the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), and the Utility Air Regulatory Group (UARG). Industry clients have also included Kinder Morgan, Georgia-Pacific, and Koch Industries. He frequently sued the EPA on behalf of these companies and trade groups, fighting a number of Clean Air Act related regulations. According to NRDC, Wehrum sued the EPA 34 times, all but two of those lawsuits coming after his nomination to serve as air chief has been withdrawn.

Perhaps most troubling is the evidence of how Wehrum’s industry ties bled into his work within the EPA. In 2004, Wehrum was at the center of a controversy regarding mercury emissions. The Bush EPA proposed rules for regulation of airborne emissions of the toxic pollutant, and the agency’s language was copied-and-pasted from a memo sent to EPA by a law firm representing electric utilities.

“A side-by-side comparison of one of the three proposed rules and the memorandums prepared by Latham & Watkins…shows that at least a dozen paragraphs were lifted, sometimes verbatim, from the industry suggestions,” the Washington Post reported.

The law firm, Latham & Watkins, was Wehrum’s former employer. Though the EPA dismissed the incident as an agency mixup, Wehrum later admitted “it was he who forwarded the language to EPA subordinates writing the rule.”

As the Los Angeles Times reported, “The agency’s inspector general denounced the effort, saying it relied on industry input over science.”

Back to the present moment, the concern is that Wehrum will again rely on industry input over science and the exhaustive research performed by EPA staff. Since Trump won the election the Auto Alliance has been lobbying consistently for the administration to ease auto standards, even writing in a February 2017 letter to EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt that the agency’s decision on tailpipe emissions is “the single most important decision the E.P.A. has made in recent history.”

If the EPA does decide through its midterm review to weaken emissions standards, California still has its waiver to preserve tougher standards. Wehrum played a key role in the EPA‘s only waiver denial in the history of the Clean Air Act—a decision that was never affirmed by the courts. Over the next two months, Wehrum will be forced to decide whether to preserve the state’s right to restrict emissions, or to test in courts whether the EPA can deny California’s explicitly granted waiver.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts