As demand for coal in the United States has cooled off in recent years, coal mining companies have been scrambling to deliver their dirty loads to customers abroad. But what does this mean for communities along the transportation routes, particularly at the ports and export terminals where the coal is offloaded from trains and onto boats?

The U.S. EPA, for one, is warning of the potential for “significant impacts to public health” in one such port town.

Coal exports have more than doubled over the past six years, and are at their highest levels in over two decades. According to an Associated Press evaluation of Energy Information Agency coal data, more than 107 million tons of coal were exported in 2011.

But that’s a small drop in the bucket (or lump in the stocking? sorry, couldn’t resist) of what coal companies hope to export in the very near future. (Farron Cousins covered the coal export trend here on DeSmogBlog earlier this year.)

Nowhere is the push to export coal being felt more than in the Pacific Northwest, where there are currently plans to ship more than 100 million tons each year, according to the Sightline Institute.

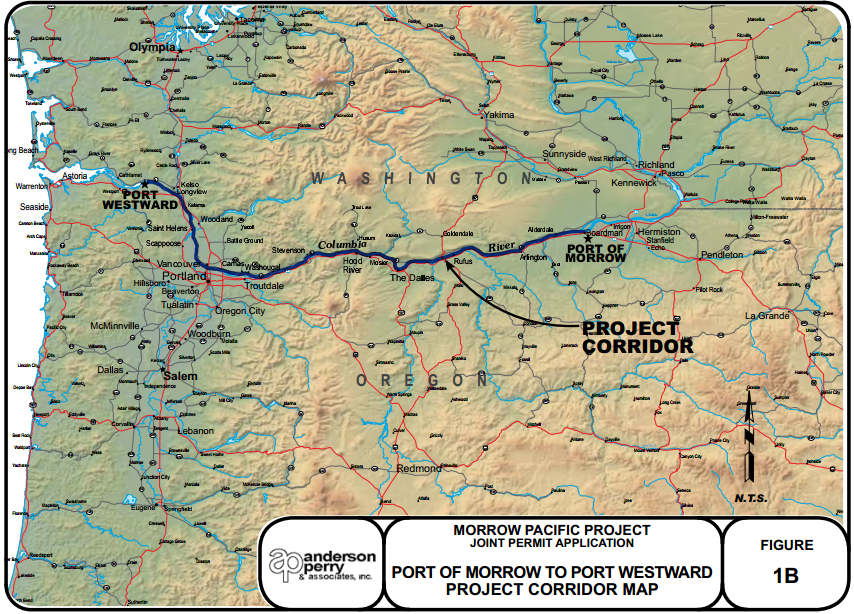

Of course, all of this coal would have to actually get from land to sea, and so companies are working to open up export terminals throughout the Pacific Northwest. One such proposal is for the town of Boardman, Oregon, in a facility formerly called the Port of Morrow. (I’m working on a more comprehensive post about the overall state of coal exports, coal trains, and the potential export terminals throughout the country, especially in the Northwest, so stay tuned for that.)

The company behind the Boardman terminal plans is Coyote Island Terminal LLC, a subsidiary of Ambre Energy, and Australian coal and oil shale company that is one of the major players in the U.S. coal export game. In order to open up the Boardman port, Ambre needs approval of the Army Corps of Engineers, which is currently reviewing the application. Here’s how the project is described in the Army Corps’ Public Notice (PDF)

The proposed project involves construction of a new transloading facility for bringing coal in from Montana and Wyoming by rail and transferring it to barges on the Columbia River at the Port of Morrow…

The coal would be shipped down the Columbia to Port Westward and loaded onto ocean-going “Panamax” vessels to be shipped to Asia. Best management practices would be used throughout the transportation of the coal to contain coal dust, including enclosed warehouses, barges, conveyors, and loading equipment. Initially, approximately 3.85 million tons of coal would be shipped through the facility to Asia each year. At maximum capacity, the facility would be able to handle 8.8 million tons. That would translate to approximately 5 trains to Port of Morrow, 5.5 loaded barge tows from Port of Morrow to Port Westward, and 1 Panamax ship to Asia per week initially, increasing to 11 trains, 12 loaded barge tows, and 3 Panamax ships per week at full build out.

So, in short: in Boardman, coal would be offloaded from trains onto barges in the Columbia River, where it would float down to Port Westward, Oregon (roughly 30 miles north of Portland), where it would be loaded onto big ocean vessels for shipment to Asia.

Some residents of Boardman, with a population of about 3,000, seem welcome to the proposal. A New York Times article from a couple of weeks back quotes a worker from a hay fumigation warehouse that would be just a few hundred feet from the coal facility, saying, “I don’t think there will be any environmental impact anyway.”

The EPA isn’t so sure of that.

On April 5, the EPA submitted public comments (PDF) about the Boardman proposal under the National Environmental Protection Act and the Clean Air Act, and some red flags were raised.

The EPA raised concerns about a number of issues, including impacts on listed species, critical habitats, and aquatic resources, as well as the project’s potential contributions to “cumulatively significant impacts” like climate change and the drift of particulates, mercury, and ozone from Asia to the United States.

But most alarming are the agency’s concerns about public health. From their comments:

Transporting and transloading up to 8.8 million tons of coal with eleven trains, twelve loaded barge tows, and two Panamax ships per week has the potential to significantly impact human health and the environment. Two of our primary preliminary concerns relate to the potential for adverse effects from project-related coal dust and diesel pollution. Coal dust is a human health concern because it can cause pneumoconiosis, bronchitis, and emphysema. Coal dust is an environmental concern because it may settle on water, soil, or vegetation and impair biological processes such as photosynthesis. In addition, coal dust has been shown to cause tumors in experimental animals. We are similarly concerned about diesel emissions because they can cause lung damage, aggravate existing respiratory disease such as asthma and are thought to be a human carcinogen. Diesel emissions have a high potential to impact people who are sensitive to the health effects of fine particles (e.g. children, the elderly, and those with existing heart of lung disease, asthma or other respiratory problems).

The EPA’s role in the Corps’ permitting process, however, is only advisory, so the Corps can choose to accept or reject the agency’s recommendation.

If you would like to submit a public comment about the proposed project, send an email or letter to this address:

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Mr. Steve Gagnon; [email protected]

PO Box 2946

Portland, OR 97208-2946

You must reference this Corps number: NWP-2012-56

The public comment period ends May 5, 2012.

More details are available in the Army Corps’ Public Notice (PDF).

Photo: Paul K. Anderson, via CoalTrainFacts.org

Map: US Army Corps of Engineers (PDF)

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts