Update 7/3: On Monday, June 2, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration of the Department of Transportation announced that Enbridge would be fined $3.7 million for 24 safety violations associated with the Kalamazoo River oil spill, including the damning charge that Enbridge had identified corrosion on the faulty pipeline more than six years before it failed. The $3.7 million claim is a record civil penalty, and Enbridge has 30 days to decide whether to accept the decision.

Original post: By now, hopefully you’ve at least heard of the Kalamazoo River oil spill. Though it didn’t gain nearly the press attention as the Deepwater Horizon disaster, it was a massive spill that is still plaguing the local communiy nearly two years after the pipeline burst.

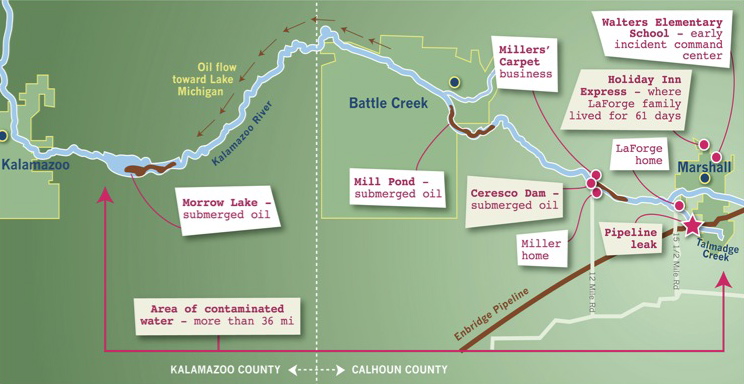

Some background: On a midsummer evening in July of 2010, heavy crude started gushing from a 30-inch pipeline into Talmadge Creek, near Marshall, Michigan. By the next morning, heavy globs of oil soon were coating the Kalamazoo River, into which the Talmadge flows, and the stench of petroleum filled the air.

Enbridge, the Canadian company that owns and operates the ruptured pipeline 6B, made a lot of mistakes in the hours after the first gallons spilled. The disaster didn’t have to be so bad. Records of the official responses showed, for instance, that the company didn’t send someone to the site until the next morning. And that the Enbridge pipeline controllers increased pressure to the line, on a hunch that the funky signals they were getting was from a bubble, and not a spill.

When all was said and done, an estimated 1 million gallons of tar sands crude had leaked into the Kalamazoo River — ranked by the EPA as the largest spill in Midwestern history — with some oil flowing a full 40 miles down the river towards Lake Michigan.

Though the company that owns the pipeline, Enbridge, tried to deny it, the oil was soon revealed to be diluted bitumen (or DilBit), a form of tar sands crude that is thick and abrasive and can only be pumped through pipelines at enormously high pressure. DitBit is also, it turns out, much harder to clean up than regular old dirty crude. All told, Enbridge’s 6B spill was one of the worst oil spills

InsideClimate News has just released an incredibly comprehensive roundup and in-depth report of the disaster in it’s entirely – from the first signs of trouble along the pipeline’s monitoring systems to the messy aftermath that continues to cause the local community grief.

Reporters Elizabeth McGowan and Lisa Song, who have been on top of this story since the beginning, traveling multiples times each up to Michigan for on the ground reporting, have done an incredible job of laying bare the facts in an engaging narrative. The investigation is part narrative, part explainer. A narrative of what happens to two local families and the entire community when an oil disaster strikes. And an explainer of how diluted bitumen (DilBit), the form that tar sands crude take to travel through pipelines, is a hell of a lot harder to clean up than regular old crude.

While there have been some great pieces of individual reporting on this disaster (think of Ted Genoway’s amazing Whistleblower series for OnEarth), McGowan and Song start at the top and walk us through every turn in this tragic tale, complete with plain language explainers and maps and plenty of facts and figures and pieces of original reporting. Here’s how they summarize the incident, for instance:

The spill happened in Marshall, a community of 7,400 in southwestern Michigan. At least 1 million gallons of oil blackened more than two miles of Talmadge Creek and almost 36 miles of the Kalamazoo River, and oil is still showing up 23 months later, as the cleanup continues. About 150 families have been permanently relocated and most of the tainted stretch of river between Marshall and Kalamazoo remained closed to the public until June 21.

In a blow-by-blow account of the discovery of the spill (or, rather, of the spill making itself impossible to continue to ignore), McGowan and Song let the facts incriminate.

Because the NRC line was busy, Enbridge didn’t get through until 1:33 p.m.—almost two hours after it had confirmed the spill and more than three hours after Enbridge workers urged the LaForges to leave their home. The company reported a spill of 819,000 gallons of oil.

Three minutes after Enbridge finished talking with the NRC, the center had contacted 16 agencies.

By this time, the same oily muck that had darkened the LaForges carefully tended lawn was sloshing over the banks of Talmadge Creek and coating tree trunks, flowers and soil along the Kalamazoo River. Jay Wesley, a fisheries specialist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, was already on the scene, trudging along the floodplain and collecting oil-coated muskrats and turtles in cardboard boxes and plastic bins.

Everything reeked of petroleum. Residents were on edge.

Why not load that onto your Kindle for some holiday weekend reading? You can check out “The DilBit Disaster: Inside the biggest oil spill you’ve never heard of” in three-parts, starting here, or you can download the entire thing as an e-book.

Map: Catherine Mann for InsideClimate News

Photo: National Transportation Safety Board

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts