This post is part of DeSmog’s investigative series Cry Wolf.

Alberta’s threatened caribou herds will stand a significantly better chance of surviving the province’s development of the Tar Sands, according to a group of scientists, if the oil and gas industry is willing to spare 1 percent of its potential development profits to make it happen.

According to a recent study from the University of Alberta’s Richard Schneider, 50 percent of the caribou habitat threatened by Tar Sands development could be easily preserved if only the industry and government would be more strategic in their land use planning. But ‘strategy’ has had little to do with the way the Tar Sands region has been managed, according to Schneider, who suggests that caribou have become an unintended victim of the government’s thoughtless industrial leasing program.

The effort to recover caribou largely relies on securing critical habitat for the species. But habitat has proven difficult to conserve in an area like Fort McMurray where the government has leased the majority of the land to individual companies without any longterm land use strategy.

To understand why caribou recovery is so difficult and why industry is so resistant to habitat protection (see our extensive coverage of this problem here), you have to understand the way oil and gas leases are awarded in Alberta, Schneider told DeSmogBlog.

“A piece of land is put forward or is nominated by industry for exploitation…and anyone can bid on it. The companies pay money to the government – quite a lot – and they now have the rights to exploit oil and gas resources in the area. But these blocks are small. If you looked at the lease map in the Fort McMurray area, it looks like a quilt. There are many, many small companies that only have leases for a few townships. The problem becomes, how do we have any sort of coordinated action?”

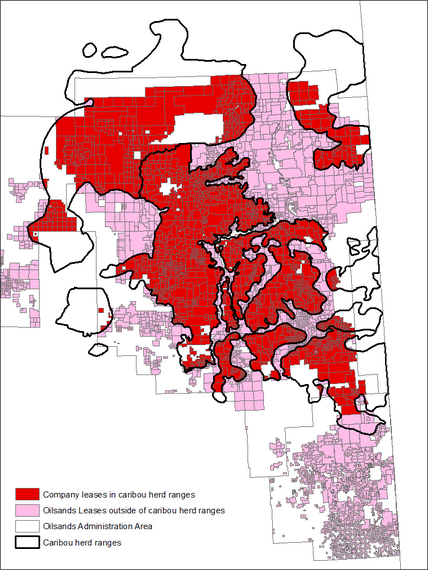

As Global Forest Watch Canada has recently demonstrated with their digitized maps of caribou habitat and Tar Sands overlap, sprawling industrial development has nearly blanketed the entirety of caribou habitat in the region. These new visual resources make it easier to comprehend the quilted patchwork of land leases across the area that Schneider considers problematic. (More maps below).

What makes the leasing system a problem, says Schneider, is that the government forces companies to commence operations on that land whether it is economically viable or not. And for Schneider, much of that forced development is not beneficial, to the company or to the land, even though the government actively orchestrates it.

Much of the leased area holds low-value oil reserves, sometimes not worth the company’s time, “yet government requires [companies] to act on leases in 5 years,” he said. If a company fails to act on a lease within the 5 year period they risk loosing their right to develop the land.

The government is enforcing the mismanagement of the resource, says Schneider, all because of the plight of short-term thinking. Industry and government should be operating according to a 100 year timescale, not a 5 to 20 or 30 year scale, he added.

And this rush to exploit has devastating consequences for caribou.

“The reality is, if you did this in a logical approach, where the highest value resources were exploited first and you left the edges where there isn’t much bitumen, if we put all the people and the infrastructure in the high yield areas, caribou would be happy. Everyone would be happy. But that’s not the way it works.”

The government has further provoked the caribou crisis by allowing critical habitat levels to dwindle down to as low as 5 percent for certain herds. Astonishingly, this figure arose in the federal government’s caribou recovery strategy, despite its clear economic rationale. The amount of intact habitat caribou required for a herd to be considered ‘self-sustaining’ is 60 percent.

With a government operating according to a clear economic mandate, Schneider and his colleagues decided to get creative, which meant finding a way to balance oil production with habitat protection – something the industry and government see as mutually exclusive.

According to Schneider “we could protect 50 to 60 percent of caribou range for less that 1 percent of the resource value of the oil sands, because some areas are far more valuable than others.” The idea is simple: “protect the ‘high percentage’ herds first” in the areas where it will cost the least.

Schneider calculates for high percentage herds by evaluating the cost of protecting herds likely to survive the effects of climate change and habitat fragmentation and then identifies where these ‘favorable’ herds overlap with low-value lease land. Reserving lands with relatively poor production potential could be the cost-effective solution both conservationists and industry could argue for. Schneider and his co-authors call this an “optimization approach.”

But in order for this to happen, the government’s reckless leasing regime would have to change.

“Right now any company can lease land. The government could do this more logically and focus [development] on less than one quarter of the footprint size. We could have 75 percent of the oil sands left untouched and still have the same volume of oil coming from the sands,” Schneider told DeSmogBlog, adding, “it just has to be managed differently.”

Although the government has initiated a poor management plan for both the Tar Sands and the caribou, Schneider sees industry acting as the greatest barrier to the implementation of his caribou recovery plan. “The problem is we have all those leases in place and all those [companies] who have spent millions of dollars buying those leases saying ‘you want to do what? I don’t think so. We paid for them and we are going to exploit them.’”

Schneider anticipates the government will have to work out an adequate compensation plan for these companies, which is a small price to pay for such a profitable restructuring of the status quo.

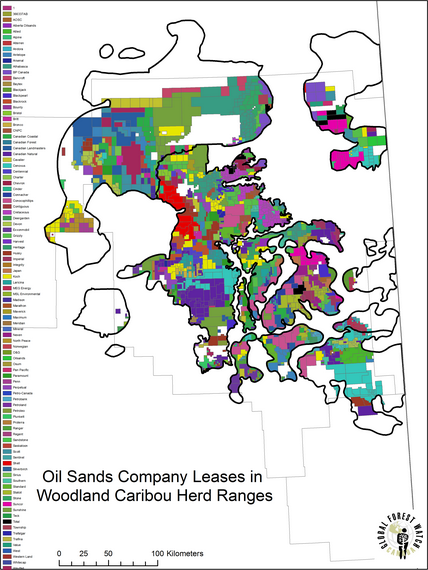

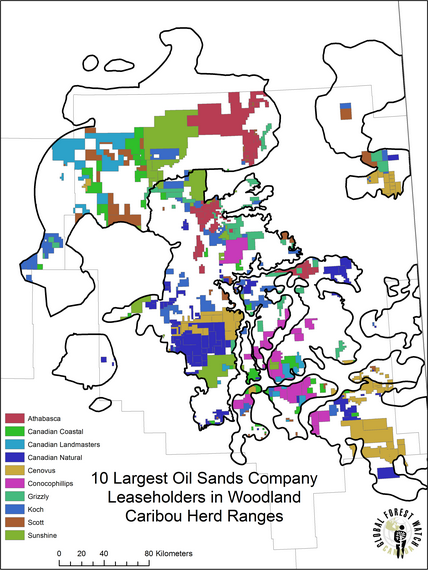

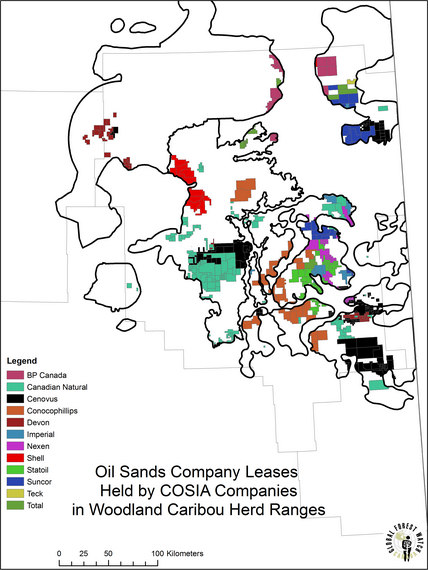

For a detailed list of the companies operating in caribou habitat, take a look at these additional Global Forest Watch Canada digitized maps (pdf links included below). It’s time we started paying more attention to the companies benefiting from the government’s mismanagement of natural resources.

Here is a map dividing the areas by individual company:

This map lists the 10 largest lease holders in the region which include Athabasca Oil Corp., Cenovus, ConocoPhillips, and Koch Exploration Canada:

This map shows leases held in caribou ranges by Canada Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA), a group of Tar Sands major who are committed to “accelerating the pace of improvement in environmental performance in Canada’s oil sands through collaborative action and innovation”:

To learn more about the situation with caribou in the tar sands, watch DeSmogBlog’s investigative short video Cry Wolf: An Unethical Oil Story below:

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts