Think that that dirtiest oil on the planet is only found up in Alberta? You might be surprised then to hear that there are tar sands deposits in Colorado, Utah and Wyoming, much of which are on public lands.

While none of the American tar sands deposits are actively being developed yet, energy companies are frantically working to raise funds, secure approvals, and start extracting.

To help you better understand the state of tar sands development in the U.S., here’s a primer.

Where are the American tar sands?

The Bureau of Land Management estimates that there are between 12-19 billion barrels of tar sands oil, mostly in Eastern Utah, though not all of that would be recoverable.

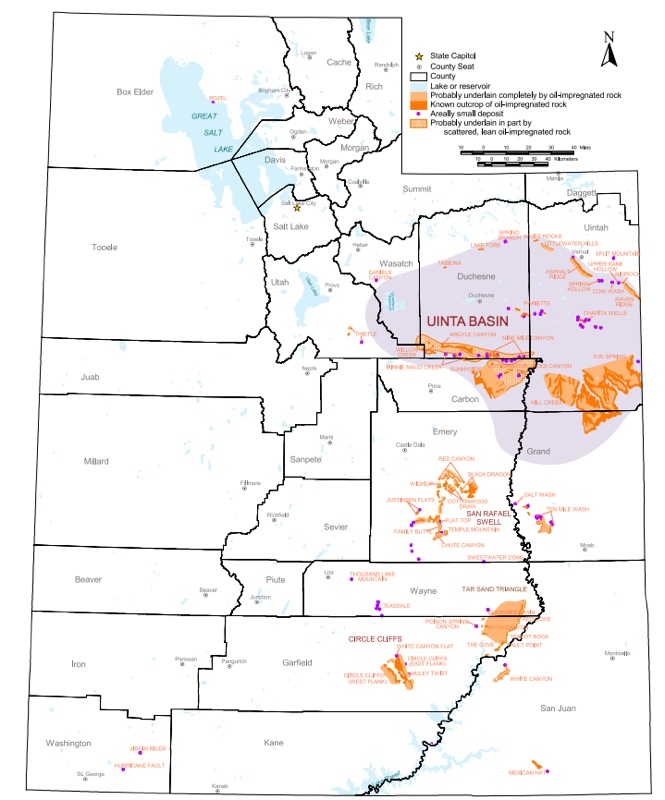

This map from the Utah Geologic Survey shows all of the state’s tar sands.

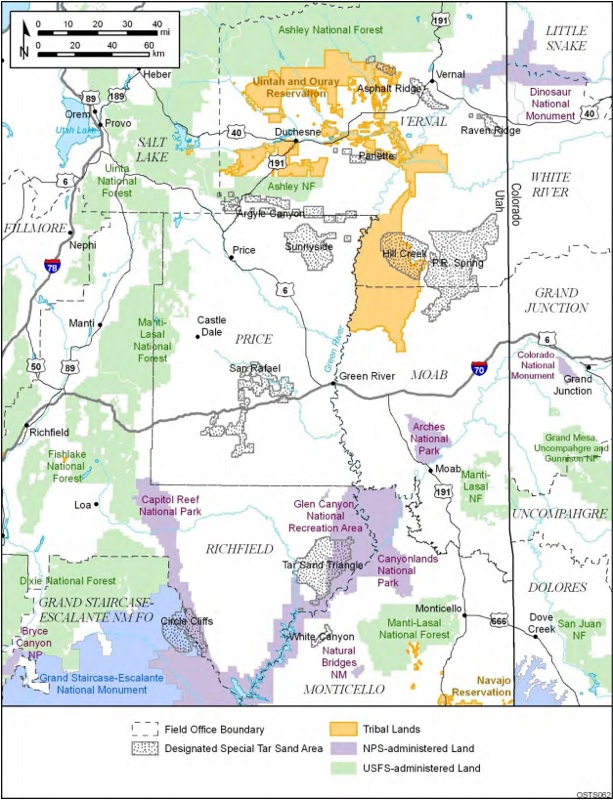

This map from the BLM’s Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PEIS) shows where the U.S. government’s “designated tar sands areas” are located. These are the areas that could, if approved, be developed.

The state of play

In 1981, when James Watt was Ronald Reagan’s Interior Secretary, Congress designated ten Special Tar Sand Areas (STSA) through the passage of the Combined Hydrocarbon Leasing Act of 1981.

Some state-owned lands in Utah have already been approved for speculation, but because of prohibitive costs and limited access, so far only test wells have been drilled.

In 2008, the BLM made roughly 431,000 acres of federal lands potentially available for tar sands leasing and development.

Last spring, the BLM decided to take another look, as new information about the potential impacts on these areas has come to light. Significantly, it also called to reduce leasable tar sands deposits from the 431,000 acres to “just” 91,000 acres.

On February 2, the agency released a Draft PEIS of these so-called “resource management plans,” and that environmental impact statement is now open to public comment until May 4, 2012. Find out more about the EIS and the public comment period at the Oil Shale and Tar Sands Programmatic EIS Information Center website.

Tar sands vs. oil shale

The resource management plans and the EIS don’t only address tar sands development, but also oil shale. It’s important to make the distinction here between the two, as the plight of Albera has made many familiar with tar sands, but oil shale – which has far greater potential for domestic development – is not as well understood.

Here’s how the BLM defines the two:

In this post, we’re focusing on tar sands, but we will explore the oil shale component in a future post.

Who is making a play?

Curiously, the Big Oil developers of tar sands in Alberta have thus far stayed out of Utah. Experts believe that they’re letting smaller companies explore the early stages and determine the economic viability, which is far from certain.

As of today, there are two companies that have taken the lead on U.S. tar sands development.

U.S. Oil Sands Inc.: The highest profile company involved in Utah tar sands development, U.S. Oil Sands is an Alberta-based company that was formerly Earth Energy Resources, Inc (pdf).

U.S. Oil Sands has drilled roughly 180 test wells at the PR Spring Special Tar Sands Area in the Uinta Basin. The PR Spring Tar Sands is located on state-owned land near Arches National Park. U.S. Oil Sands Inc is awaiting approval from Utah state environmental regulators to begin producing oil, which they hope to do by 2013. The state lands the company is developing are surrounded by federal lands that the company also hopes to lease.

U.S. Oil Sands claims to use a more “environmentally-friendly” form of bitumen extraction that uses a citrus-based solvent to mine the tar sands.

MCW Energy: Another Canadian company (though their tag line somewhat dubiously reads, “American oil for America”), MCW is sitting on roughly 1,000 tons of tar sands just 3 miles west of Vernal, Utah. They are awaiting approval to run pilot tests using their own proprietary solvent.

(If you know of others, please let us know in the comments and we’ll update this resource page.)

What’s the problem?

Well, first, there’s the fact that between the extraction, processing, and combustion of tar sands oil, its the most carbon intensive fuel on the planet. But, locally, there are issues as well. One of the biggest, especially in the arid Southwest, is water scarcity.

In 2010, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a report (pdf) that condemned the BLM’s plans to open up so much public land to oil shale and tar sands development, warning of water shortages.

The Colorado Riverkeep group, Living Rivers, is opposed to the projects as well, citing water as their chief concern.

A September 2010 report by Western Resource Advocates, “Fossil Foolishness: Utah’s Pursuit of Tar Sands and Oil Shale” (pdf) rebutted industry claims that 95 percent of the water used would be recycled, explaining that that figure didn’t account for power generation on site, refining and other demands.

But perhaps the best collection of concerns for oil shale and tar sands development come from the development-friendly Utah state government itself.

Living Rivers dug up a memo from Dr. Laura Nelson to former Governor Jon M. Huntsman, Jr. discussing the “impediments” to large-scale oil shale development. At the time of the December 2006 memo, Nelson was serving as Governor Huntsman’s energy advisor. (Nelson went on to become Vice President, Energy and Environmental Development at an oil shale company, Red Leaf Resources.)

It’s worth quoting in full the list of “impediments” discussed in the 2006 memo:

- “Technology for commercial development of both oil shale and tar sands is basically unproven … there are no definite results available that demonstrate commercial viability.”

- “Long-term market prices for crude oil at current levels are not guaranteed. Also, purchases of kerogen are not assured. Price supports and purchase guarantees may be needed to obtain and continue investor participation in tar sands and oil shale technologies.”

- “Both air and water quality issues may be proposed that cause pollution to reach critical levels and need further examination.”

- “Water sources need consolidation so that a reliable and consistent supply is available in the development areas. No specific water supply is set out in preliminary plans for OS/TS development and technologies are still developing. While water supplies are generally available, consolidation needs to be done.”

- “Infrastructure in the way of housing, roads, utilities, and the essential services for workers are lacking at current levels and supplies need to be improved. These are items needing work from both local government and State government.”

- “Available trained labor in the local areas may be limited. … Competition for labor is an inevitability when other industries are working in full force.”

- “Transportation of both raw and refined product as well as workers needs to be assured … transportation is a large enough concern to be in a category of its own.”

- “Refining capacity in the Uintah Basin and in the State as a whole is lacking. As previously discussed, the need for a refinery that will refine more black wax crude oil is already apparent. The entry of kerogen into the mix of supply causes one to consider this an issue with real impact.”

What next?

The public comment period for the BLM’s Draft PEIS closes on May 4. Then the Bureau will take those comments into account and will revise the statement. The Final PEIS is expecting in October, and that will be followed by a 30-day public comment period. Considering that final statement, land-use plans will be finalized by December.

The BLM site has information about how to submit a comment, contact the local BLM office, and other ways to get involved, as well as a useful FAQ section about both oil shale and tar sands development in Utah.

The takeaway

Tar sands development in Utah is not a foregone conclusion. The state lands already available to companies aren’t big enough to justify extraction investment. If lease sales of federal lands are approved, companies will likely start mining.

For more information, visit the sites of these organizations working on the issue:

Living Rivers

Utah Tar Sands Resistance

Western Resource Advocates

For the visual learners and fans of YouTube videos, here is Western Resource Advocates’ “Fossil Foolishness” video:

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts