With efforts to pump tar sands crude south and west coming up against fierce resistance, Canada’s oil industry is making a quiet attempt at an end run to the east.

The industry is growing increasingly desperate to find a coastal port to export tar sands bitumen, especially now that the highly publicized and hotly contested Keystone XL pipeline is stalled, at least temporarily, and the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline project that would move tar sands crude across British Columbia to terminals on Canada’s west coast is running into equally tough opposition.

And by all indications, as laid out in a new report, Going in Reverse: The Tar Sands Threat to Central Canada and New England, by 19 advocacy groups including the Natural Resources Defense Council, Conservation Law Foundation, Greenpeace Canada, the National Wildlife Federation, and 350.org, Enbridge is taking the lead in finding that new outlet.

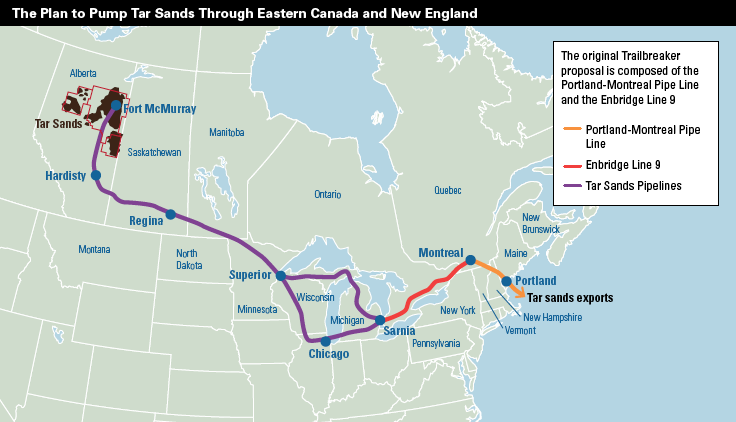

The company is resuscitating an old industry plan to link the pipeline system in the American Midwest to a coastal terminal in Portland, Maine, traveling through Ontario and Quebec, and then across northern New England. When first proposed in 2008, this project was called Trailbreaker, but Enbridge appears to be avoiding any mention of the former proposal, which spurred quick and firm resistance.

Despite the fact that Enbridge isn’t as vocal about this eastern route as they are about the Northern Gateway proposal, there are a couple of reasons to take it as seriously.

First, the revived Trailbreaker plan doesn’t require new pipelines to be built, but would rather reverse the flow of two existing pipeline systems, one in Ontario and Quebec, and another that links Montreal to coastal Maine. Here’s how the “Going in Reverse” report describes the two systems:

Enbridge Line 9 travels a path more than 500 miles fromrefineries in Sarnia, Ontario, to a refinery in Montreal. For long stretches of Line 9’s route, the pipeline roughly follows Highway 401 as it skirts to the north and northwest of Lake Ontario and the Saint Lawrence River.5 Currently, Line 9 carries conventional light oil. The pipeline is 37 years old.

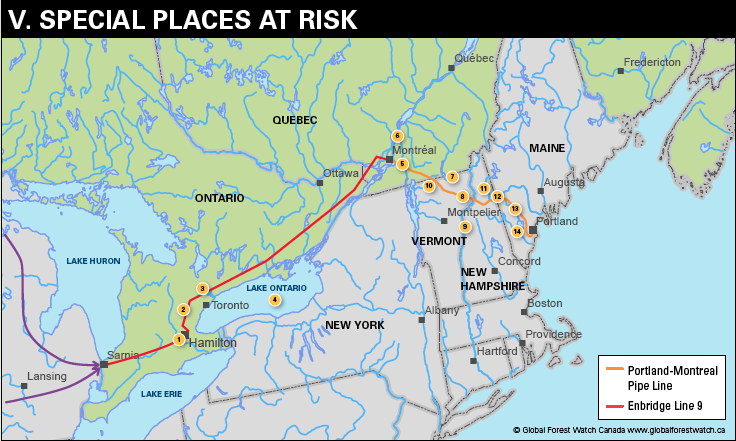

The Portland-Montreal Pipe Line consists of two parallel, 236-mile pipelines that link Montreal refineries at the eastern end of Line 9 with a crude oil terminal near the tanker port at South Portland, Maine.7 The pipeline travels across northern Vermont and New Hampshire, as well as western Maine.7 The pipeline that would be reversed is 62 years old and currently carries light to medium crude sourced from overseas.

Second, Enbridge and industry friends are seeking approval on a piecemeal basis, which could prove easier to accomplish than if they needed to secure approval of the entire system.

Where do things stand?

As of last August, Enbridge applied for a permit with the Canadian National Energy Board that seeks to reverse the flow of about one quarter of Line 9’s length – from Sarnia, Ontario to the Westover Oil Terminal outside of Hamilton, Ontario. Enbridge has claimed that this is a standalone project, which seems odd considering the fact that it is literally titled “Line 9 Reversal Phase 1.” (pdf).

Last month, Enbridge confirmed its plans to reverse the flow of Line 9 all the way to Montreal, allegedly “to serve refineries in Quebec.”

Desperate as they are to access export terminals, and considering the fact that just four years ago they laid out these exact same plans as part of the Trailbreaker project that would connect to Portland, Maine, it’s hard to believe that their eastward expansion hopes end in Montreal.

Onward to Maine?

Enbridge only controls the pipelines up to Montreal. From Montreal to Portland, the lines are owned by two related companies, which have publicly expressed interest in reversing the flow of their lines to sync up with Enbridge’s Line 9 reversal plans.

The “Going in Reverse” report explains:

The Portland-Montreal Pipe Line is managed by two linked companies: the Montreal Pipe Line Limited, which owns and operates the Portland-Montreal Pipe Line with its wholly owned U.S. subsidiary, the Portland Pipeline Corporation.

The Portland-Montreal Pipe Line company, as well as Enbridge Inc., have been open about their intent to move tar sands oil east through central Canada and New England. In 2011, Portland Pipe Line Corp. expressed publicly, “We’re still very much interested in reversing the flow of one of our two pipe lines to move western Canadian crude to the eastern seaboard,” treasurer Dave Cyr was reported saying. “We’re having discussions with Enbridge on their Line 9 and what it means to us.”

Montreal Pipe Line Limited has backed up these words with some actions. The company has applied for a permit to build a pumping station along its right-of-way in Quebec, which would allow for the oil flow to be reversed on the Portland-Montreal link. In February, however, a Quebec judge denied the permit.

And get this: Montreal Pipe Line Limited is owned in large part by Imperial Oil Limited and Suncor Energy

What’s at stake? Besides the expansion of tar sands crude shipments, and all the tremendous volumes of carbon pollution inherent therein, the potential reversal of Line 9 and the Portland-Montreal line poses an incredible threat to the land and local communities through which these lines flow. As we’ve covered before, there are many problems with shipping tar sands crude – which is particularly abrasive, acidic, and flows at uniquely hot temperatures – through pipelines, particularly older ones that were built to funnel lighter, gentler crude. The threat of a spill from a tar sands pipeline is far greater than from one carrying conventional crude. And when there is a spill, as evidenced in Enbridge’s own Kalamazoo River disaster, it’s far harder to clean up, and the impacts on the local community can be devastating. The “Going in Reverse” report spotlights a handful of environmentally-sensitive and economically-critical areas through which Line 9 and the Portland-Montreal line pass. It’s well worth downloading the full report to see photos and descriptions of these spots that could soon be even more vulnerable if the tar sands crude starts flowing. What next? The 19 organizations behind the “Going in Reverse” report are calling for Canada’s National Energy Board to consider Enbridge’s Line 9 reversal permit application to be a part of a broader plan to ship tar sands crude east to coastal Maine. A broader assessment would consider the impacts of a revised Trailbreaker project on climate change, expansion of tar sands production, the increased risks of pipeline spills, and the increases in pollution at refineries along the route. Meanwhile, New Englanders should be well aware of the industry’s intentions: to ship tar sands crude all the way from Alberta, through Ontario and Quebec, and then down through Northern New England to a port in Portland, Maine. New Englanders need to know that they’re looking down the barrel of a tar sands pipeline. Maps: Going in Reverse: The Tar Sands Threat to Central Canada and New England

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts