In the past three months, I’ve spoken on panels at two scientific mega-conferences—the American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting in San Francisco, which draws tens of thousands of scientists, and the annual American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) meeting, which this year was held in Vancouver (and pulls in about eight thousand).

As a science communication trainer and advocate, I’ve noticed much at these events that makes me very hopeful. More so than ever before, these conferences are thronged with panels on how to improve science communication, particularly with respect to pressing concerns like climate change. Indeed, a powerful theme at the AAAS meeting, articulated by organization president Nina Federoff, was that science is under attack—an attack that must be countered, including through direct-to-public communication efforts by scientists themselves (of which the excellent communicator Michael Mann provides a great recent example).

Federoff is absolutely right in her message. Science communication is, indeed, vital—and scientific organizations like AAAS and the AGU are driving a very welcome change in scientific culture with their efforts.

But here’s the thing: While these organizations have the best of intentions, there may be inadvertent aspects of what they do that actually undermine their stated goals. In particular, in this piece I’m going to argue we can make science communication better not only by having lots of panels on the matter, but by changing some very simple and basic things about how scientists present their knowledge at conferences like AGU and AAAS.

At the outset, let me note that I am not criticizing the American Geophysical Union or the American Association for the Advancement of Science. They have the task of managing vast events featuring thousands of scientists’ presentations, and may be unaware of the problems I’m about to outline. However, I do want to make them cognizant of the implications of some of the choices they make for science communication, both to the public and also in the classroom and teaching context—rather large implications that they may not have considered.

Also, since this post is about uses and misuses of PowerPoint, let me just say at the outset that I used to suck at using this program too, and made many if not all of the mistakes that I’m about to describe. I learned better thanks to some great teachers and colleagues, like Dan Agan, mentioned below. I realize that not everyone has been as fortunate as me in this respect—but in writing this piece, I’m hoping to give a little back, and share some of the knowledge that made me a much better public presenter than I used to be.

The Conference is the Thing. My focus on how scientists present at mega-conferences is not accidental. These conferences are, for many scientists, their number one opportunity to engage in the act of communication. Their talks, to be sure, are aimed towards their peers rather than public audiences. But nevertheless, the techniques and practices inculcated here surely have an oversized impact on scientists’ broader communication activities—including their classroom activities (where bad habits are also common).

At scientific conferences, the vast majority of presenters use Microsoft’s ubiquitous PowerPoint program—and here’s where the troubles sometimes start. Used well, PowerPoint can lead to great presentations (though I know others swear by programs like Prezi and Keynote). But used poorly…well. Wince.

At scientific conferences, we certainly do see many good PowerPoint talks. But we also see many cases of PowerPoint being used poorly. I think the causes of this are both cultural but also structural—e.g., at least partly tied to the mechanics of how the conferences themselves work.

But for precisely this reason, the conferences could do something about it.

That’s what I’m going to suggest—but first, let’s examine what it means to use PowerPoint badly. I’ll then show how scientific conferences seem to subtly (if unintentionally) encourage this—and finally, how they can fix matters.

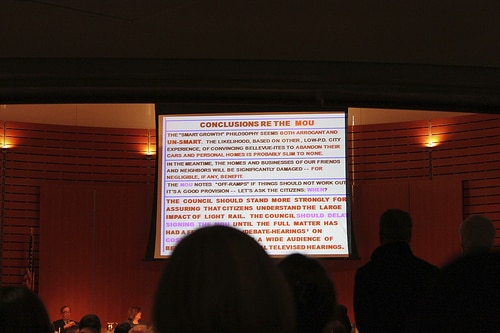

Caught in a Bad PowerPoint. A cardinal sin of PowerPoint is putting lots of tiny words up on the screen, and then, basically, reading your notes to the audience. It certainly isn’t only scientists who do this—you see it everywhere. But scientists are often guilty parties in this respect.

What’s wrong with words on the screen? Well, I have to thank my fellow communication trainer Dan Agan for explaining this to me, powerfully and lucidly.

When we teach scientists to communicate at the National Science Foundation “Science: Becoming the Messenger” workshop, Agan covers PowerPoint, and he stresses the importance of using your slides to visually enhance the talk, rather than just to put your own crib notes up for everybody to see. Dan even remarks that doing it the latter way is sort of like filming a movie by slowly scanning the camera over the script, so the viewers can read it.

Obviously nobody would do that—and nobody would want to watch such a movie. But why, then, do so many people put their notes on the screen when they use PowerPoint?

It can’t be because audiences enjoy being read to. They don’t. It is both boring and also distracting to try to read words on a screen while also listening to someone talk. It’s a walk-and-chew-gum kinda thing. It is much easier for audiences to listen to you talk and simultaneously take in images that enhance what you’re saying, than for them to listen to you talk and also read the points you are making.

So if that’s not the explanation for overly wordy slides, then what is?

Well, one explanation may simply be the “need for notes”—you haven’t memorized your talk, and so either you have to print out notes physically, or you have to have them there to look at.

Yet another possibility for slide wordiness is that scientists like to exchange their presentations with colleagues. And it feels odd to share a PowerPoint that is all images and no words—how is anyone who wasn’t there supposed to know what you said?

These are certainly excuses. They just aren’t very good ones.

You see, you can have your notes in front of you, and you can have a sharable PowerPoint presentation, without ever having to put long sentences up on the screen for your audience to try to read. All you have to do is design and present your presentation in PowerPoint’s “presenter view,” which is really the best and, frankly, the only way to use this program.

In presenter view, your notes are there for you to see, but you don’t have to show your speakerly underwear to the audience too. Instead, what they see can be striking images and (hopefully) well designed and clear graphs and figures that enhance the point that your making.

You can also share presentations created for PowerPoint presenter mode, and include the notes so your colleagues can see them. Just convert the document to a PDF, and then your hidden notes can be included along with the slides themselves.

So why don’t more scientists use presenter view? Well, I’m sure many just don’t know it exists. But it seems to me that the scientific conferences are also partly involved here.

Look in the Mirror. Scientific conferences have to manage very large numbers of scientists who have arrived to give presentations. It is a big logistical headache, and accordingly, there is a standardized way of uploading your PowerPoint presentation at a “speaker ready room.” And then, when you are actually presenting on your panel, there is usually one computer where all of the presentations reside, and then they’re called up one by one.

This is where the trouble begins, and I’ll have to get a tad technical for a moment to explain why. Bear with me, because the details really matter in this case.

At the American Geophysical Union meeting, I was told that my presentation could not be delivered using PowerPoint’s presenter mode. The reason I could not do so was because the projector in the room was configured to “mirror” the computer’s desktop.

In other words, whatever I saw on my screen would also be what the audience saw. PowerPoint’s presenter view, in contrast, requires “extending” the desktop so that you see one thing, and the audience sees another. (Microsoft has the deets on mirroring versus extending here.)

At the AAAS meeting, things weren’t quite so forced. I was able to figure out a way to use my own laptop, rather than the group computer, and so I managed to “extend” the desktop that way. But this was more because I found a way around the standard setup than because the standard setup is a good one. And I imagine that most scientists at AAAS once again found themselves in “mirror” mode, and therefore were not using PowerPoint’s presenter view.

In other words, it look likes scientific conferences may be subtly pushing scientists away from a better use of PowerPoint. Certainly that was the case for me, and I doubt I am unique in this respect.

It’s not just the way “speaker ready rooms” work, though, or desktop-to-projector mirroring, that we need to focus on. It’s the unspoken assumption that these kinds of little details aren’t really very important. To the contrary, I believe they can make all the difference between a good presentation and a bad one. Knowing this, a tuned-in science communicator will pay a great deal of attention to them. And so will a scientific society hoping to foster such communicators.

Extend Your Presentation’s Appeal. So what should the conferences do? Simple. Think hard about the implications of seemingly “little” conference details for how scientists end up practicing the art of communication.

So, for instance, one simple switch would be that instead of setting up all the computers to mirror, set them all up to extend, and force all presenters to learn presenter mode. Make a big change in a simple norm, do so in the name of better science communication—and watch as literally thousands of scientists dip into a bag of new tricks.

Now, to be sure, one objection to this line of argument may be that at scientific conferences, scientists are communicating to their peers, not to the public. And scientists are used to talks that have lots of words on the screen, so no harm done.

I disagree. First, I don’t think it unreasonable to assume that the practices used in presenting at scientific conferences will also spill over into public presentations, and also into teaching. And moreover, what I’m trying to inculcate here is audience sensitivity—whether your audience is scientific or otherwise. Paying attention to the audience, making sure that the audience is not bored or turned off by you…these are all very basic habits that good communicators must develop.

Sometimes, little details go a long way. And if we want to create an environment that is friendly to effective science communication—to walk the walk—they must not escape our attention.

[Image credit: Oran Viriyincy, Flickr, Creative Commons]

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts