We’ve talked a lot here on DeSmogBlog about oil (and tar sands crude) pipelines. You know, like the Keystone XL, which TransCanada is currently ramming through Texas, using whatever means necessary (including violence), and Enbridge’s Northern Gateway, which was just declared “dead” by one of Canada’s top newspapers.

And we’ve talked quite a bit about coal trains. All for very good reason. But we haven’t ever delved into the growing trend of shipping oil by train. Trains are a crucial – and growing – part of oil industry infrastructure, so it’s worthwhile to take a step back and get some perspective on this remarkable system. Understanding oil trains will help you understand, for instance, why oil markets are paying little attention to the pipeline debates.

Let’s start with the raw numbers.

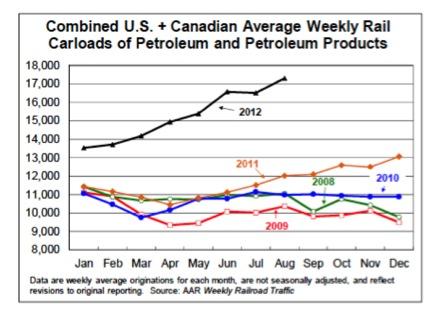

Every week, over 17,000 carloads of oil are shipped in the U.S. and Canada. With roughly 600 to 700 barrels of oil in each carload, that’s between 1.4 and 1.6 million barrels of oil on the U.S. and Canadian rails every day. And these numbers are growing fast. This chart says it all.

(I should clarify and say that these numbers represent the total amount of oil and natural gas liquids (NGLs), but as much digging as I did in the Energy Information Agency stats and Association of American Railroad reports, I couldn’t find any good data to break it down any further.)

What’s responsible for the recent surge in oil and NGL on the rails? Mostly the rapid development of the Bakken shale plays under the Obama administration. The expansion of Alberta tar sands extraction is also definitely playing a role.

Pipelines are far cheaper and more efficient for shipping oil, so companies would rather send crude through pipes than load it onto trains. But in areas where pipeline access is limited – like the North Dakota Bakken shale – trains become the next best alternative.

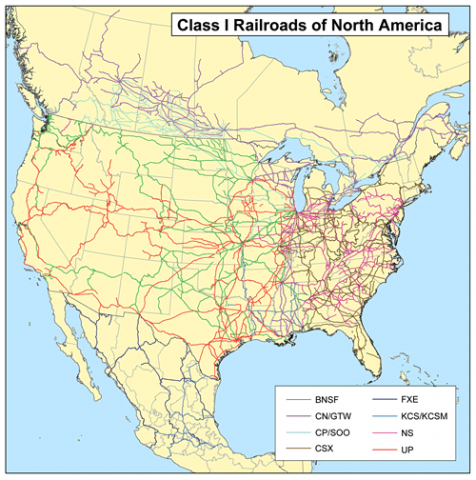

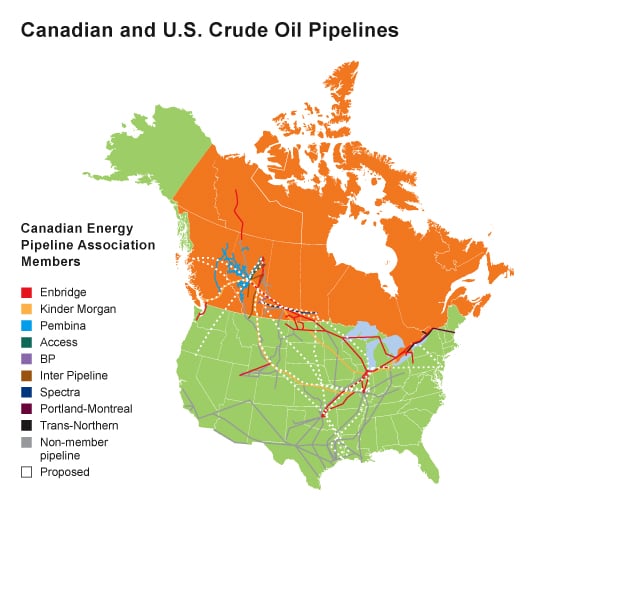

Compare these maps of oil pipelines (from our earlier Pipelines 101 post) and Class I railroad lines:

Obviously, the extension rail system can get tanker cars full of oil into and away from a lot more regions. Not that every region really matters. What matters most is connecting the wellheads (or sources) to the refineries.

So looking at that pipeline map, you might wonder why the rail is necessary for the Bakken boom. Isn’t it well served by the Enbridge and Kinder Morgan lines? The answer is: yes and no. Yes, it’s served by those pipelines. But not well enough for the industry.

To put it bluntly: those pipelines out of the Bakken are maxed out. They’ve been operating at capacity for the better part of five years. So much so, that the production of the entire region was limited by pipeline capacity until mid-2010 when rail shipping kicked in. Since then, rail shipments have been steadily climbing, as companies have scrambled to build new higher capacity terminals in order to move more crude.

Whatever your personal feelings about oil, there is also one big technical problem with the flurry of oil train traffic on North Dakota’s rails: as the industry trade newsletter from RBN Energy puts it, “the rail lines in North Dakota were not built for this kind of traffic.”

In rail parlance, there are main lines and branch lines. The main lines are the superhighways designed for heavy traffic. The branch lines are the back roads. Most of the branch lines in North Dakota were built to support agriculture – to carry fertilizer at the beginning of the growing season and the grain harvest at the end. It is these branch lines that are now being used to transport crude cars. The traffic is heavy and continuous, resulting in much more wear and tear on the lines.

Two such major projects were announced this year. The first, in St. James, Louisiana, will serve the entire Louisiana Gulf Coast refinery district. Another, perhaps more surprising, is in Albany, NY, where Global Partners, LLC more than tripled their capacity to offload Bakken crude from trains, with the intention of putting it on barges and shipping it down the Hudson River to East Coast refineries.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts