After nearly a decade of engineering work on the project, the Panama Canal’s expansion opened for business on June 26.

At the center of that business, a DeSmog investigation has demonstrated, is a fast-track export lane for gas obtained via hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in the United States. The expanded Canal in both depth and width equates to a shortened voyage to Asia and also means the vast majority of liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers — 9-percent before versus 88-percent now — can now fit through it.

Emails and documents obtained under open records law show that LNG exports have, for the past several years, served as a centerpiece for promotion of the Canal’s expansion by the U.S. Gulf of Mexico-based Port of Lake Charles.

And the oil and gas industry, while awaiting the Canal expansion project’s completion, lobbied for and achieved passage of a federal bill that expanded the water depth of a key Gulf-based port set to feed the fracked gas export boom.

Control of the Panama Canal by U.S. big business and Wall Street has, for over a century, served as a focal point of U.S. foreign policy in the Americas.

While no longer in de facto control of the isthmus as it was during the days of the Panama Canal Zone, Jill Biden’s presence as part of an official Presidential Delegation at the expanded Canal’s opening ceremony symbolized the importance of the waterway and de jure role of the U.S. government in pushing for its expansion over the past several years. So too did the attendance of the U.S. military’s Southern Command (SOUTHCOM).

And in turn, the reported participation of LNG exports giant Cheniere Energy at the kick-off serves as a portrayal of the importance of the Canal’s expansion to the oil and gas industry. The Panama Canal Authority estimates that 20 million tons of LNG may pass through on an annual basis.

“The volume projected by the Panama Canal Authority represents about 8 percent of global LNG trade and is equivalent to nearly 300 ships a year,” Bloomberg explained.

In a press release announcing the Canal expansion’s opening, LNG shipments receive a prominent mention.

“We are thrilled that we currently have 170 reservations for Neopanamax ships, commitments of two new liner services to the Expanded Canal, and a reservation for the first LNG vessel, which will transit in late July,” Jorge Quijano, CEO of the Panama Canal Authority, stated in the release. “Our customers care that their supply chain is reliable and that they have a diversity of shipping options. And the Canal has always been reliable; today, we offer the world new shipping options and trade routes.”

It has taken a rigorous lobbying and influence peddling effort by the oil and gas industry to make the looming first LNG shipment through the Canal a reality.

Lake Charles LNG MOUs

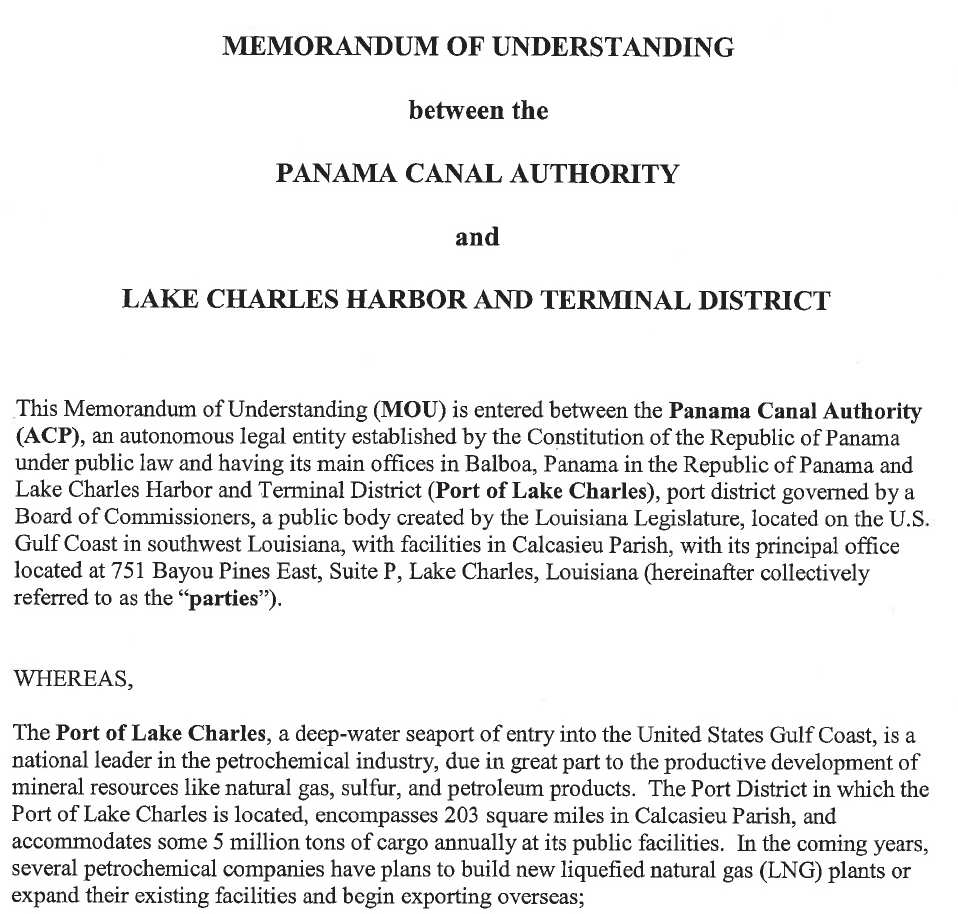

In January 2015, Port of Lake Charles officials signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Panama Canal Authority officials.

The MOU explicitly mentions the role the Canal could play in opening up the global spigot for LNG exports and a fast-lane to Asia. A sign of the importance of the Canal’s expansion to Asia, the Japan Bank for International Corporation signed a loan agreement with the Panama Canal Authority in December 2008 for $800 million. Japan, in the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, has shifted its energy portfolio in the direction of increased reliance on natural gas and LNG imports.

Image Credit: Port of Lake Charles

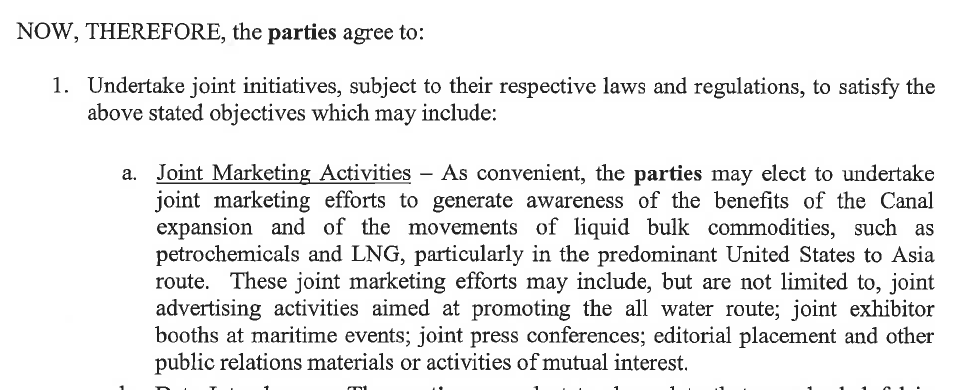

Officials involved with the effort signed the MOU at the Louisiana-based Port of Lake Charles in an event that featured invitations sent out to executives of the seven Lake Charles-based LNG companies. In the aftermath of signing the MOU, Quijano held a meeting with the LNG company representatives present at the ceremony.

Image Credit: Port of Lake Charles

The Port of Lake Charles houses the approved Sempra LNG facility and the proposed Trunkline LNG and Magnolia LNG facilities.

Matt Young — then the public relations director for the O’Carroll Group public relations firm and current public information officer for the City of Lake Charles — wrote the talking points for the MOU ceremony for Port of Lake Charles officials. At the time and as of April, O’Carroll oversaw the public relations and marketing work for the Magnolia LNG.

Industry Lobbies to Re-engineer Sabine

Beyond the MOU with Lake Charles, the oil and gas industry also used its lobbying prowess to win federal tax dollars that would go toward deepening and re-engineering ports and key coastal waterways in service to industrial interests such as LNG exports. They did so via the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (H.R. 3080).

Those lobbying for H.R. 3080 included the likes of LNG trader Koch Industries, LNG industry giant BG Group (now owned by Shell), Sempra Energy (owner of the Lake Charles-based Sempra LNG facility), Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA), American Petroleum Institute (API), BP America and ExxonMobil.

BP, Bloomberg has reported, is set to send the first LNG tanker through the Panama Canal in July.

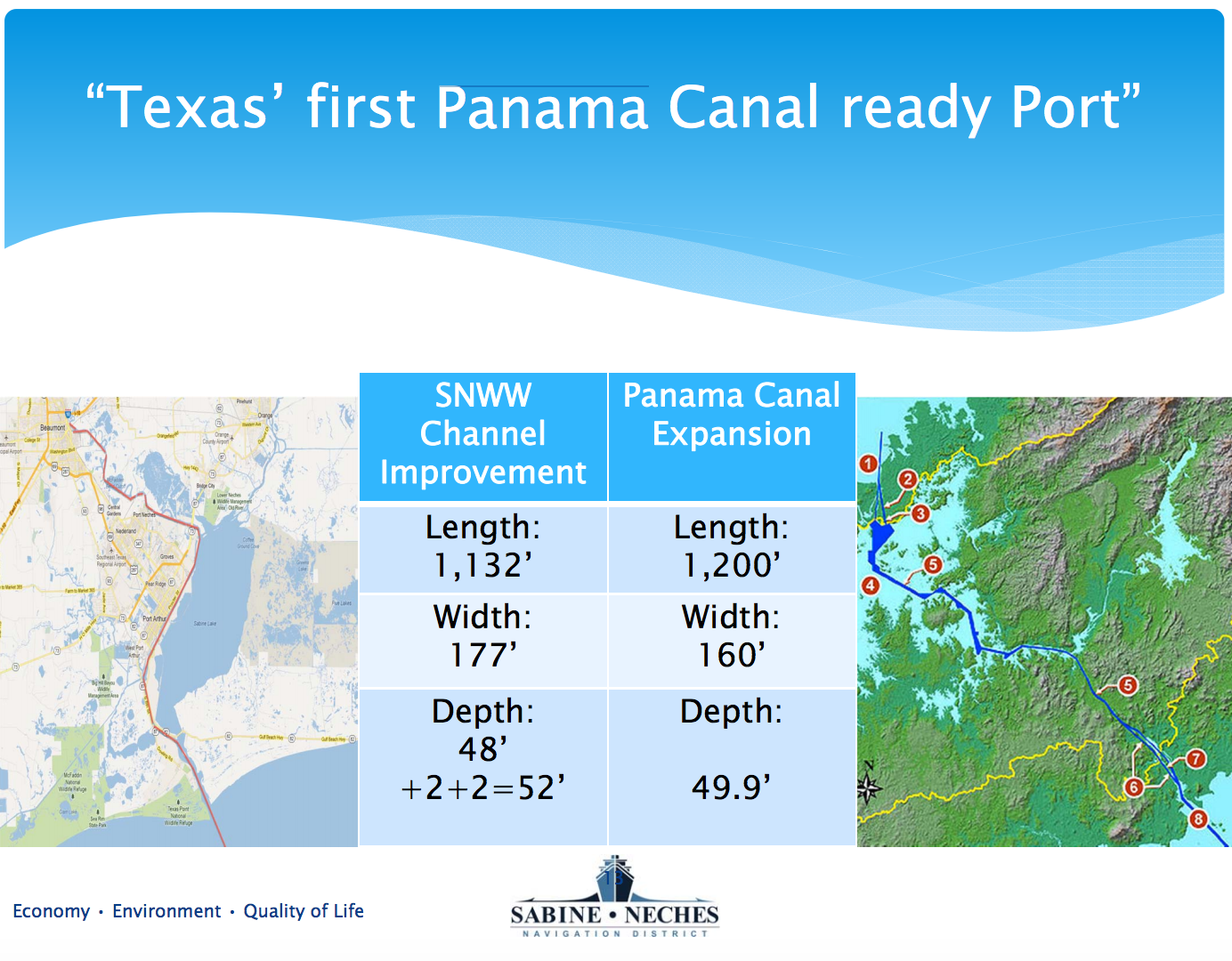

The bill “includes the deepening of the Sabine-Neches Waterway to 48 feet from its current 40 feet. The entire bill is for 34 projects across the country with a price tag of $12 billion,” explained the Beaumont Enterprise. “The Sabine-Neches project, listed first in the bill, would be funded at $748 million and is 75 percent of the project cost.”

Sabine-Neches connects to Cheniere’s Sabine Pass LNG facility, ExxonMobil’s proposed Golden Pass LNG facility and Sempra’s LNG facility. According to the Sabine-Neches Navigation District website, the Waterway is “projected to become the largest LNG exporter in the United States.”

In a PowerPoint presentation from August 2012, the Sabine-Neches Navigation District boasted that it could soon become “Texas’ first Panama Canal ready Port.”

Image Credit: Sabine-Neches Navigation District

A May 2014 article published by Bloomberg overtly links the bill’s passage with the expansion of both the Panama Canal and the Sabine-Neches Waterway.

“House and Senate negotiators reached agreement on a bill that would authorise deepening several US ports ahead of the expansion of the Panama Canal and the bigger ships that will use it,” reads the article. “The Port Arthur area is home to the southern end of the Keystone XL pipeline. Deepening the port will reduce shipping costs for oil and natural gas processed there by Exxon Mobil, Total and Cheniere Energy.”

BG Group, which lobbied for the port expansion legislation, said in its quarter four 2010 investor call that the opening of the Panama Canal means more trade and business opportunities for the company.

“Stolen Property”

In a July 2015 article published in Platts, a Panama Canal Authority official stated that he expects relatively little LNG export-centric traffic in the Canal through about 2020, as Gulf of Mexico-based terminals await approval by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

“The first two years of operations [after the 2016 expansion] we expect few transits per year because only one export terminal from the Gulf of Mexico will be operational,” the Canal official told Platts. “As more terminals come online, traffic of LNG carriers should pick up after 2016…until reaching around three transits per day after 2020.”

Oscar Bazán, the Panama Canal’s executive vice president for planning and development, recently told The Wall Street Journal that by 2020, LNG tankers could be the main cargo sailing through the Canal.

Like the story of the Panama Canal’s expansion and the myriad LNG tankers which soon may pass through it, the Canal’s origins tie back to lobbying and the realization of corporate and Wall Street interests. This was noted in a 1903 editorial penned by The New York Times.

“In order rightly to understand what we are doing we must acknowledge to ourselves that this territory through which we are to build the canal is stolen property, that our partners in the theft are a group of canal promoters and speculators and lobbyists,” opined The Times, proceeding to write that whether the U.S. goes through with the deal or not “the world will get a true measure of the American conscience.”

Given the life-cycle greenhouse gas impacts of fracking and shipping LNG across the planet for climate change in today’s context, it could reasonably be argued that what the U.S. and industry are doing this time around is unconscionable.

Photo Credit: Panama Canal Authority

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts