A federal judge’s recent order stopping construction of the Bayou Bridge pipeline — though only in Louisiana’s Atchafalaya Basin — has successfully prevented further sections of the National Heritage Area from being destroyed, for now.

On February 27, the same day U.S. District Judge Shelly Dick explained her previous week’s ruling to halt work on the pipeline, Dean Wilson, executive director of the Atchafalaya Basinkeeper, surveyed the oil pipeline’s route in the basin. He was relieved to find cypress trees recently identified as “legacy trees” — those which were alive before 1803 — still standing.

I spoke to Wilson after he toured the pipeline route. He told me he was relieved to discover much of the route through the basin’s east side still intact. The damage done on the west side was heartbreaking, but at least the pipeline has yet to be put in the ground, he said.

Watch: Aerial view of Bayou Bridge pipeline construction through Atchafalaya Basin

Drone video shot by Phin Percy, an independent camera operator, shows the pipeline route on the west side of the basin, where a swath of trees up to 75 feet deep has already been pulverized.

In a 60-page decision, Judge Dick clarified her reasoning for granting the request to stop pipeline work in the basin, despite the protest of Bayou Bridge Pipeline LLC’s main owner Energy Transfer Partners. “The Court finds the temporary delay in reaping economic benefits does not outweigh the permanent harm to the environment that has been established as a result of the pipeline construction,” Dick wrote.

The judge ruled in favor of the environmental groups, which include Atchafalaya Basinkeeper and are represented by EarthJustice, in their lawsuit seeking to revoke a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers permit for the Bayou Bridge pipeline. Earthjustice argued that running the pipeline through the Atchafalaya Basin risks permanent and irreparable damage to the basin’s water flow and will destroy old growth cypress trees that would not regrow along the pipeline route.

The February 27 ruling makes clear that the injunction only halts work on the pipeline in the Atchafalaya Basin. Construction along the rest of the 162.5-mile route, which began in January, can continue. The Bayou Bridge pipeline’s proposed route from Lake Charles to St. James, Louisiana, is set to cut through the Atchafalaya Basin, a National Heritage Area and the country’s largest river swamp. The next question for the courts is whether Energy Transfer Partners will be forced to reroute the pipeline to avoid the environmentally sensitive basin.

One of the old growth cypress trees saved by the injunction on the Atchafalaya Basin’s east side.

Wilson told me that detouring the pipeline around the basin could preserve the environmentally sensitive area. He estimated such a detour might be roughly 65 miles.

Alexis Daniel, a spokesperson for Energy Transfer Partners, which is also behind the Dakota Access pipeline, wouldn’t comment on whether the company has considered re-routing the pipeline following the judge’s ruling, citing pending litigation.

“Bayou Bridge Pipeline respectfully disagrees with the District Court’s ruling that the Army Corps of Engineers did not properly consider the limited impacts of construction in the Atchafalaya Basin during the extensive [National Environmental Policy Act] process the Corps conducted,” according to a statement Daniel provided. The company plans “to seek immediate relief from this decision in the appropriate courts.”

According to Energy Transfer Partners, “The Corps issued two comprehensive environmental assessments, both of which had a ‘Finding of No Significant Impact to the Basin.’” And its lawyers pointed out that the permit compels the company to restore the basin’s “pre-existing wetland contours and conditions” after completing construction.

At the same time, Judge Dick wrote that the Corps failed to demonstrate it took a “hard look” at “cumulative” environmental impacts, including those in the past and future. “The Corps’ and (company’s) myopic view that they are only required to consider the impacts of this singular project is not consistent with the regulations or applicable jurisprudence,” she wrote.

The lawsuit Earthjustice filed against the Corps in federal court on January 11 alleges that the Corps is not enforcing existing permits for oil and gas pipeline companies already operating in the basin. Considering this week’s ruling, Earthjustice’s lawsuit may need to be heard before the injunction is lifted.

That lawsuit also contends that the Corps’ assessment wasn’t the only one needed before the agency could issue a permit, claiming that an Environmental Impact Study (EIS) was needed first. An EIS is required by the National Environmental Policy Act for actions that significantly affect the quality of the environment and is used as a tool for federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of their proposed actions prior to making decisions.

Who Is Monitoring Construction of the Bayou Bridge Pipeline?

Rick Boyett, Chief Public Affairs Spokesperson for the Corps, listed the agencies responsible for monitoring construction of the pipeline.

“Multiple agencies, such as the Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration (PHMSA), Office of Pipeline Safety (OPS), LaDEQ [Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality], and DNR [The Department of Natural Resources] will also be overseeing the construction of the pipeline. Additionally, tribal monitors will be onsite during construction,” he wrote in an email.

I followed up with the state and federal agencies Boyett listed, asking what their roles might be in pipeline construction projects.

Gregory Langley, spokesperson for LDEQ, said, “LDEQ does not have a specific role in oversight of the construction of pipelines.”

As for DNR, the agency is only involved with the “approximately 17-mile section of the project that is within the Coastal Zone,” according to Patrick Courreges, DNR’s public affairs spokesperson.

Boyett won’t say exactly who the “tribal monitors” he mentions are. I asked Earthjustice if the organization knew who the tribal monitors might be. My sources told me they checked with everyone they could think of, but no one knew who might play a role in monitoring the construction.

PHSMA has yet to clarify its role in overseeing the installation of the Bayou Bridge pipeline. Darius Kirkwood, a representative with PHMSA, emailed me on January 29, saying that they were working on getting me an answer, but the agency has been non-responsive since then.

Despite the apparent ambiguity around which agencies should be overseeing this project, the pipeline’s construction is not going unobserved. The environmental groups involved in the lawsuit against the Corps, along with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade and participants in the L’eau Est La Vie (Water is Life) protest camp, have taken to monitoring the pipeline’s installation on their own.

“We have reports from our members that construction on Bayou Bridge Pipeline is filling in Bay Barron and Crocodile Bayou with sediment. This is illegal according to construction permits,” Scott Eustis of Gulf Restoration Network, which is involved in the lawsuit, told me via email. “The flow of water needs to be restored to the Atchafalaya Basin to bring this sediment to the coast.”

Dean Wilson reported to the Corps that he found a pile of branches left by construction workers that blocks a bayou. And Cherrie Foytlin, a founder of the L’eau Est La Vie camp, contacted the Corps after she found oil sheen in wetlands next to a site she monitored near the basin’s west side.

‘Water Protectors’ Push Back Against Pipeline Construction

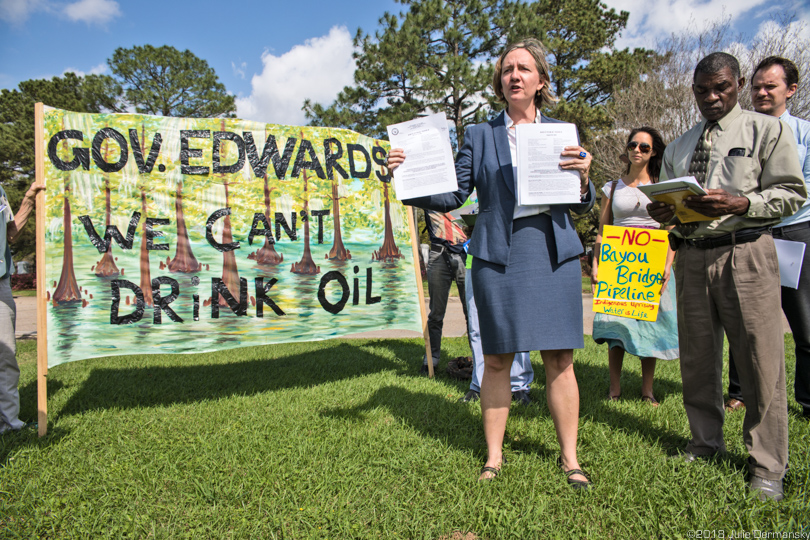

Direct action taken to shut down construction of the Bayou Bridge pipeline in Belle Rose, Louisiana, outside of the Atchafalaya Basin.

Three people removed by police after refusing to get off a piece of pipeline during a protest against the Bayou Bridge pipeline.

Meanwhile, direct actions against the oil pipeline project have begun. On February 26, around two dozen protesters calling themselves “water protectors” shut down a construction site outside of the Atchafalaya Basin for two hours. Three of them were arrested after refusing police orders to disperse and were charged with resisting arrest and trespassing. They were released, pending hearings set in May, according to Renate Heurich with the climate justice group 350 New Orleans, who also took part in the direct action.

Main image: Rae-Lynn Cazelot of the United Houma Nation, holding a sign during a protest at a Bayou Bridge pipeline construction site. Credit: All photos © Julie Dermansky

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts