Most people probably aren’t familiar with the acronym ZIRP. It stands for zero interest rate policy and is the policy that unintentionally created the American fracking bubble — just one of its many consequences.

And while most people may not know much (if anything) about ZIRP or the Federal Reserve (Fed), it is likely that they are aware of the impact this policy has on their own lives.

Do you have money in your checking account? Are you lucky enough to have savings? Have you noticed how you don’t make any interest on that money and haven’t for almost 10 years?

You can thank the Fed and ZIRP for that. One of the results of the Fed’s zero interest rate policy is that the average American saver ends up with close to zero interest on their money in the bank. This is one of the reasons that ZIRP is often described as a wealth transfer from American savers to debtors. Because the shale industry is deeply in debt, these companies directly benefit from this arrangement.

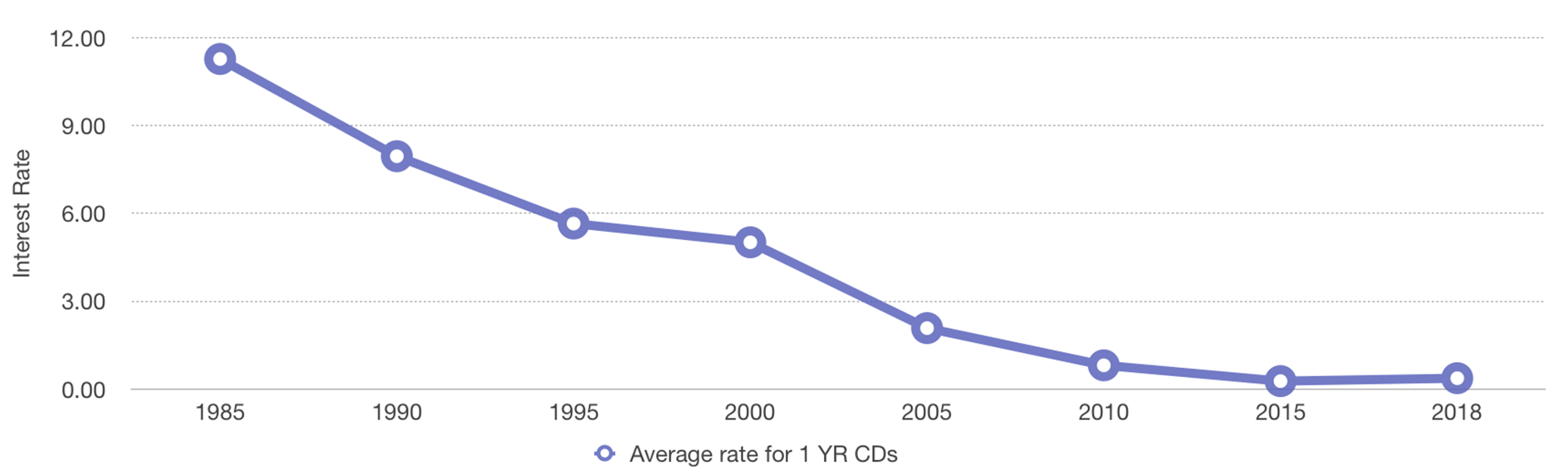

Below is a chart of rates for certificates of deposit (CD) since 1980 — historically a safe investment that gave people a decent return on their savings.

Data from Bankrate.com

Since 2010, if you put your money in a CD, you would not even be keeping up with inflation due to the low interest rate. That isn’t supposed to be how it works.

And as this next chart shows, historically that hasn’t been how it works. The graph below is the federal funds rate since 1950 (this is the interest rate that banks charge each other to lend excess cash overnight). It’s very clear that starting in 2008, the chart flatlined (due to ZIRP) and stayed that way for years — something that had not happened before.

Image: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

When that graph flatlined after the 2008 financial crisis, Americans’ personal savings stopped earning any meaningful interest.

ZIRP Policy Designed to Re-inflate Housing Bubble

While ZIRP has been devastating to retirees and other savers who would like to earn some interest on their money in the bank, it did manage to effectively re-inflate the housing bubble. Because even though you couldn’t earn interest on your savings over the last decade, mortgage rates have been historically low.

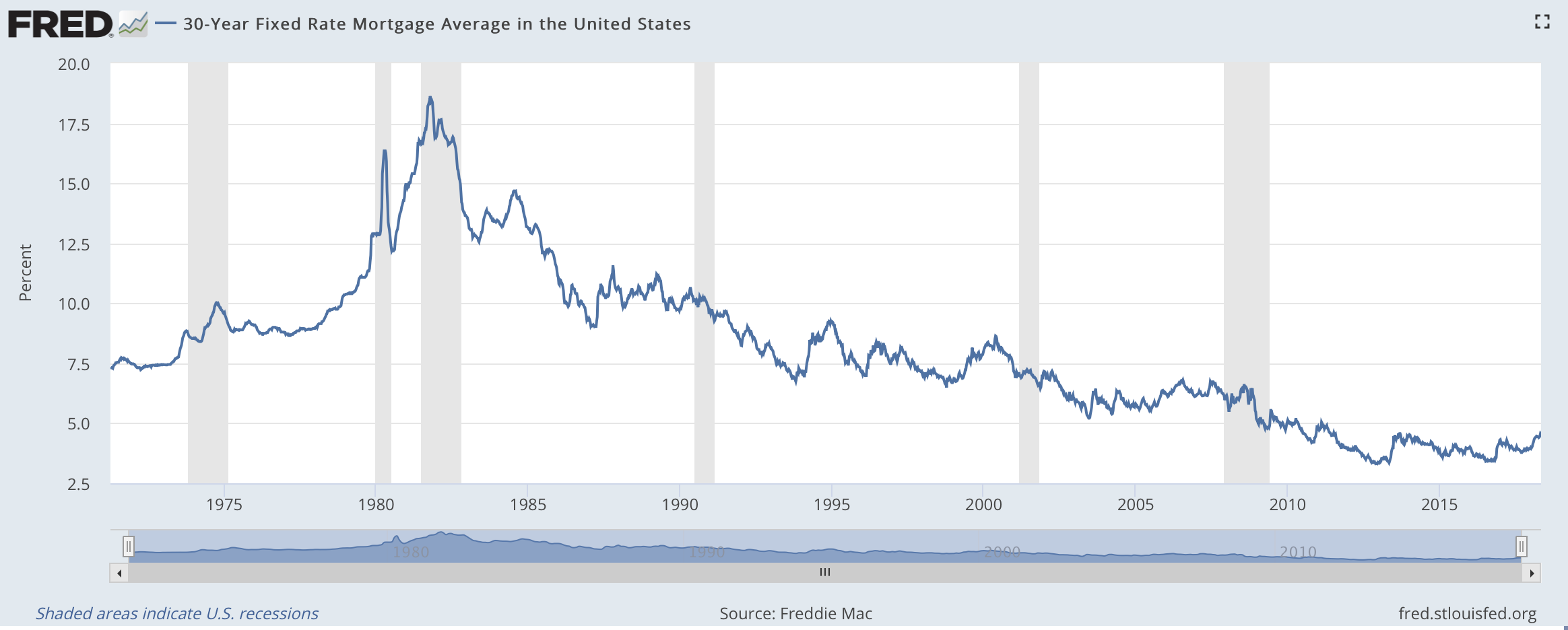

These low rates have kept people buying homes and refinancing. The chart below shows how ZIRP resulted in record-low interest rates for the 30-year fixed mortgage.

Image: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Once again, stories are emerging about overheated housing markets because ZIRP has gone on for so long. When it comes to the housing market, ZIRP certainly worked to re-inflate the market … and create new housing bubbles.

In response, the Fed is raising rates and promises more increases in 2018 and 2019, which has also begun to raise mortgage rates.

Bill McBride runs the economics blog Calculated Risk. He is widely acknowledged as someone who predicted the housing bubble and recovery. McBride’s track record is acknowledged in the title of this Business Insider article from 2012: The Genius Who Invented Economics Blogging Reveals How He Got Everything Right And What’s Coming Next.

McBride told DeSmog that ZIRP certainly helped the housing market. “With regards to ZIRP, the Fed’s QE [quantitative easing] policy pushed down long rates and that helped the real estate market recover,” he said.

Quantitative easing was another Fed program that helped big banks and is a tool used when interest rates are already at zero and thus can no longer be lowered.

The problem with trying to re-inflate one market is it tends to re-inflate all markets. It would be hard to argue that the stock market hasn’t been re-inflated as well by this policy. It has been on an epic run while the policy was in place.

And ZIRP has been instrumental in creating the American shale oil and gas industry and funding its epic money-losing streak during that same time period.

ZIRP Fuels Massive Borrowing in Shale Industry

There are two main ways that ZIRP has fueled the shale industry. One is that — unlike the rest of us not making money on our savings — big companies and investors have been able to borrow large amounts of money at very low rates. This is commonly referred to as “free money” during the ZIRP era because if you are paying little-to-no interest on a loan it is effectively free. This relationship was first detailed on DeSmog in 2014.

How much “free money” are we talking about? According to Helen Thompson’s book Oil and the Western Economic Crisis, the numbers are big:

“QE and ZIRP hugely increased the availability of credit to the energy sector. ZIRP allowed oil companies to borrow from banks at extremely low interest rates, with the worth of syndicated loans to the oil and gas sectors rising from $600 billion in 2006 to $1.6 trillion in 2014.”

Would you like to borrow a trillion dollars at extremely low interest rates? Sure you would. But you don’t get to — unlike the shale industry.

The second main way that ZIRP has funded the shale “revolution” is via the junk bond market. Junk bonds are bonds issued by companies — witih help from investment banks that get their cut — that have credit ratings below “investment grade.” To be an investment grade bond requires a certain level of confidence the company will pay back both the interest and principal on the bond “through good times and bad.”

Because there is a lower chance of a junk bond issuer being able to pay back interest and principal, those bonds reward investors with the promise of higher returns. If the company does well, the investors are paid well for their gamble. If not … they lose out because they invested in “junk.”

Just like the average person who is making no interest on savings, there are massive investment companies that need to provide clients with consistent returns.

There was a time when this was easy. Want a 4 percent return? Put it in a money market or CD rate that guarantees 4 percent. Done.

However, in a ZIRP environment, that isn’t an option. So investors must choose riskier assets like junk bonds to (hopefully) get a “traditional” return (aka yield), as junk bond investor Lawrence McDonald explained to CNBC:

“The market is thirsting for yield and the Fed is pushing people to do things like this. So big asset managers are reaching, reaching, reaching and companies know this and are issuing, issuing, issuing all this crap.”

“Crap.” Like junk bonds for shale oil companies that have never made money. But Wall Street keeps working with these companies to issue this “crap” and big asset managers keep buying it up, as Wolf Richter noted on Business Insider in 2015:

“Time and again, despite the collapsed prices of oil and gas, the players in the shale revolution have gotten more funding from Wall Street, whose ZIRP-blinded clients kept gobbling up the newly issued junk bonds, leveraged loans, and shares, taking on huge risks and hoping to make a little extra money in a Fed-laid minefield where all decent assets are way overpriced.”

ZIRP has been very, very good to the shale industry and Wall Street, as The Economist has noted:

“Low interest rates make it easy for shale firms to borrow, and fee-hungry banks cheer on the spectacle.”

And it is a spectacle. While the shale industry has lost over a quarter trillion dollars, it has been rewarded for this behavior.

As DeSmog explained earlier in this Finances of Fracking series, Wall Street is happy to loan cash to money-losing fracking companies because banks and investment firms make their money by making loans or selling junk bonds and collecting the fees on those deals.

Because shale companies have never made a profit, they must keep doing what they have always done — that means borrowing more money to drill more wells, which have been costing more money than they make. If shale companies stopped borrowing, they would have to either drastically reduce the amount of oil being produced, or likely have to declare bankruptcy — as many shale companies have done.

Fed Raising Rates: Is This the Beginning of the End for Shale Financing?

The Federal Reserve Building in Washington, D.C. Credit: AgnosticPreachersKid, CC BY–SA 3.0

ZIRP is slowly ending. The Fed has raised rates and has promised to continue raising rates through 2019.

That isn’t good news for the shale industry that will now need to refinance all of its loans at higher rates. But as in all good bubbles — and despite the warning signs — the oil industry is brimming with optimism in 2018. And the Wall Street money keeps pouring in at record levels, with plenty of buyers still eager to snap up these junk bonds.

According to Bloomberg, “Junk-rated energy companies were able to fund a record $9.25 billion of issuance in January.”

But despite the record-setting pace of junk bonds for energy companies, plenty of people are now warning of the problem (or crisis) that the Fed raising interest rates will create for the junk bond market and the shale industry. The problem was summed up quite well by the sub-title of this Seeking Alpha article: “Fed tightening affects junk bond prices negatively.”

How negatively? Financial data company Pitchbook recently highlighted some of the risks based on information from the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research (OFR), which says that the financial risk of interest rate increases is at an all-time high. “Just a 1 percent rise in interest rates would result in $1.2 trillion in losses from the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index — with even larger losses when one includes ‘junk’ high-yield bonds,” reported Pitchbook.

A return to even the historically low federal fund rates in the 5 percent range — where they were just before the financial crisis of 2008 — would be devastating to the junk bond market and the shale industry — as well as all of the asset managers who currently own this junk.

Pitchbook notes that the OFR says “the risk of a turnaround in interest rates are now higher than the ‘bond massacre’ in 1994 that drove Orange County, California, into bankruptcy and ignited Mexico’s peso crisis.”

It’s important to keep in perspective that even major shale oil companies like Continental Resources haven’t been able to pay the interest on the money they already owe at these historically low rates, a point that holds true throughout the industry. Companies have been borrowing money to pay interest on the money they have already borrowed.

Full Speed Ahead … Towards a Wall of Debt and Higher Rates

The movie (and book) The Big Short features several investors who all saw the housing bubble for what it was and then bet against Wall Street and the bad debt that was fueling the housing bubble. They were right and eventually made billions. However, they spent years knowing they were right but watching the housing bubble continue.

Ivy Zelman, a housing-market analyst at Credit Suisse, was one of the people who identified the housing bubble early on, and she notes that while it was clear there was a problem, it wasn’t clear when the reckless financial behavior would end.

“It wasn’t that hard in hindsight to see it,” Zelman said. “It was very hard to know when it would stop.” This sentiment echoes the famous Wall Street axiom: “The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

Much like the housing bubble, the shale bubble has gone on much longer than expected (by some). Of course, that just means that the industry is in a lot more debt than in 2014 when people first started warning about this issue. If things go bad now, they will go much worse than in 2014.

In 2014, Ivan Sandrea, a research associate at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, posed this question:

“Who can, or will want to, fund the drilling of millions of acres and hundreds of thousands of wells at an ongoing loss? The benevolence of the U.S. capital markets cannot last forever.”

While an industry that has never made money and is deep in debt cannot last, it can go on longer than expected. Just like the housing crisis did.

Even Wilbur Ross, currently the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, was warning about the shale debt problem in late 2015. He pointed to two specific problems: rising interest rates and the “wall” of debt coming due starting in 2018.

Ross told CNBC that companies were “running out of time” because “you have a wall of maturities starting in 2018, building up through 2021 [and] 2022.”

And here we are: in 2018 with rising interest rates and the shale industry piling on record levels of new debt via junk bonds while facing a wall of debt.

In January, William White, the Swiss-based head of the OECD’s review board and ex-chief economist for the Bank for International Settlements, commented in The Telegraph on the impacts of ZIRP and “free money.”

“Nine years of emergency money has had a string of perverse effects and lured emerging markets into debt dependency,” White said.

Sounds like an accurate description of the last nine years of the shale industry. But that wasn’t all White had to say: “All the market indicators right now look very similar to what we saw before the Lehman crisis, but the lesson has somehow been forgotten.”

It looks like the shale industry and the investors who funded it are poised to re-learn those lessons. However, as we know, Wall Street will prosper no matter what happens.

The question that remains is who will pay to bail out Wall Street and the shale industry if the bubble pops?

If history is any indication, it will be the same U.S. taxpayers who haven’t been making interest on their savings for the last nine years.

Follow the DeSmog investigative series: Finances of Fracking: Shale Industry Drills More Debt Than Profit

Main image is a derivative of “Oil Well Pump Jacks” by Richard Masoner used under CC BY–SA 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts