This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

According to climate scientists, limiting the worst impacts of climate change means weaning the world off of fossil fuels, not ramping it up. But two factors, the U.S. “fracking revolution” that helped boost domestic oil and gas production to record levels combined with lifting the 40-year-long ban on exporting crude oil in 2015, are complicating that vision.

In June, the United States displaced Saudi Arabia as the top exporter of crude oil, a stunning development for a country that only started exporting crude in 2016. That month, the U.S. exported over 3 million barrels of crude oil per day. To put that in perspective, the U.S. consumed 20.5 million barrels per day in 2018. That means that each day, the U.S. was pumping out of its borders a volume of oil equivalent to about 15 percent of its 2018 daily consumption.

Prior to the lifting of the crude oil export ban, which took effect in 2016, certain exports (mostly to Canada) were allowed.

This expansion can be directly linked to the production of oil via hydraulic fracturing (aka fracking) that has driven the U.S. oil production boom over the past decade. In addition to driving U.S. crude oil expansion, this much-lauded “fracking revolution” also was responsible for essentially the entire increase in global oil production last year, when the U.S. contributed 98 percent of that increase.

Without the shale boom, the world would likely be facing much higher oil prices and the potential for stagnating or even declining production (aka peak oil), both of which would help to hasten the needed energy transition to mitigate climate change.

While the Trump administration is rolling back regulations for the oil and gas industry and doing all it can to expand oil and gas production and exports, the crude export ban reversal and the fracking boom all happened under the Obama administration. And the oil industry is only too happy to highlight that point.

What do both sides of the aisle agree on? There’s bipartisan leadership support for the expansion of U.S. #oilandgas. It’s key to energy security and doesn’t mean we have to choose between our environment and our economy. https://t.co/l933l5bLft

— Chevron (@Chevron) September 17, 2019

Analysts predict that exports will continue to expand quickly.

“It will be 4 million barrels a day by six or eight months. Four million barrels a day is a lot bigger than the North Sea as a whole. That crude oil is going to go everywhere. It goes to Asia, Europe, to India,” said Edward Morse, Citigroup’s global head of commodities research, as reported by CNBC.

U.S. Exports of Liquefied Natural Gas Flooding the Globe

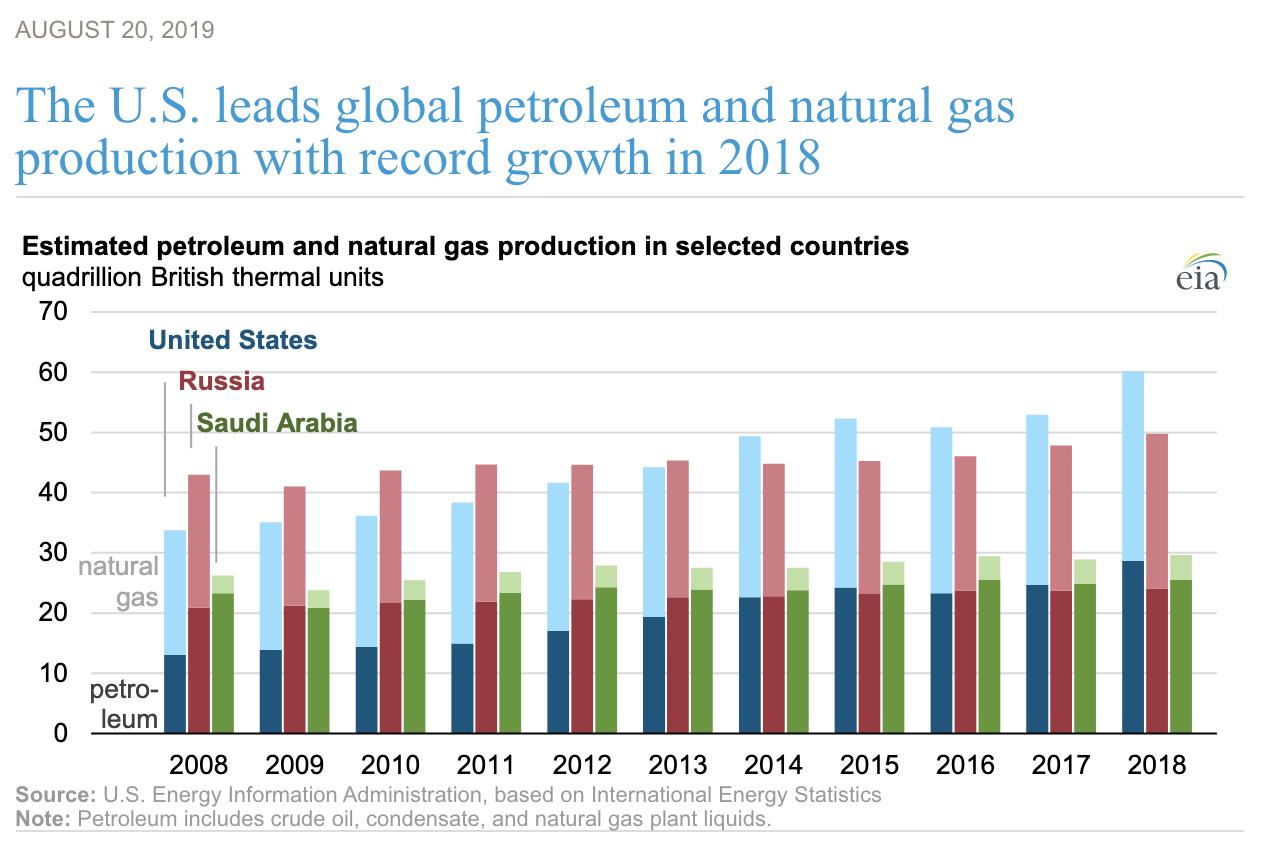

In addition to record U.S. oil production, fracking has yielded record levels of natural gas in the U.S. That has led to a rapid ramp up of exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG), following a similar trend as oil. In 2018, the U.S. became the world’s leading producer of both oil and natural gas.

The U.S. did not start exporting LNG until 2016, but since then, the volume of exports has taken off. With the fracking-induced glut of natural gas in the U.S., the oil and gas industry is investing heavily in expanding LNG export facilities.

The industry likes to tout natural gas as a climate-friendly energy solution (calling it a “bridge fuel” to renewables), but that concept has been thoroughly debunked, particularly as the price of clean energy and storage has dropped.

During Climate Week in New York City, industry CEOs will once again be pushing this idea as world leaders gather at a UN summit to discuss climate action.

#oilandgas flimflam men are lying! Journalists should not repeat the lies!

They want the public to believe that natural gas is a solution for #climatechange.

IT IS THE PROBLEM.

U.S. GHG emissions are rising not decreasing as flimflammers claim. 1/4https://t.co/bxG8bhIdPj pic.twitter.com/gDIV9nTH5Z

— TXsharon (@TXsharon) April 2, 2019

Flaring and Venting Are Climate Killers

Another result of the fracking boom has been a huge increase in the U.S. industry flaring and venting (burning and releasing) natural gas, which is primarily the greenhouse gas methane.

“This recent increase in methane is massive,” said Cornell professor Robert Howarth, the author of a recent study linking fracking to a spike in atmospheric methane. “It’s globally significant. It’s contributed to some of the increase in global warming we’ve seen and shale gas is a major player.”

Methane is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over the short-term, and the fracking industry in the U.S. is contributing to increased methane releases. At the same time, the Trump administration has proposed rolling back federal rules designed to reduce methane leaks and emissions.

With the current U.S. surplus, natural gas prices are very low and at times have gone negative in Texas. One reason for the oversupply is all the natural gas that is a byproduct of fracked oil wells. Record oil production has meant a corresponding rise in the accompanying natural gas.

In the booming oil fields of Texas and North Dakota that means producers often simply burn the natural gas or vent it directly into the atmosphere.

“If the public could see this, there would be no #fracking boom” – @TXsharon in @CalNBC’s investigation of #oilandgas #methane pollution in U.S. #1 oil producing region. WATCH: https://t.co/76k1GXDosq @MSNBC #dystopia #climatecrisis #climatestrike #Permian #cutmethane

— Mountainkeeper (@mountainkeeper) September 22, 2019

Methane is just one more climate-killing U.S. export.

Exporting Emissions and Climate Chaos

The transformation of the U.S. oil and gas industry due to fracking technology has been remarkable, leading to the country exporting oil and gas — and the related emissions — all over the globe.

While the current federal administration is full of climate science deniers, politicians of both parties are responsible for allowing this development at the very time the world needs to be rapidly reducing the amount of oil and gas being burned.

In December 2015, DeSmog reported on a forum at Columbia University’s Center for Global Energy Policy, where the topic was lifting the crude oil export ban — something strongly supported by all of the speakers at the event.

At the forum, Trevor House of the Rhodium Group summed up his thoughts on overturning the ban and the resulting impact on the environment:

“I’m of the view that we can have our cake and eat it too. It is possible to support domestic oil and gas production and meet our long-term climate objectives at the same time.”

That was magical thinking then, and now almost four years later, the world is being flooded with U.S. oil and gas — making long-term climate objectives impossible to meet.

Main image: Roughnecks on a drilling rig in Greeley, Colorado. Credit: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, public domain

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts