On March 5, there was a sense of drama and tension unlike in years past as ExxonMobil’s top executives gathered for their annual Investor Day presentation, a highly anticipated event where the oil major lays out its plans for the next few years in an effort to woo investors.

Long a darling of Wall Street, that day the oil major’s share price had fallen to a 15-year low. Battered by a volatile oil market and increasing scrutiny over the climate crisis, investors wanted answers on how Exxon planned on dealing with the shifting landscape.

“ExxonMobil is committed to being part of the solution,” CEO Darren Woods said. “We’re investing in new energy supplies to improve global living standards, working on technologies that are needed to reduce emissions and supporting sensible policies, such as those putting a price on carbon or regulations to reduce emissions of methane.”

Beneath that rhetoric is a bitter reality: Exxon flares more gas than any other company in the Permian Basin, America’s most prolific oil field, emitting massive volumes of greenhouse gases as well as toxic pollution that fouls the air in West Texas. The oil giant’s long history of funding climate science denial has given way to a craftier position of pledging support for climate goals while leaving an aggressive drilling and growth strategy mostly unchanged.

Signs warning of poison gas in Winkler County, Texas. Credit: Justin Hamel © 2020

On Investor Day, Exxon had another problem. Falling oil prices had cut into the company’s profitability, raising red flags about heavy spending.

Here, too, Exxon tried to couch its growth strategy in measured terms to appease investors demanding restraint. “We are adjusting our execution pace” because of the “current business environment,” Neil Chapman, the head of Exxon’s upstream unit, told investors, acknowledging the fall in oil prices. Some in the trade press interpreted the new strategy as a “slowdown” in the Permian Basin.

However, while Exxon tweaked its spending plans and drilling pace a bit, the overall strategy remained the same. Despite deciding to deploy fewer rigs, Exxon plans to spend $30 to $35 billion each year through 2025 and aims to produce 1 million barrels per day in the Permian by 2024. Both of those metrics are unchanged from the company’s prior guidance. Exxon is “leaning in to this market when others have pulled back,” as Woods put it.

Oil prices have declined, but “the longer-term horizon is more clear,” Woods said. The oil major expects oil demand to continue to rise indefinitely, warranting ongoing drilling at an aggressive rate.

Less than 24 hours after Woods’ comments, the oil market went into a tailspin. The spread of the coronavirus and the onset of an OPEC price war sent oil prices careening down to multi-year lows. The downturn will likely force cutbacks in drilling, somewhat reducing the scourge of flaring in West Texas. But based on Exxon’s long-term plans, the reprieve may only be temporary.

Flaring in the Permian

The surge of fracking in the Permian has resulted in a massive increase in oil production, but also a spike in flaring, or the burning of gas from oil wells, as drilling has outpaced the construction of natural gas pipelines. The Permian Basin saw flaring and venting, the release of unburned gas, largely methane, directly into the atmosphere, jump to 810 million cubic feet per day in 2019. That means that the volume of gas burned each day exceeded the amount of gas consumed in all of Texas’ households.

Even the industry admits that rampant flaring has become a major problem for its reputation (a “black eye” for the Permian), and a number of reports in the past year have raised alarm about the role that gas plays in exacerbating climate change.

But the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the oil and gas industry in the state, has done almost nothing to rein in the practice of flaring. In 2019, the commission granted 6,972 flaring permits, and rejected none. In fact, by all accounts, the commission has not denied any of the 27,000 or so flaring permits over the past seven years.

An abandoned camp outside of Orla, Texas, is illuminated in by a gas flare four miles away. Ambient light from oil and gas operations in rural Reeves County, Texas, cast a twenty-four hour shadow. Credit: Justin Hamel © 2020

The permissive attitude reached absurd proportions last year when the Railroad Commission granted a permit to Exco Resources, a shale driller that wanted to flare its gas even though it had access to a pipeline, simply because the company didn’t want to pay the fees to ship the gas. It was cheaper to burn the gas, and the Texas regulator gave the go-ahead.

The pressure on Texas has grown tremendously over the past year, as rampant flaring becomes increasingly indefensible. Under mounting pressure, Texas Railroad Commissioner Ryan Sitton released a report on flaring in February. While he is supposed to regulate the industry, he has consistently been one of fracking’s most powerful champions in the state.

Publicly available flaring data is scarce in Texas, so Sitton’s flaring report offered some useful information, even as he praised the benefits of fracking. For instance, the number one source of flaring over a 12-month period through October 2019 was XTO Energy, which flared 23,350 million cubic feet of gas per day.

XTO is a subsidiary of ExxonMobil.

The Permian’s Toxic Air Pollution

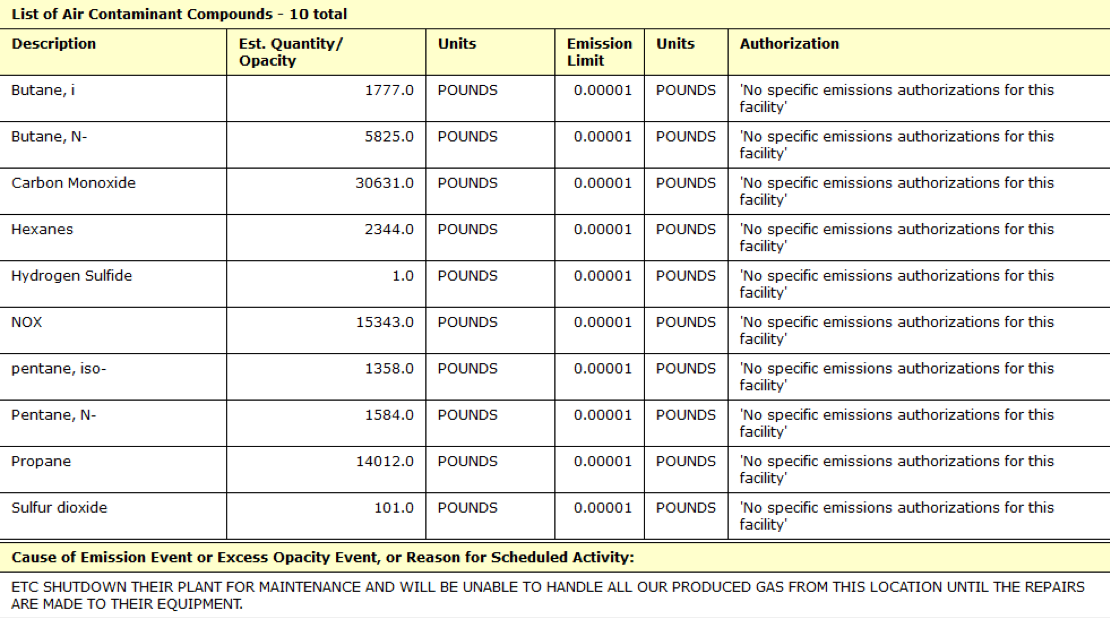

In August 2019, a pipeline in Midland, Texas, owned by a company called ETC had to shut down for repairs. XTO Energy sends gas from some of its Permian wells to that pipeline, so the shutdown presented the company with a problem. With nowhere to put the gas coming out of the ground, XTO decided to burn it. Because of the pipeline outage, XTO flared gas for 91 hours, according to an event report filed with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

Not only did XTO release an unknown volume of CO2 and methane into the atmosphere — the company is not required to report those volumes — but the flaring event also resulted in the release of more than 15,000 pounds of nitrogen oxides, 30,000 pounds of carbon monoxide, and 100 pounds of sulfur dioxide, among other contaminants.

Screenshot from TCEQ submission by XTO Energy

The incident highlights how venting and flaring is not just a climate problem. Flaring often results in the release of other toxic air emissions. ExxonMobil is far from the only culprit; the entire region has a problem with unpermitted pollution from oil and gas drilling.

A 2019 report from the Environmental Integrity Project found that between 2014 and 2017, roughly 35 percent of Ector County, which includes Odessa, “experienced sulfur dioxide air pollution levels in excess of the federal health-based standard.” That included hundreds of individual incidents of illegal releases of sulfur dioxide. Drilling activity has only increased since then.

Sulfur dioxide can contribute to respiratory problems and make breathing difficult, more so for young children and for people with asthma, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Nitrogen oxides can contribute to smog formation.

Despite the worsening air quality, the region only has three air quality monitors, and only one for sulfur dioxide, compared to around 60 monitors in the Houston area. That makes it difficult to obtain accurate and timely information.

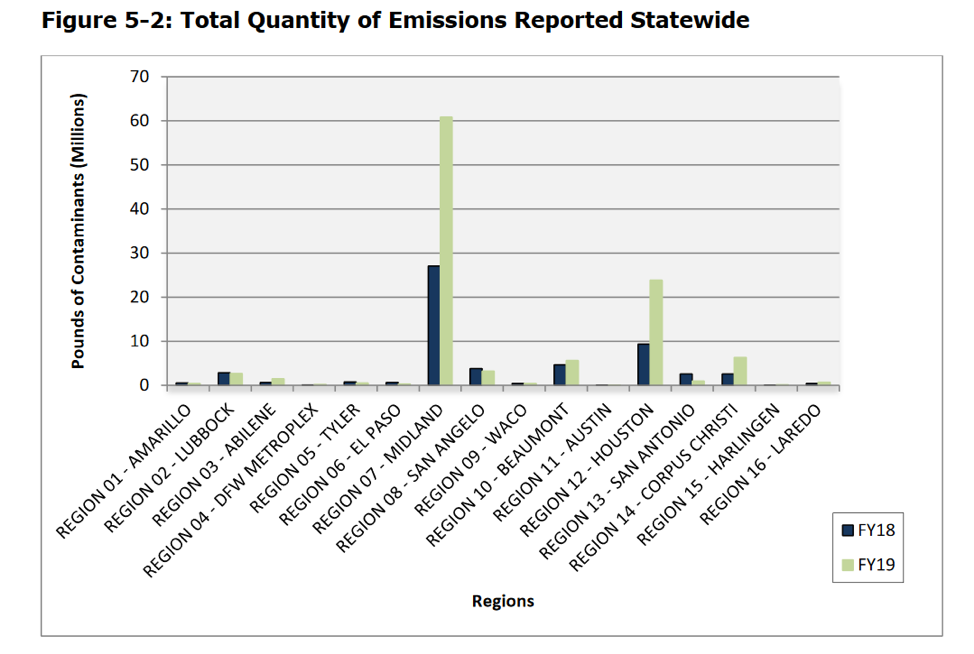

Nevertheless, according to data from the TCEQ, the volume of unauthorized emissions of air contaminants — emissions above an allowed threshold, due to an accident, blowout, or other unplanned event — surged in fiscal year 2019, with an enormous increase in Midland. More than 60 million pounds of emissions of air contaminants occurred in FY19 in the Midland region, up from less than 30 million the year before. The increase, the TCEQ said, was “primarily due to heightened oil and gas operations in the Permian Basin.”

Chart showing regional air pollution totals across Texas. Credit: TCEQ Annual Enforcement Report

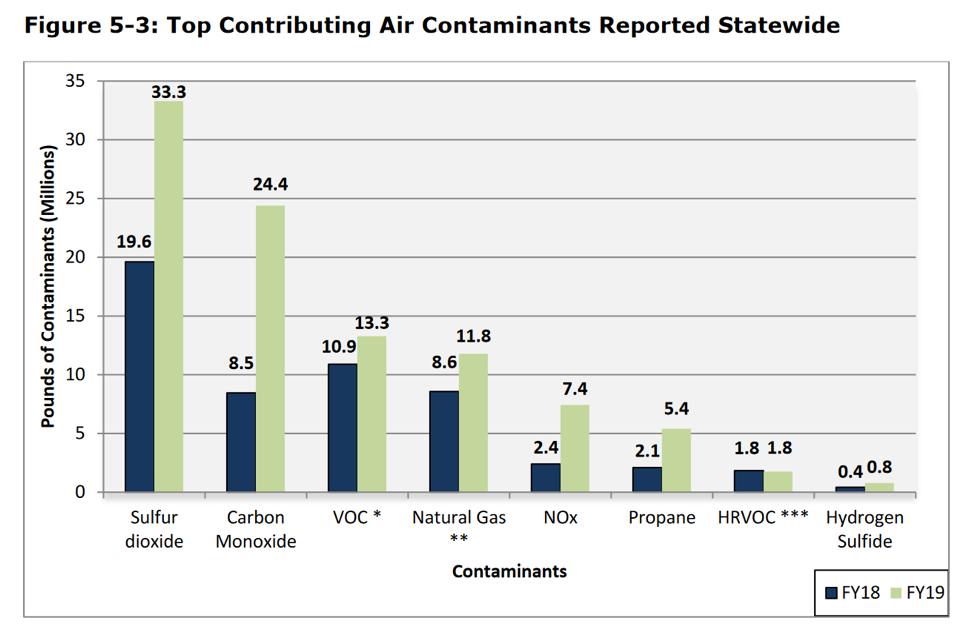

Chart showing showing top air pollutants reported statewide in Texas. Credit: TCEQ Annual Enforcement Report

But even that might be understating the impact since the data comes from the companies themselves. “The operator estimates emissions based on standard guidelines set by EPA and the duration and magnitude of the release,” Gunnar Schade, Associate Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at Texas A&M University, told DeSmog. “Such estimates are at times crude and inaccurate, but it’s the best we have in most cases.”

“But since this cannot be policed, I think it is fair to assume that ‘uncertainty’ cuts mostly one way, towards underestimation,” Schade added.

In a more significant incident in early February, drillers in the Permian Basin flared a massive amount of gas because of a winter storm. Power failures led to the temporary shutdown of several natural gas processing facilities, so multiple drillers resorted to flaring, emitting around 8.8 million pounds of air pollution, according to advocacy group Environment Texas. The release over just two days in February was equivalent to about one quarter of the pollution released in the region in all of 2018.

ExxonMobil’s Permian Plans on Thin Ice

Shale drilling has slowed recently because of profound financial stress. As small and medium-sized drillers pull back, the oil majors have taken over. With deeper pockets, the majors can preside over loss-making fracking operations for years.

At its Investor Day in New York in early March, Exxon showed little sign of slowing down. Exxon is “pursuing a strategy that is destructive of both shareholder value and the planet,” Edward Mason, head of responsible investment at Church Commissioners for England, who attended the company’s investor meeting, told Reuters.

However, the most recent collapse in oil prices — with one measure, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) falling to the low-$30s — could be so painful, that even a company the size of Exxon might think twice. Chevron has already admitted that it might cut spending in response to the sudden Saudi-Russia price war. Exxon too might soon have to slam on the brakes.

Main image: Flare in the Permian Basin of West Texas. Credit: Justin Hamel © 2020

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts