This story is a part of Covering Climate Now’s week of coverage focused on Climate Solutions, to mark the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. Covering Climate Now is a global journalism collaboration committed to strengthening coverage of the climate story.

Shell recently announced plans to “stop adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere by 2050,” a move hailed by some as a major step towards addressing climate change. Around the same time, however, the oil and gas major confirmed it would go ahead with its investment in a joint $6.4 billion gas project in Australia.

This approach of saying one thing about addressing climate change while doing the opposite has been standard practice for the oil and gas industry for decades. Another popular strategy for the industry is to push certain climate “solutions” — often with slick advertising campaigns — that sound good in theory but are not viable in practice.

A handful of engineering and policy professors, writing recently in Foreign Affairs magazine, promote several of the industry’s go-to ideas, such as decades’ old favorites like carbon capture and the fallacy of natural gas as a climate-friendly fuel.

This article is a great example of framing climate change as primarily a technological problem, with studious ignorance of history/politics – a misdirecting frame helping Big Fossil.

This particular piece also has a number of misleading tropes. Worth analyzing in depth! (Thread) https://t.co/JGIazhLOJl

— Ben Franta (@BenFranta) April 19, 2020

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS)

In the year 2000, several major oil and gas companies, including Shell and ConocoPhillips, formed the Carbon Capture Project, whose goal is to help “develop next generation technologies that will reduce the costs of CCS and make CCS a practical and cost-effective option for reducing or eliminating CO2 emissions, resulting from the use of fossil fuels.” Carbon capture centers on the idea of pulling carbon dioxide out of smokestacks that are burning fossil fuels and then injecting it deep underground for permanent storage.

The project’s website boasts of “more than 150 projects” that advance the understanding of CCS and says carbon capture is “now accepted as an appropriate emissions reduction technology to help address the challenge of reducing CO2 emissions while the world develops alternative energy sources.”

However, Carbon Capture Project’s latest phase has just three participating companies (BP, Chevron, and Petrobras), puts out a couple publications a year, and sports a website design that looks straight out of 2008. In the meantime, alternative energy sources such as wind, solar, and battery storage have become cheaper than coal power and often compete on cost with natural gas power.

More up-to-date initiatives focused on carbon capture and backed by oil and gas companies do exist, such as the Carbon Capture Coalition, which is a 2018 rebranding and expansion of the National Enhanced Oil Recovery Initiative. Enhanced oil recovery is a current industry practice that injects carbon dioxide into aging oil fields to squeeze out more oil. Yes, more oil.

It also, incidentally, represents the only carbon capture technology that exists at scale. While enhanced oil recovery does manage to sequester most of the injected CO2 permanently, carbon dioxide harvested from human sources (rather than natural reservoirs) represents only 15 percent of what the industry currently uses.

Last year, ExxonMobil released a video ad saying that “carbon capture is important technology” and “…if these industrial plants had technology that captured carbon like trees, we could help lower emissions.”

That is a big “if.” The company’s website claims “ExxonMobil engineers and scientists have researched, developed, and applied technologies that could play a role in the widespread deployment of carbon capture and storage for more than 30 years.”

In February, the Wall Street Journal reported on the efforts of Exxon, Chevron and Occidental to develop and implement carbon capture technologies that would directly scrub out CO2 from the air and turn it into a synthetic fuel that could be burned in a car or airplane. The New York Times reported on similar efforts in 2019.

However, decades earlier, Exxon itself was dismissing the viability of carbon capture and storage.

Last year, the Climate Investigations Center quoted former ExxonMobil CEO Lee Raymond explaining in 2007 that implementing carbon capture on an industry-wide scale was not economically or even technically feasible.

“[I]t is a huge, huge undertaking,” Raymond reportedly told the audience at the 2007 National Petroleum Council event, “and the cost is going to be very, very significant.” Raymond also said that carbon capture and sequestration technology “has never been demonstrated at scale.” One of the things Raymond highlighted was that even if a company managed to capture all of the carbon dioxide produced by burning fossil fuels and suck even more out of the atmosphere, storing, or sequestering, that carbon dioxide represents another huge challenge.

A challenge that the scientists at Exxon had been aware of, and not too keen on, since 1981.

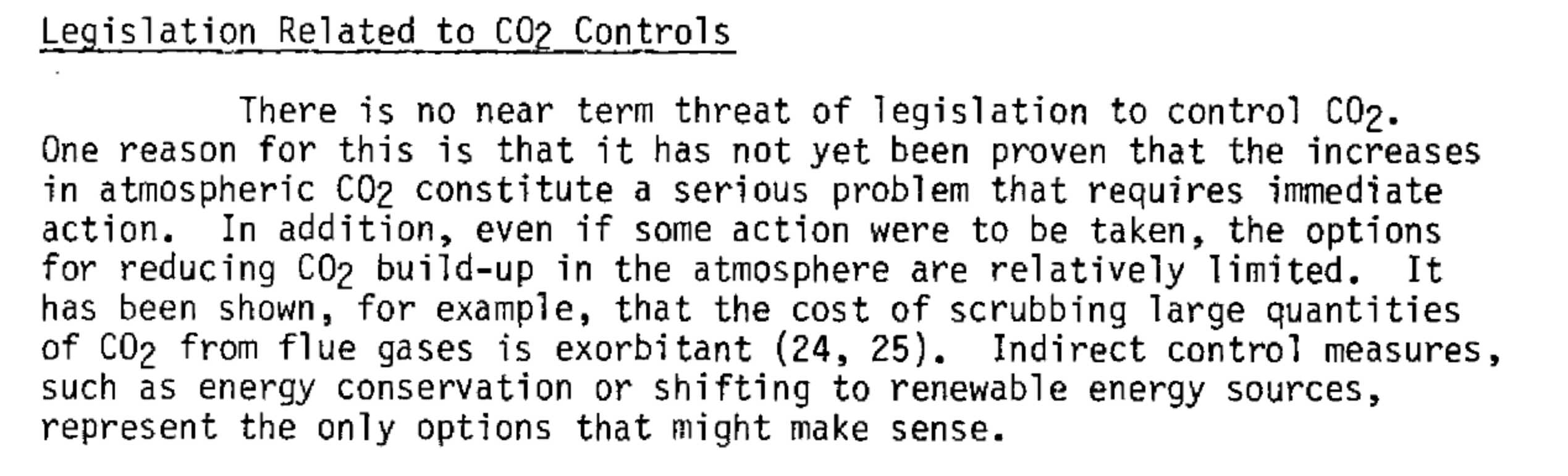

In an Exxon Research document described as the Atmospheric CO2 Scoping Study that was published in 1981, the company reached a conclusion that still holds true almost 40 years later:

“It has been shown, for example, that the cost of scrubbing large quantities of CO2 from flue gases is exorbitant. Indirect control measures, such as energy conservation or shifting to renewable energy sources, represent the only options [under CO2 control legislation] that might make sense.”

From the Exxon Atmospheric CO2 Study

Exxon knew that the costs of scrubbing large quantities of carbon dioxide from smokestacks were exorbitant in 1981 and that remains true in 2020. While implementing primarily aggressive energy conservation 40 years ago would have made sense, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded in 2018, the only way to keep global heating at 1.5 degrees C requires shifting to renewable sources for the majority of power and electrifying and making more efficient energy use.

Carbon capture was the coal industry’s plan to remain relevant in a carbon-constrained world. That has been a colossal failure. No reasonable people are touting that concept anymore and the coal industry today looks like a money-losing disaster. The “most efficient” coal plant in America just went bankrupt for the second time.

The same is true for oil and gas. Again, renewable power is already cost competitive with natural gas, and that’s without natural gas power plants having to invest huge sums in carbon capture, which would increase the cost at a time when renewable power costs continue to fall rapidly. Even the oil and gas industry is turning to renewables for power generation.

It is no surprise that the oil and gas industry is still pushing carbon capture as its answer to the climate crisis, but what Exxon concluded in 1981 is even more true today: The costs are exorbitant and renewables are the real answer.

Stanford University professor Mark Z. Jacobson makes the case in the Wall Street Journal’s February article on carbon capture. “There’s really no case ever where carbon capture is better than just taking renewable energy and replacing a coal or gas plant,” he said.

The Fallacy of Natural Gas

Another of the oil and gas industry’s favored approaches to the climate crisis is selling natural gas as clean energy. This stance again proposes that continued burning of fossil fuels is a climate solution.

As we have documented on DeSmog, the oil and gas industry’s leading lobbying group, the American Petroleum Institute, has been running an ad campaign promoting natural gas as clean energy and a way to reduce climate emissions.

From an American Petroleum Institute video advertisement.

However, we now know that natural gas can be as bad for the climate as coal due to all of the associated methane emissions that come with producing and distributing the gas. Natural gas is approximately 90 percent methane, a potent greenhouse gas and major contributor to climate change.

And last week, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released preliminary data showing that atmospheric methane levels are at an all-time high and increasing rapidly. Oil and gas production are a major source of methane emissions and the Trump administration removed Obama-era regulations designed to limit these emissions.

The methane problem is something the industry has known about for a long time.

Exxon engineers wrote a chapter in the book Engineering a Global Response to Climate Change, which was released in 1997 and clearly acknowledged that “methane is produced by activities associated with energy production (e.g., coal mining and natural gas production and distribution)” among the fundamental sources of greenhouse gases.

From Engineering a Global Reponse to Climate Change

Once again the industry has known about natural gas’s methane issue for decades but this is missing from its current ads promoting the fossil fuel’s climate credentials.

In 2006, representatives of the industry gathered in Washington, DC, to discuss how to sell natural gas as a climate change solution.

Cover from “Natural Gas as a Climate Change Solution”

The summary report for this meeting lays out the industry strategy for replacing coal with natural gas, but once again notes that without carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology, natural gas is “insufficient” as a climate solution, meaning it would have to be “replaced with non-carbon energy sources.” As the report says:

“On a path towards stabilization in such analyses, decreasing coal use while increasing natural gas is expected to be an effective strategy through the emission peak. Following the peak, however, as emission reductions become more severe even these actions become insufficient and natural gas would have to be used in conjunction with CCS or replaced by non- carbon energy sources.”

The report, which was released before the fracking “revolution” of the past decade, also notes that methane is a powerful greenhouse gas and that emissions from oil and gas production are a real issue. This report further highlights the problematic issues of flaring (burning) and venting (directly releasing) methane during petroleum production.

Read more of DeSmog’s Covering Climate Now stories on Climate Solutions

Methane emissions are at record levels and in 2019 increased at one of the fastest rates ever. Flaring and venting of natural gas in the U.S. is a huge problem and contributor to climate change, blowouts at oil and gas wells produce massive methane leaks, the Trump administration has rolled back regulations, and Exxon is currently asking the industry to adopt its own voluntary regulations for methane.

The industry has been selling natural gas as a climate solution since at least 2006. Carbon capture was not a viable option in 2006 and it’s still not in 2020. But switching to “non-carbon energy sources” would represent a massive shift in oil and gas companies’ fundamental business model.

Carbon Taxes, Algae Fuel, and More

In 1991 Exxon subsidiary Imperial Oil calculated that a heavy tax on carbon — $72 per ton in today’s dollars — would be necessary to actually curb climate pollution from the companies producing those emissions. Nearly 30 years later, ExxonMobil is still putting its support (and occasional money) behind this idea, just at a much lower proposed price — only $40 per ton. Once again, decades of delay.

Another tactic employed by the oil and gas industry is placing advertising dollars behind niche ideas like biofuels made from algae. Despite hundreds of millions of dollars from venture capitalists poured into algae biofuel companies, the technology remains a pipe dream for decarbonizing the economy.

In 2017, GreenTechMedia found that “the few surviving algae companies have had no choice but to adopt new business plans that focus on the more expensive algae byproducts such as cosmetic supplements, nutraceuticals, pet food additives, animal feed, pigments and specialty oils. The rest have gone bankrupt or moved on to other markets.”

In 2019, however, Exxon was still prominently promoting its algae biofuel research.

We’re researching algae biofuel with about 40% of its mass as fat, which can be turned into fuel. The swish is just a nice bonus. #SoothingScience pic.twitter.com/Md7vGvcPWn

— ExxonMobil (@exxonmobil) July 8, 2019

The industry has also tried branding fracked gas as “sustainably fracked” and methane captured from cow manure as “renewable methane,” in an apparent move to justify maintaining natural gas infrastructure against the push towards electrifying home heating and cooking.

According to the Los Angeles Times, “Environmentalists say renewable gas has many of the same problems as fossil gas: It leaks from pipelines, adding a hard-to-measure climate cost. It can contribute to unhealthy air quality inside your home.

And it requires consumers to keep paying for the upkeep of aging infrastructure that has caused several costly disasters, including the deadly San Bruno gas pipeline explosion and the Aliso Canyon methane blowout.”

Shifting to Renewables

When Exxon’s engineers said in 1981 that shifting to renewables was one of the only options that made sense for controlling carbon emissions, it wasn’t a viable option. The cost to produce electricity with wind and solar was much higher than using coal or natural gas. Large-scale battery storage was just a concept. Electric cars and buses weren’t yet mainstream.

Now, however, all of those climate solutions actually are now viable and, in many cases, the cheapest option. Germany just produced half of its electricity from renewables. Wind power just produced more electricity than coal did in the U.S. Large scale battery storage is making the need for gas peaker plants obsolete.

Something that would have seemed impossible a couple years ago…

Wind generated more electricity nationally than coal on April 12. That’s not wind, solar and hydro. Just wind. On its own. pic.twitter.com/FVOFDU2P4k

— Ben Storrow (@bstorrow) April 19, 2020

The oil and gas industry has spent huge sums of money misleading the public about climate change and lobbying against climate policies. It has worked to effectively delay the real climate solutions the industry itself identified decades earlier, while pushing ineffective approaches that are compatible with continuing the world’s reliance on fossil fuels.

In 1981 Exxon engineers identified renewable energy and energy conservation as real solutions to curbing climate pollution. In 2006, the oil and gas industry knew that natural gas was only a partial solution if carbon capture technology was economically viable. We now know that solar and wind power are viable and carbon capture isn’t.

Experts have found that the world could decarbonize (and limit warming) by rapidly switching to renewable energy and electrifying transportation, heating and cooling, and industrial applications. Exxon knew this basic concept 40 years ago.

Now in 2020, those solutions are economically viable and already being scaled up globally, presenting perhaps the biggest existential threat the oil and gas industry has ever faced. The industry’s preferred climate solution, ultimately, seems to be dumping money into advertising false solutions that maintain the status quo.

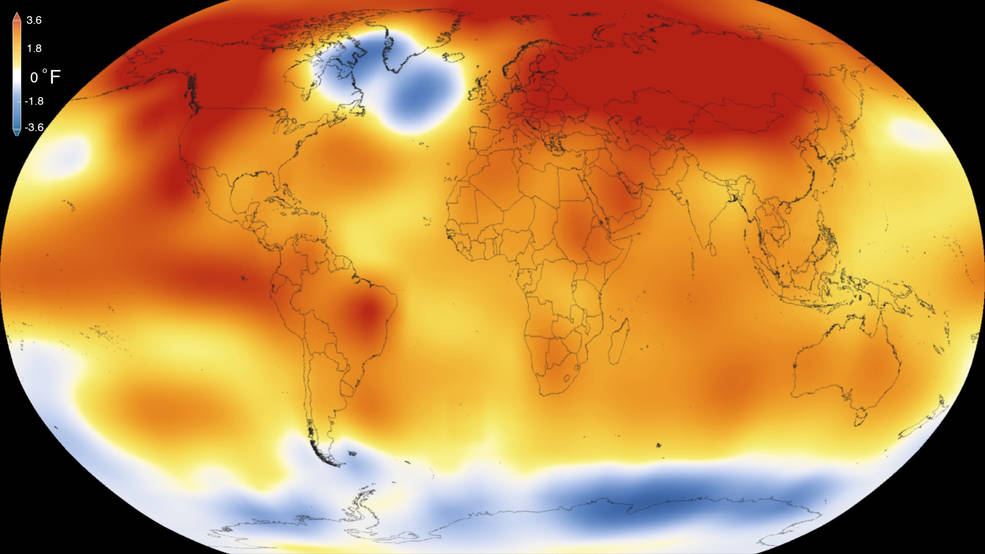

Main image: Analyses reveal record-shattering warm temperatures across the globe in 2015. Credit: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, CC BY 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts