Is the chance for a green recovery flying by?

Despite governments around the world claiming they want to support low-carbon industries in the wake of COVID-19, many have prioritised airlines and plane manufacturers for bailouts with no green strings attached — giving or lending money to some of the world’s biggest polluters.

With ongoing restrictions to prevent further spread of COVID-19, a major recession, and consumer concern about the impacts of flying increasing, the aviation sector has seen an unprecedented fall in demand worldwide. So airlines are asking for money to help them weather the bad times.

But with forecasts indicating it will be several years before demand returns to the profitable highs of 2019, could governments end up propping up an industry ultimately forced to downsize? And can governments support the industry in a way that satisfies a sustainable vision for the future of aviation?

A review by DeSmog UK of plans to save the ailing aviation industry, backed by interviews with aviation and climate experts, indicates that government bailouts are likely to fail to deliver a long-term vision for the sector that is compatible with emissions reduction targets — letting it off the hook for its contribution to climate change. The anaylsis finds:

- The sum of government bailout packages requested by the industry is unlikely to be sufficient to see companies through the crisis, with one estimate suggesting the money may only last for around 6 months;

- Where green strings have been attached to bailout packages, they either mirror existing commitments, are too unambitious to meet climate goals, or may be unenforceable;

- Governments are acting against the advice of leading economists that argue other, lower-carbon sectors are a better way to spend public money;

- Airlines’ calls for support based on their contribution to employment may not be viable in the long-term, and contrasts with recent support for their shareholders.

Propping-up polluters

Governments face a conundrum when considering aviation industry bailouts: how do they soften the fallout of the coronavirus on one of the world’s most polluting industries while also taking their climate commitments seriously?

The aviation sector was responsible for 2.4 percent of global fossil fuel carbon dioxide emissions in 2018 — around the same as Germany. The industry’s emissions in 2018 were 32 percent higher than in 2013. Non-carbon dioxide emissions from planes are rarely factored into emissions estimates but are thought to roughly double the sector’s overall climate impact. Overall, aviation emissions are projected to triple or more globally by 2050, just as the world needs to rapidly decarbonise to limit global temperature rise to 1.5C.

Like what you’re reading? Support DeSmog by becoming a patron today!

Despite some efforts to produce low emissions planes, there are limits to the currently available technology to help the aviation industry decarbonise. The sector has also been slow to implement measures to cut emissions. The International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), the UN forum where nations are responsible for addressing aviation emissions, has yet to set a long term climate goal, while a small group of countries at an ICAO council meeting last month agreed to weaken the baseline for its main global climate policy, an emissions offset mechanism called the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA).

As such, many experts believe demand reduction is needed to contain the sector’s rising emissions, particularly in the short term.

It’s against this backdrop that governments are splurging cash on the industry. From a purely commercial perspective, it’s clear financial support is needed for many airlines to survive. What is not obvious is how long this support will be needed, and if it can be made compatible with nations’ commitments to the Paris Agreement.

A lot hangs on how quickly demand for flying returns. Passenger numbers have plummeted since COVID-19 spread in early 2020. By April, nearly two-thirds of the world’s 26,000 passenger aircraft were grounded. Overall passenger levels were still down 91 percent in May 2020 compared to a year before, and while some domestic flights are now beginning to resume (especially in China), the global number of flights in early July was still down 60 percent compared to January.

Industry lobby group the International Air Transport Association (IATA) expects the sector to lose $84 billion this year — the biggest loss in its history, and three times the losses seen in 2008 after the financial crisis. Overall passenger levels in 2020 will sit at 2.25 billion, it said in June, down from 4.54 billion in 2019.

Several organisations have set out a range of recovery scenarios for the next few years (outlined in the table below). In July, Alexandre de Juniac, director general of IATA, stated that the industry was “only at the very beginning of a long and difficult recovery.” While estimates vary, an industry consensus is emerging that traffic will not return to 2019 levels for around three to five years.

United Airlines said it expects recovery to “plateau” near 50 percent until a vaccine is widely distributed, which is not likely for at least a year. IATA and Tourism Economics this week revised their baseline scenario for recovery to 2019 levels to 2023, up from 2022. In its new “downside” scenario, passenger levels still sit below 2019 levels in 2025.

Recovery will be influenced by the social and economic changes that occured before and during the virus outbreak, such as the flight shame movement, concerns over the health and environmental impacts of flying, rising unemployment and a major economic downturn. Paul Peeters, Professor of Sustainable Transport and at Breda University, says the number of overnight trips taken tends to correlate strongly with GDP per capita. In a downturn, aviation will likely be especially hard hit since trips taken by plane tend to be more expensive overall. IATA surveys have also shown a rising hesitancy to fly even when the pandemic has subsided, with more and more people saying they will wait at least six months.

The huge adoption of video conferencing software over the past few months could also fundamentally change ideas about the need for frequent business travel, a high contributor to airlines’ revenues. In a recent survey of the views of Fortune 500 chief executives, 91 percent said business travel will become less frequent, replaced by video conferencing. IATA has also said it expects corporate travel demand to be weak.

The huge impacts on the industry are why, in mid-March, IATA called for $200 billion in “emergency aid” from governments — an amount roughly equal to a quarter of the industry’s usual yearly revenue.

But even this amount of money would only last airlines around six months, estimates Tim Johnson from the Aviation and Environment Federation — a far shorter time than many project for the recovery. Further bailouts will likely depend on how the summer goes, says Johnson, noting airlines appear cautiously optimistic about Europe.

Aviation industry consultant ASM Global Route Development also concludes that further bailouts will be needed, saying in one report that major state assistance “will need to continue for some time to come”.

Green recovery?

In addition to asking for bailout cash, IATA warned in early July against “new regulatory or cost barriers to travel”. And many airlines have been quick to lobby against any so-called ‘green strings’ being attached to rescue packages.

But despite the impacts of the pandemic, tackling climate change is still a popular demand. A global poll in April showed two thirds of people globally think climate change is as serious as coronavirus.

Given the short timeframe available to address the causes of climate change, many view the need to attach green strings to bailouts as far more than “nice to have”. As Costa Rican diplomat and former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres pointed out, the current capital injection will define the shape of the economy for the next 10 years — meaning bailouts will need to be compatible with climate goals from the outset: “The big question now is what are the characteristics of the recovery packages going to be?” she said in April.

There has been much speculation on how and if green measures could be applied as part of bailout deals for aviation. One paper argued that conditional green bailouts for airlines could require achievement of net-zero emissions by 2050, as well as intermediate five or 10 year targets. “If airlines are unable to meet these targets, bailout funding would be converted to equity at today’s very low stock market spot prices,” it said. Others argue bailouts should be linked to airlines paying fuel tax.

Such conditions could be a chance to ensure that cheap air travel does not expand as it has after previous crises, which is a real risk, according to Jo Dardenne from NGO Transport and Environment (T&E). It is worrying that low cost carriers are calling for “price wars” to stimulate demand, she says: “We’ll get into an aviation market where you have bailed out and subsidised airlines, and low cost airlines that are competing to stimulate demand.”

She points out that after the 9/11 crisis and the 2002-2004 SARS outbreak, aviation traffic increased to higher levels than before. “We’re now at a risk where this could also happen after COVID, if potential climate conditions and strict regulations are not put in place to avoid aviation and traffic bouncing back to pre COVID levels.”

Source: Ipsos MORI Global Advisor, Earth Day 2020 poll

As of late May, governments around the world had committed $123 billion in financial aid to airlines. Only around half of this is loans due for repayment, with the rest in the form of wage subsidies, equity financing, tax relief and subsidies. In Europe alone, governments have agreed to deliver around €30 billion in bailouts to airlines.

Yet many airlines have lobbied against attaching green strings to this money, arguing that now is not the time for new environmental requirements. Partly as a consequence of this pressure, the vast majority of aviation bailouts delivered so far have had no green conditions, which campaigners argue simply supports the industry to keep polluting.

Two exceptions to this have been in France and Austria. The French government handed Air France a €7 billion bailout in May on the understanding that the airline set the goal of becoming the world’s “most environmentally-friendly” carrier. It also set requirements to halve carbon dioxide emissions per passenger and per kilometre against 2005 levels by 2030; halve overall carbon dioxide emissions from domestic flights by 2024; and source two percent of its aviation fuel from sustainable sources by 2025.

These conditions have been met with mixed reactions, however, with some climate experts sceptical about their climate impact. Pedro Piris-Cabezas, a Senior Economist at the Environmental Defense Fund, said he was surprised at the positive reactions to the announcement, since none of the conditions were particularly strong: The fuel and 2030 carbon targets had previously been announced, and Air France had previously outlined plans to overhaul its domestic routes, apparently linked to the €180 million and €200 million losses it posted in 2018 and 2019.

Following a public push, Austrian Airlines likewise saw conditions attached to its €450 million bailout. The airline agreed to eliminate all short-haul flights for which there is a rail connection of less than three hours and to reduce its total emissions by 30 percent in 2030 compared to 2005 levels. However, T&E says the 2030 emissions target is still too weak and it is also unclear if and how the target will be legally enforced.

There is also uncertainty over the effectiveness of the conditions attached to all-important sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs), lower carbon alternatives to petroleum jet fuels. IATA recently called for more investment in SAFs to lower their price and “help power aviation’s contribution to the post-COVID-19 recovery”. IATA has an industry commitment to reducing carbon emissions by 50 percent from their 2005 level by 2050 which is expected to involve SAFs. However, the industry as a whole has no clear target to significantly increase the use of the fuels in the short-term.

Dan Rutherford from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) notes that Air France’s two percent alternative fuel target, though small, would be “a significant increase in use” due to the tiny amounts used currently. But the sustainability framework for SAFs currently going through the EU does not consider indirect emissions and will continue to consider biofuels as zero emission fuels unless it is “substantially changed” before it is enacted in 2021, says EDF’s Piris-Cabezas. “With such poor-quality SAF it will be pretty easy and even inexpensive for Air France and Austrian airlines to meet their 2030 goals,” he argues.

There has been some recent movement from the industry on climate policies. In the UK, for example, industry group Sustainable Aviation recently committed to “net zero” emissions by 2050. The UK’s recently launched “jet zero” industry council also aims to make a zero emission transatlantic commercial flight possible within a generation, although environmental groups are treating the announcement with caution, and the UK government is also funding other green aviation projects.

Nonetheless, countries at the UN recently acquiesced on the industry’s request to weaken the main international climate measure for aviation, CORSIA, which is expected to delay requirements for offsets under the scheme for at least three years.

So, on the whole, “all of these bailout discussions show that the aviation sector is very quick to choose international solutions when they’re environmentally unambitious, and very quick to choose national measures when it comes to getting cash,” concludes T&E’s Dardenne.

Unsustainable business

Beyond the environmental impacts, there’s a real risk rescue package money may be used to bolster businesses that were destined to fail, given the aviation industry’s trajectory.

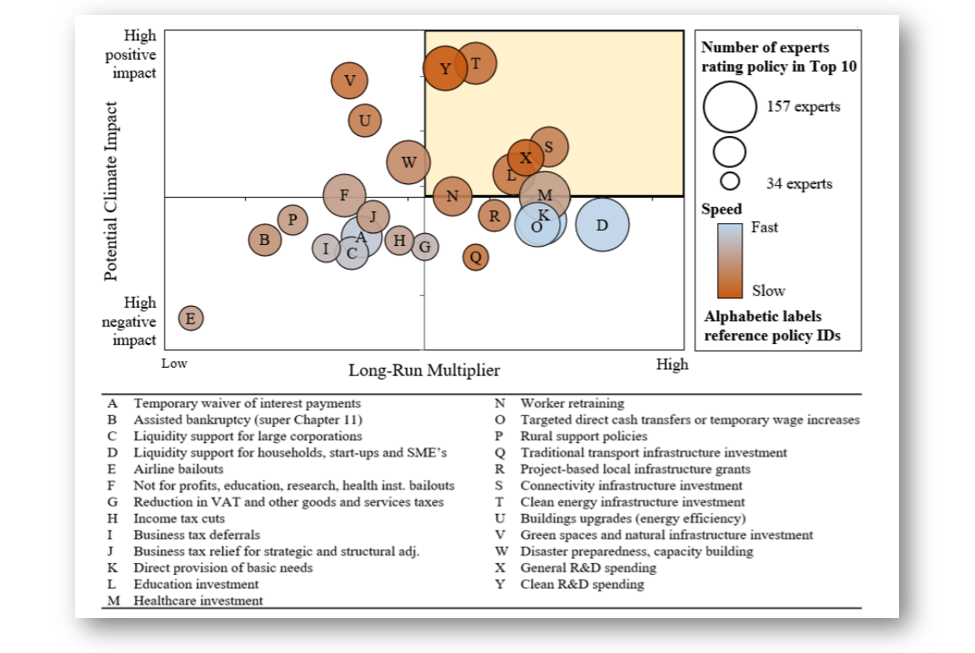

Many top economists think aviation bailouts are a bad idea for reasons other than being contrary to climate goals. In early May, a group of leading economists surveyed 231 high-level experts from around the world to ask their views on different stimulus policies. The paper found non-conditional airline bailouts to have the lowest perceived economic payoff and overall desirability: they featured in fewer experts’ top 10s than any other policy.

Image: Survey results of the relative benefits of different recovery package targets. Airline bailours are labelled ‘E’. Source: Oxford Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment | Working Paper No. 20-02

“Airline bailouts are an inefficient use of taxpayer money at a time when fiscal recovery (stimulus) spending is sorely needed,” the authors concluded, adding that any airline bailout should include conditions for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, with interim targets and a delivery plan. Though Chris Lyle, a sustainable aviation consultant, points out that the report may not fully incorporate the importance of foreign tourism for some economies.

Regardless of the bailouts, some investors have already signalled they are pulling out from the aviation sector. In May, American investor and business tycoon Warren Buffet sold all his stocks in airlines. Meanwhile, investments in airport expansions are plummeting. An analysis carried out by Construction News found as much as £1 billion of capital investment in UK airport expansion has been paused. Since March 2020, credit ratings agency S&P has lowered its debt ratings of 11 global airports, including Heathrow. “We expect [global airline] passenger numbers will stay below pre-pandemic levels through 2023,” it said in May, noting airports will likely push expansion plans back due to a lack of cash.

Several airlines including Ryanair, Air France-KLM, British Airways and Easyjet have also reportedly been financially hit in recent months by their practice of fuel hedging — agreeing six or more months in advance to purchase a certain amount of oil at a fixed price. Future contracts, however, will reflect the lower oil price, which could allow airlines to lower their ticket prices further.

Gilles Dufrasne, a Policy Officer for NGO Carbon Market Watch, says there is a real debate about whether “the industry is going to be economically sustainable” regardless of the bailouts: “I think there are serious questions around some of the companies that were clearly in trouble before the COVID-19 outbreak started now getting bailouts,” he says, pointing to the pre-crisis financial troubles of Boeing and Alitalia.

Workers versus shareholders

The aviation industry has been leaning heavily on its contribution to employment to justify the need for bailouts. But in the wider COVID-recovery context, it is debatable whether airlines should be prioritised for bailouts over lower carbon sectors that are also major employers.

Like many industries, the aviation sector is facing huge job losses. Some airlines are already downsizing to weather the crisis. “We’re looking to make sure we’re right-sized, and we’ll continue to do so,” said Doug Parker, chief executive of American Airlines in May. In July, the airline announced plans to furlough up to 25,000 workers. United Airlines has also said it could furlough up to 36,000 workers, nearly 40 percent of its staff, while in the UK British Airways has been criticised by MPs for plans to fire then rehire staff on lower pay.

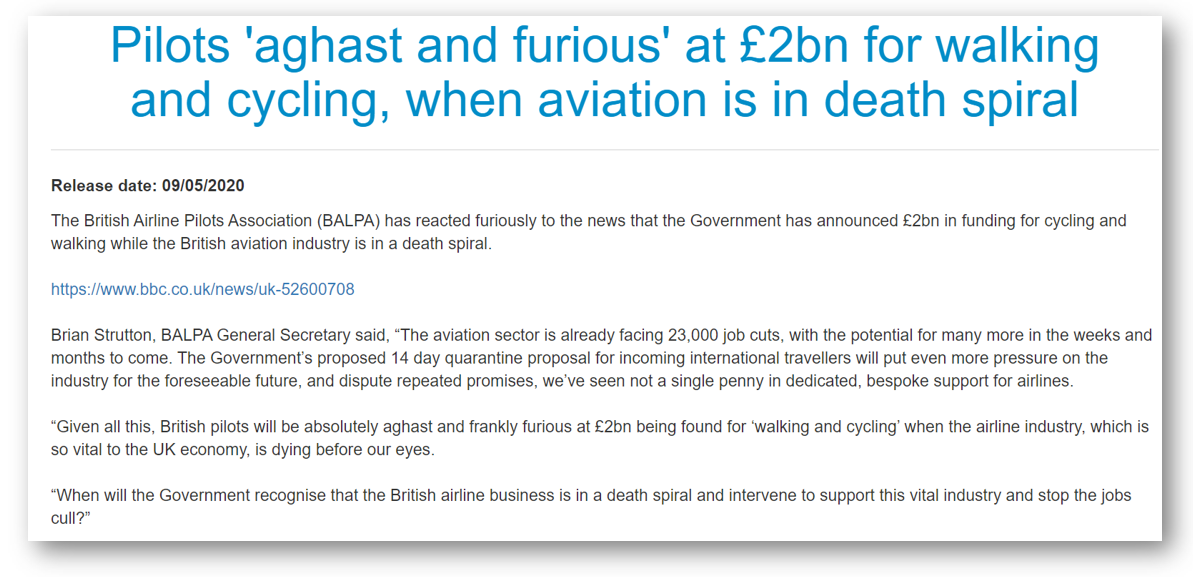

In May, the General Secretary of the British Airline Pilots Association (BALPA) reacted with fury at the news that £2 billion was being given to walking and cycling when “we’ve seen not a single penny in dedicated, bespoke support for airlines”.

But Reeves disputes that the sector’s jobs should take precedence. “I’m not sure if that’s really well founded in economic terms that you should spend your money on airlines instead of, for instance, on arts or on the cultural sector,” he says.

Source: BALPA press release

Meanwhile Baroness Bryony Worthington, life peer and lead author of the UK‘s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act, tweeted in March that government bailouts should go first to “companies who pay fuel taxes” while aviation, which doesn’t pay fuel taxes “and serves a tiny percentage of people for non essential travel”, can “get to the back”.

The case for taxpayer-funded bailouts looks particularly weak when the cash seemingly could be collected from shareholders. In April, Easyjet faced a backlash after asking the UK government bailout weeks after paying £171 million in dividends to its shareholders, including £60 million to its billionaire founder Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou. Easyjet later secured a £600 million loan from the Bank of England’s emergency bailout scheme, but is still making around 30 percent of its workforce redundant.

Other airlines are now asking for money despite huge payouts to shareholders in recent years. International Airlines Group (IAG), the parent group of British Airways, paid €1.3 billion in dividends to shareholders in 2019, despite a net debt of €7.6 billion. British Airways has now received a £300 million low-interest loan from the Bank of England, while cutting 12,000 staff. In the US, Democrats have criticised the $50 billion of coronavirus aid set aside for airlines given companies spent years of profits buying back their own stock. The four biggest US carriers are together estimated to have spent about $39 billion over the last five years buying back shares.

Airline costs tend to involve only a relatively small share for employees but high share of ownership, which means bailout money which is not earmarked for workers will not necessarily go to support people in their jobs. Money from the UK’s furlough scheme and half of the $50 billion bailout given to airlines in the US had to be used to directly support workers. But much of the financial support offered via bailouts is not this targeted, including the money already signed off by the UK’s Bank of England’s emergency bailout scheme.

“If an airline goes fully bankrupt, then its stockholders lose a lot and anyone who it owes money to also loses money,” says Rutherford. “So by the same logic if a government steps in, provides an airline with a bunch of aid that keeps it from going bankrupt, then you could view that as a subsidy to its stockholders and its debt holders.”

Read more: Aviation Job Losses Show Government Needs to Support Workers’ Low Carbon Transition — Report

Alongside these concerns, there are also questions about the long term viability of employment in the sector, which was already becoming increasingly scarce due to automation. This trend could be amplified by changing consumer behaviour in response to climate policies or environmental concerns.

Airline profits sank in 2019 to the lowest in four years, while bankruptcies soared. US manufacturer Boeing was in trouble well before the coronavirus pandemic, but was supported by the US Federal Reserve to raise $25 billion in bonds, apparently helped by US government action to keep airlines afloat. Meanwhile, there were already indications that strong passenger growth rates in China, the world’s second largest market, were coming to an end. “The economic damage done by COVID has accelerated these trends,” wrote industry consultants Michael Boyd in May.

The UK airline sector has already seen the ratio of jobs to passengers fall substantially over the past 20 years due to rising automation and service cutbacks. Now, over 70,000 jobs in the UK’s aviation sector and its supply chain are at risk in the next few months due to COVID-19, with many of these job losses likely permanent, according to one report. In response, climate campaigners have urged for workers to be prioritised when governments are considering bailouts — both by earmarking bailout money for workers wages and considering the longer term of transitioning aviation workers to cleaner sectors.

From pressure to change to become responsible corporate citizens, to fundamental problems with the sector’s business model, and changing consumer behaviour, airlines are facing multiple challenges to their business-as-usual approach. As ICCT’s Rutherford notes, “it’s not just COVID” driving these changes:

“The global economy was slowing down. And then you had the flying shame movement that was starting to dig into demand as well. So it’s sort of a triple whammy for them. It’s definitely a severe time.”

Image credit: © Sam Whitham/DeSmog. Updated 24/07/20: Paul Peeters’ name and affiliation was corrected.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts