Community leaders long at odds with the powerful petrochemical industry in Louisiana took note when their Congressional representative, Cedric Richmond, announced November 12 that he was taking a new job in the Biden White House. In his announcement, Richmond, a Democratic representative in Louisiana for most of the heavily industrialized region stretching from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, made no mention of his constituents’ ongoing battle for environmental justice.

Richmond has taken hundreds of thousands of dollars in fossil fuel campaign contributions during his career. Despite this history, some fenceline communities in Louisiana are looking forward to the potential of what Joe Biden’s ascension to the White House with Richmond by his side could mean for their majority-Black neighborhoods which are impacted daily by air pollution from an expanding petrochemical industry.

On his campaign website, Biden has called for environmental justice and “rooting out the systemic racism in our laws, policies, institutions, and hearts,” linking this cause to the pandemic, which continues to disproportionately impact people of color.

“Any sound energy and environmental policy must … recognize that communities of color and low-income communities have faced disproportionate harm from climate change and environmental contaminants for decades,” reads Biden’s website. “It must also hold corporate polluters responsible for rampant pollution … [and] means officials setting policy must be accountable to the people and communities they serve, not to polluters and corporations.”

Richmond will become a senior adviser to the President as the director of the White House Office of Public Engagement, giving up his seat in Louisiana’s Second Congressional District that he has held since 2011 — a district which includes seven of the nation’s 10 most polluted census tracts.

Richmond’s Record in Cancer Alley

Robert Taylor and Sharon Lavigne are both Richmond’s constituents. They live in two of the problematic census tracts in an area known as “Cancer Alley” — an 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans that’s lined with dozens of petrochemical plants and oil refineries.

Lavigne is the founder of RISE St. James, and Taylor is the executive director of the Concerned Citizens of St. John the Baptist Parish, two community groups that are fighting for clean air. These two groups, along with state and national environmental advocates, have been fighting for years to stop the expansion of the petrochemical industry in Black communities in Louisiana, and pushing for meaningful action against facilities that exceed safe levels of air pollutants.

“Electing a president who saw fit to mention environmental justice on a national stage during a debate is a step in the right direction,” Taylor said.

Though Biden’s transition team is saying the things they want to hear, Taylor’s and Lavigne’s enthusiasm is measured. Both are taking a “wait-and-see” approach and noting who is joining Biden’s team before considering the president-elect a true ally.

Rep. Cedric Richmond speaking during a visit to the Youth Empowerment Project in New Orleans, Louisiana, on July 23, 2019.

Biden’s choice to appoint Richmond in a role that makes him a liaison between Cancer Alley community leaders and the White House leaves them skeptical because the congressman never accepted any of the invitations to their community meetings, nor spoke publicly about the environmental racism plaguing their communities over the years.

Richmond has a controversial record. He has broken with the Democratic Party on major climate and environmental votes, as Politico reported. And the congressman has voted with Republicans to allow for an increase in fossil fuel exports and in favor of pipeline development. Richmond has also come out against Democratic legislation setting pollution limits on the fracking industry and for GOP legislation to limit the Obama administration’s authority to more stringently regulate it.

In December 2019, the Guardian reported that Rep. Richmond was one of the top recipients of donations from the oil, gas, and chemicals industries in the Democratic House caucus. Richmond has taken over $400,000 in campaign donations from the oil and gas industry and chemical manufacturers in his almost a decade in office. Including the 2020 campaign cycle, that number has risen to nearly a half million dollars, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics.

The Guardian analyzed Richmond’s news releases and found that he had not mentioned air pollution in his district at any point during his tenure and that his congressional records suggested he has not spoken about the issue in Congress.

New Troubles for Formosa Plastics

One major reason for Lavigne’s skepticism about Richmond is his silence on Formosa Plastics’ sprawling $9.4 billion manufacturing complex proposed for St. James Parish. Lavigne and other environmental advocates see that plastics project as the largest threat to their community.

Lavigne’s repeated requests for Richmond to help stop the project over the years have gone unanswered. Nevertheless, her group and numerous allies have been battling Formosa in court — and those cases have created new stumbling blocks, even after the project already has received its permits. This month, federal and state regulators are reexamining key permits previously issued for this plastics complex, based in part on concerns of environmental racism raised by lawsuits.

On November 18, state judge Trudy White sent critical air permits for Formosa’s project back to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ), directing the agency to take a closer look at how the plastics facility’s emissions will impact the predominantly Black community living nearby. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) already has cited this region for its elevated levels of air pollution.

White’s judgment followed the Army Corps of Engineers’ announcement on November 4 that the agency will reevaluate its federal wetlands permit for Formosa’s project.

In a strong rebuke to LDEQ, according to a partial transcript of the ruling done by nonprofit law firm Earthjustice, Judge White apparently told the agency: “Environmental racism exists and operates through the state’s institutions —through personnel, policies, practices, structures, and history. Intentional or unintentional. The institution must not be righteous and pay lip service to an analysis.”

She went on to say, “LDEQ did not balance pollution health risks with reasonable certainty. It made conclusions without an [environmental justice] analysis.” The agency must now perform a deeper analysis of how building the giant plastics manufacturing complex would affect nearby majority-Black neighborhoods.

Janile Parks, spokesperson for FG LA LLC, a member of Formosa Plastics Group, expressed confidence that the Army Corps’ reevaluation would lead to a reinstatement of Formosa’s wetlands permit. FG LA also said in a statement about Judge White’s ruling on the LDEQ permit that the plastics company intends to explore all legal options.

In response to concerns that the chemical complex is being built less than two miles from Lavigne’s home, Parks told DeSmog via email, “FG placed a high value on the remoteness or distance from nearest residents in order to avoid impacts to residents of established communities.”

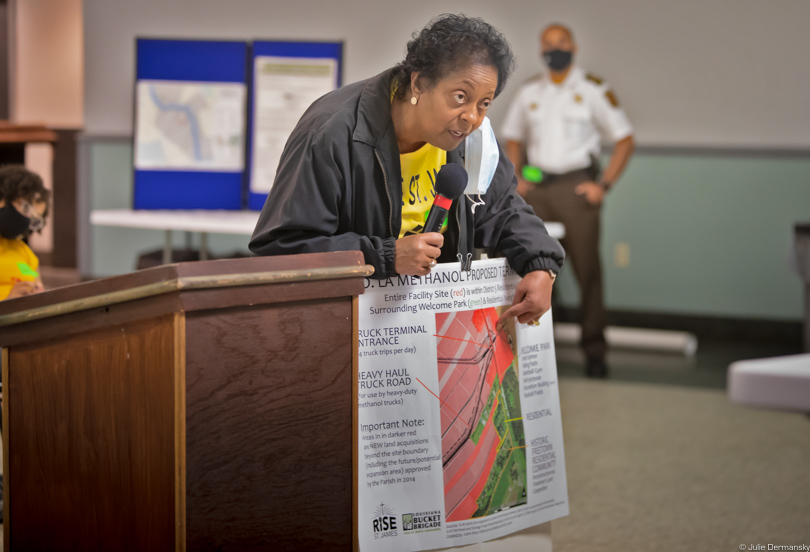

Sharon Lavigne speaking against a permit modification sought by So LA Methanol, another plant poised to be built in St. James, at an LDEQ permit hearing on November 19.

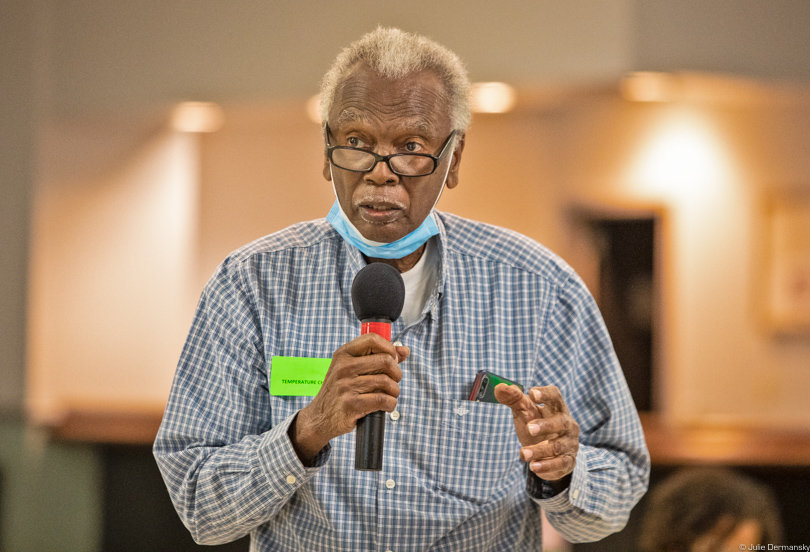

Robert Taylor joining the chorus of St. James community members speaking out against So LA Methanol’s plant to build a new chemical plant in St. James.

Hope for Environmental Justice

With major construction paused on the Formosa complex, Lavigne and Taylor are feeling encouraged. Recent victories, even if temporary, coupled with Biden’s win, give the Cancer Alley community leaders some hope.

Richmond started to address his constituents’ concerns about environmental racism a month after the Guardian exposed his lack of action for Cancer Alley communities. He sent a letter in January 2020 to state and federal regulators voicing his concerns about a toxic facility owned by Japanese chemical company Denka (though it is still linked to its former owner DuPont). In it, Richmond called for a public meeting with the surrounding community about its concerns over changes to air monitoring around the chemical plant. In 2014, the EPA determined that residents in the census tract nearest the plant face the highest risk in the country of developing cancer from air pollution.

Though that meeting has yet to be scheduled, Taylor is hopeful that Cancer Alley groups like his will have their former representative’s ear in his new White House role.

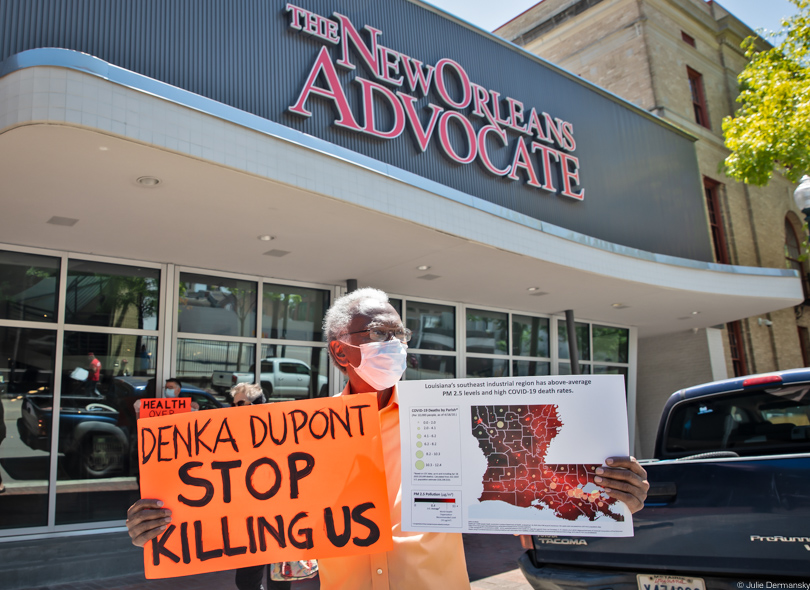

Robert Taylor protesting in front of The New Orleans Advocate’s office on April 24, while Rep. Richmond was inside during a live-streamed town hall event.

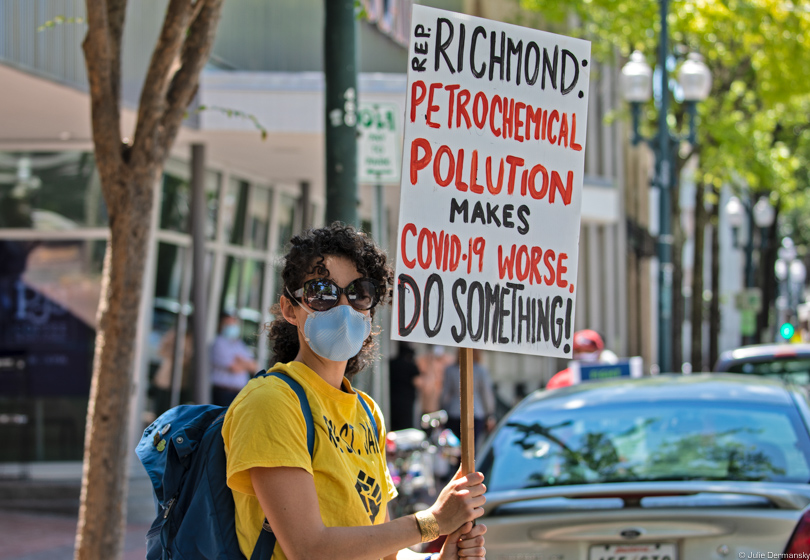

Activist supporting the grassroots group, Coalition Against Death Alley, at a protest applying pressure on Rep. Richmond in New Orleans on April 24.

This spring, Taylor and members of the Coalition Against Death Alley, a grassroots group advocating for environmental justice in Cancer Alley, protested in front of the newspaper The New Orleans Advocate’s office on April 24 when Richmond was there to do a live-streamed town hall event.

Confronted by the protesters when he left the building, Richmond spoke to them for a few minutes until the exchange turned contentious. He later reached out to Taylor directly by phone. Taylor, unfortunately, missed the call and hasn’t pressed Richmond to set up an in-person meeting due to concerns about the pandemic.

“Richmond made some promises to us and I’m hoping that he is in a better position to make good on them,” Taylor said. “He has fought for criminal justice and health care reform, which we also need.”

Rep. Richmond speaking to Cancer Alley community members who protested in front of The New Orleans Advocate on April 24.

Like Taylor, Lavigne is hopeful that with Richmond’s new position in the Biden administration, he won’t forget where he comes from, and that he will help turn into reality Biden’s environmental justice plan. This plan includes several initiatives from Cancer Alley activists’ wish lists, such as expanded pollution monitoring and real-time community notifications for pollutant releases.

But Lavigne expressed frustration that Rep. Richmond has not weighed in on Formosa’s massive plastics project despite construction at its St. James site starting earlier this year. “He hasn’t tried to help us so far. So, why would I think he is going to help us now?” she said.

Lavigne, however, did acknowledge that Richmond hasn’t been completely unresponsive. He called her earlier this year after she reached out to his aide to express her concern over Bill 197, which would have made it a more serious crime to trespass on Louisiana’s so-called “critical infrastructure,” including the state’s system of flood-control levees, fossil fuel pipelines, and sprawling network of petrochemical plants and refineries. (Though the bill passed the state legislature this June, Gov. John Bel Edwards vetoed it.)

DeSmog reached out to Rep. Richmond’s communications director, Jalina Porter, on November 18, inquiring about Richmond’s past efforts to work on behalf of Cancer Alley communities. DeSmog asked why fenceline community members shouldn’t worry about having Richmond’s ear once he is in the White House, despite his perceived conflicts of interest due to the sizable donations he’s received from the fossil fuel and chemicals industries.

Porter said she flagged the request to the Biden transition team, which did not respond in time for publication.

Long Road Ahead

Richmond’s slow but increasing engagement over Cancer Alley concerns have community leaders feeling cautiously optimistic about his appointment, given their former representative’s familiarity with their battles. More troubling to Lavigne and Tayler is Biden’s transition team appointment of Michael McCabe to its EPA review team, which has an influential role in shaping the future operations of the agency. Though his current role is voluntary, McCabe’s ties to the petrochemical giant DuPont raise red flags for Taylor.

The Intercept reported that McCabe went from his position as deputy administrator of the EPA at the end of the Clinton administration to a consulting job with DuPont, where he used his relationships with his former federal coworkers to help the chemical giant avoid EPA regulation of a toxic chemical used to produce Teflon. According to the Intercept, the Biden transition team said McCabe “has also committed to not taking a position within the Biden administration,” which means his direct influence will likely end after the transition.

Taylor’s community shares a fence line with a DuPont chemical plant that was purchased by Denka in 2015. The plant produces the synthetic rubber Neoprene and emits numerous toxic chemicals, including chloroprene, an air pollutant the EPA reclassified in 2010 as a likely human carcinogen

Since buying the plant, Denka has made considerable improvements to cut its chloroprene emissions but has not lowered them to the level that the EPA suggested would be safe for the community.

Biden and Richmond both got Taylor’s and Lavigne’s votes. But neither community leader expects environmental justice to come easily just because President Donald Trump will be leaving the White House.

Over the years, both political parties have failed fenceline communities in Louisiana, which is why the two leaders and their scrappy groups plan to keep fighting for cleaner air.

They hope that Biden’s victory and the pending reviews of the Formosa Plastics project will help usher in a new era of environmental justice for their corner of Louisiana.

Main image: Former Vice President Joe Biden with Rep. Cedric Richmond visiting the Youth Empowerment Project in New Orleans, Louisiana, on July 23, 2019. Credit: All photos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts