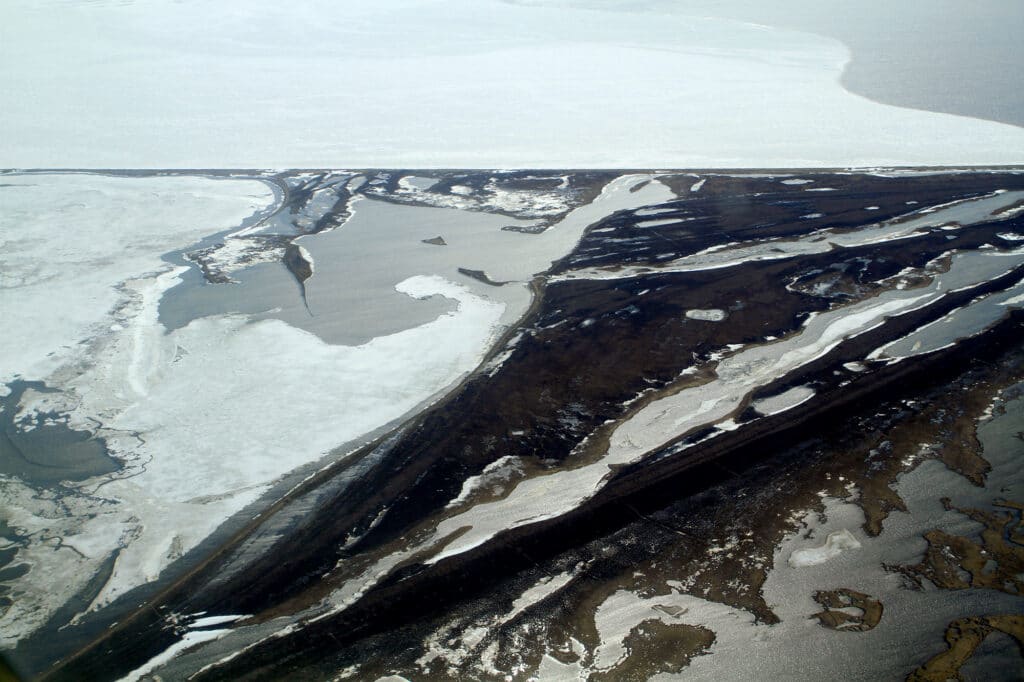

Each storm season brings increased stress and fear for the people of Kivalina, a tiny Native village of some 400 Inupiaq people that sits on a small barrier island on the shore of the Chukchi Sea in Alaska. For decades, there was no reliable way of evacuating people in the event of a severe storm; the only way on or off the island was by small plane or boat, neither of which are available or safe during high winds, storm surges, and inundation. A bridge to the mainland was only recently completed. Meanwhile, the island is rapidly eroding out from under the village.

When fierce storms appear on the horizon, the children get especially anxious and the elderly worry, which has impacts on their health. Increasingly hotter global temperatures mean the sea ice, which would have formed a barrier to protect the island from storms, forms much later in the storm season and melts much sooner. Without that protective sea ice, the island’s residents know that the community’s burial site, and the remains of 400 of their ancestors, will one day wash away. Meanwhile, the permafrost that Kivalina sits on and that forms the banks of the river that sustains their community is melting and eroding into the water, threatening their drinking water treatment system and creating potential health problems. The island’s shrinking footprint prevents the village from building sufficient housing, causing dwellings threatened by an encroaching sea to become overcrowded.

In a small but noble effort to protect their homes, the children of Kivalina gather stones and carry them to a spot on the beach between the sea and their village. One beside the other, they plant them upright in the sand, until a tiny wall faces the sea.

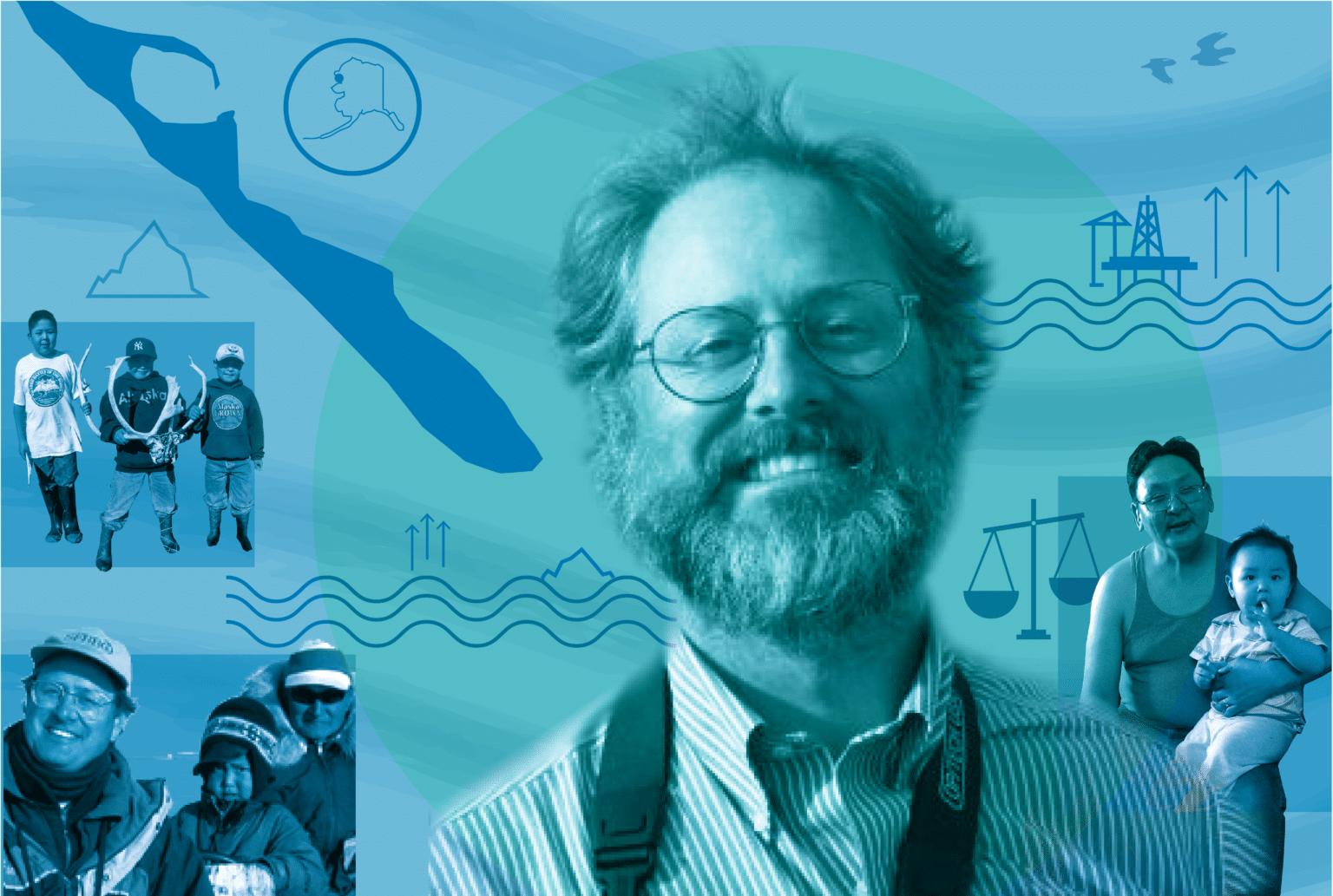

At the turn of the 20th century, the Indigenous people in the surrounding area were forced to settle on this island by the U.S. government under threat of imprisonment. As early as 1910, residents of Kivalina, a federally recognized tribe, have wished to move from the site for fear of erosion, seeking help from state and federal agencies to relocate their village with little to no responsive action. After decades of fighting for their sovereignty and survival, the community found a new friend. In the early 2000s, the challenges faced by the community came to the attention of an environmental justice lawyer named Luke Cole. Working closely with the community, Cole represented the residents in lawsuits fighting against major mining and fossil fuel companies, including the groundbreaking case Kivalina v. Exxon. The implications and ingenuity of the suit gave the people of Kivalina an international media platform to raise awareness of their ongoing fight to survive the perils of climate change.

And although the tribe was fighting for its sovereignty long before Cole was born, as friendships flourished between Cole and the people of Kivalina, these relationships empowered him and the community, and ultimately helped shape the future of climate litigation and climate justice movements around the world.

Cole’s journey was tragically cut short in 2009 before he could see the full impact of his life’s work unfold. And while many in Kivalina continue to struggle with the loss, the legacy of their work together lives on in the now-commonplace notion that climate change isn’t just an environmental issue — it’s a human rights issue.

Fighting for Justice

Bespectacled, tall, and barrel-chested, with blonde hair and a beard punctuated by gray, Cole stood confidently before a classroom of conference attendees at a University of Oregon environmental law symposium in 2008, less than a year before his death. In a video recording of the event, Cole asserted that where fossil fuel energy is extracted, refined, transported, used to generate power, and disposed of in toxic waste dumps, it “is highly correlated to low income communities and communities of color.”

“Almost all aspects of our energy economy thus have environmental justice implications. That impact carries over directly into the climate change context,” he concluded.

Cole’s work was dedicated to representing communities of color around the country, including Kettleman City, California, and Camden, New Jersey. He developed a form of environmental justice law focused on community empowerment and mobilization. To support this work, he started the Center on Race, Poverty, and the Environment (CRPE) in 1989 with the help of his mentor Ralph Abascal, a preeminent poverty lawyer who began his career working with Chicano Rights leaders César Chávez and Dolores Huerta. Abascal gave Cole a desk and a phone, and Cole got to work.

Cole argued that the law was not the ultimate weapon, but only one, and that the overarching goal is political empowerment toward systemic change.

According to Cole’s friend, founding chair of the CRPE Board of Directors, and retired UC Berkeley law professor, Angela Harris, Cole was mindful of the vision of environmental justice forefather Dr. Robert Bullard, who she said pioneered the idea, “that protection of the environment and the subordination of poor people and people of color were not competing goals, but rather tied up with one another.” She said in this way Cole looked at how poverty law could be brought together with environmental law. For example, she says Cole understood well that poverty is a feature of how we accumulate and extract in our economic system.

Harris said that to address this systemic problem, Cole argued that the law was not the ultimate weapon, but only one, and that the overarching goal is political empowerment toward systemic change. This philosophy led Cole to structure CRPE so that community organizers were in the lead and lawyers would be accountable to the organizers. This structuring would lead to the sorts of structural transformations Cole and others were working to accomplish, according to Harris.

To this day, a book published in 2001 and co-written by Cole with Georgetown law professor Sheila Foster titled, From the Ground Up, is considered a treatise for the type of environmental justice work he practiced and taught. At the time of his death, Cole was working with Foster on a second edition of the book, which never came to be but would have included chapters on Kivalina and Hurricane Katrina and highlighted the systemic inequities faced by communities of color in the context of climate change and how environmental justice movements might mobilize to address them.

Echoing those unrealized book chapters, last year Kivalina joined forces with several Louisiana tribes that were impacted by Hurricane Katrina. Along with the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians of Louisiana, Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe, Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, and the Atakapa-Ishak Chawasha Tribe of the Grand Bayou Indian Village of Louisiana, Kivalina brought a human rights complaint to the United Nations. They allege the U.S. government has failed to protect their human rights by failing to “engage, consult, acknowledge and promote the self-determination” of Kivalina and the Louisiana tribes. “By failing to act, the U.S. government has placed these Tribes at existential risk,” the complaint claims.

Early Influences

A white man raised with financial means in America, Cole was able to attend private preparatory school, graduate from Stanford University, and then go on to Harvard Law School. From a young age, Cole was not only argumentative, but also aware of the global realities of racism and privilege. According to his mother, while the family was living in Nigeria, a three-year-old Cole wandered a marketplace and saw a Black child who held a tray on his head with pens and toilet paper atop it, which he was selling. The two boys were around the same age and height, and when Cole’s eyes met those of the other child, his mother says he realized his privilege in a way he hadn’t before — that the trajectory of the other boy’s life was much different than his own. Cole’s family believes this formed the basis for his later environmental justice work.

As he came of age, Cole was shaped by his teachers in ways that directly contributed to his work with the people of Kivalina. While at Stanford University, political science professor John Manley, who used the Marxist critique of power in the U.S. and wrote about social justice, had a significant influence on him.

Cole was innovative and persistent, remembers Ralph Nader. Following his graduation from Stanford in 1984, Cole worked for Nader for three years, writing a monthly consumer advisory. “He obviously learned the lessons of [American political activist] Eugene Debbs who said, ‘If you’re not willing to lose, lose, and lose until you win, you’re not going to win.’ He would break new ground, and he might lose, but he keeps trying again,” Nader said. “It gave him energy to go after the big guys.”

In 1987, while in law school at Harvard, Cole traveled to South Africa on a Harvard Human Rights Fellowship and volunteered for the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at Wits University. Observing apartheid firsthand, he saw a government bent on maintaining racial segregation laws that had economic implications and the lengths to which it would go in order to maintain this systemic injustice. Cole watched anti-apartheid lawyers working in interdisciplinary ways to develop innovative approaches. Kevin Reed, a law school colleague of Cole’s who accompanied him to South Africa, said he sees a direct line between their work in South Africa and how Cole developed as an environmental justice lawyer; as someone with “profound respect for the power of the people.”

Reed said that Harvard professor Gary Bellow had a big influence on Cole during his law school years. Bellow was a public interest and poverty law specialist and founded a legal clinic in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston. Cole later quoted Bellow in an article as saying, “[t]he worst thing a lawyer can do — from my perspective — is to take an issue that could be won by political organization and win it in the courts.”

Rhode Island School of Design environmental studies professor Lauren Richter, who worked for Cole at his nonprofit, says she has often heard people remark on how he used his privilege to “intervene in injustice.” She cited an infamous 1971 memo written by soon-to-be Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell that claimed the “free enterprise system” was under attack by charismatic “respectable liberals” like Nader. “There appears to be a particular kind of outrage and anger at privileged, Ivy League educated white men who dedicate their lives to addressing injustice,” Richter said. “It’s interesting to think about why that is, and why it remains so uncommon.”

A Personal Relationship

In 2001, Cole met Colleen Swan, a citizen of Kivalina, during an environmental workshop in Kotzebue, Alaska, following a presentation he gave. At the time, Swan was raising issues about the Red Dog Mine, which lies upstream of Kivalina and drains into the Wulik River, “because it was obvious to our people, especially the elders, that something was wrong with our drinking water,” she said. The Wulik River serves as Kivalina’s drinking water and subsistence food source for trout, and Swan had been reviewing discharge reports associated with the mine that revealed contaminants above allowable limits, she said. During a break, Cole asked Swan if Kivalina needed any help dealing with the problem. “I couldn’t believe it because nobody wanted to deal with it in the State of Alaska,” she said of Cole. This marked the beginning of a connection that would later spur the community’s lawsuit against the mining company and cement a relationship that continued until Cole’s death.

Swan said Cole came to Kivalina to take on the Red Dog Mine, and if he hadn’t, there is no way they could have fought them because they didn’t have the financial means. “His passion for environmental justice comes from love for people — he treated you like you mattered,” she said. “No one else listened to our concerns. Not any Alaskan lawyers, not regional elected leaders, not our own state or federal government representatives.”

“He loved my mom’s sourdough pancakes,” said Kivalina citizen Enoch Adams, Jr., adding that Cole shared the community’s traditional foods alongside him and his family, and stayed in their home during his early visits to the remote village. Cole’s relationship with the people of Kivalina became increasingly personal. “The attorney-client relationship was there,” Adams, Jr. said, “but that became secondary.” When his son was born, Adams, Jr. named him after Cole.

“Luke had high moral and ethical standards and he fit right into our community,” Swan said. “Those standards are the foundation on which our system of self-governance rests.”

Cole built his career as an environmental justice lawyer who empowered communities cast aside by America. The people of Kivalina are a prime example of this.

“He was all about justice,” Swan said of Cole. “There were times when he got so angry that people like us were being treated like we were being treated. I mean it angered him.”

Driven by this injustice, Cole took unprecedented action, with the help of others, to help correct it.

Early Kivalina Lawsuit

That chance encounter with Swan in Kotzebue led to Cole representing Kivalina in a lawsuit in 2002 against one of the world’s largest zinc mines, Teck Cominco’s Red Dog Mine, alleging that the Canadian mining giant was polluting the Wulik River.

In 2003, intruders broke into the office of CRPE, the small nonprofit Cole had founded. Two mini-computer towers, back-up computer disks, and a briefcase were stolen, containing internal information regarding the organization’s work from the previous year. “This was an attempt to disable us, intimidate us and hinder our work,” Cole was quoted as saying in a news report at the time. The burglars were never caught. Around the same time, Cole noticed someone going through the papers in his recycling bin outside his home. Again, no one was ever caught. There is no indication of Teck Cominco’s involvement.

In 2006, a federal judge found the mine had violated the Clean Water Act over 600 times. The case was settled two years later, with the company agreeing to build a 55-mile pipeline to carry mine wastewater to the sea at the estimated cost of $120 million. But in 2014, the company opted out of building the pipeline because they said it wasn’t feasible given permafrost conditions. Instead, Teck Cominco paid an $8 million civil penalty.

Children use water provided by Teck Cominco in May 2014 after the company declined to build Kivalina a pipeline to carry the Red Dog Mine’s wastewater to sea. Credit: Suzanne Tennant A child plays in meltwater in May 2014. The permafrost under Kivalina is thawing. Credit: Suzanne Tennant

Landmark Climate Change Lawsuit

In 2008, Cole, along with a team of lawyers, represented Kivalina in a now famous climate lawsuit against some of the largest fossil fuel corporations in the world, including ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, and Shell. The suit, Kivalina v. Exxon, was filed in February 2008 in U.S. District Court. Cole was the lead counsel listed on the complaint, along with Brent Newell, CRPE’s legal director at the time, and Heather Kendall-Miller of the Native American Rights Fund. A team of lawyers from other firms were also listed as counsel, including Matt Pawa, a leading climate change litigator who said the suit “was the first major court case seeking money damages against polluters for the climate crisis.”

The lawsuit alleged that damages were owed from the fossil fuel and power companies for causing climate change by emitting greenhouse gases, which in turn warmed the Arctic and prevented sea ice, which is commonly present in the fall, winter, and spring, from forming around the village’s island. “The sea ice — particularly landfast sea ice — acts as a protective barrier to the coastal storms that batter the coast of the Chukchi Sea,” according to the lawsuit. Citing global warming as the cause, the suit alleged that, “sea ice forms later in the year, attaches to the coast later, breaks up earlier, and is less extensive and thinner, thus subjecting Kivalina to coastal storm waves and surges. These storms and waves are destroying the land upon which Kivalina is located.”

The suit alleged that impacts of fossil fuel-driven climate change have damaged Kivalina to such a degree that it is becoming uninhabitable and the entire community must be relocated lest it “cease to exist.” The plaintiffs sought to recover $95 to $400 million from oil, gas, and power companies to relocate the village of Kivalina to a site further inland, safe from the deadly flooding caused by the storms, the likes of which the village experienced with increasing frequency beginning in 2004.

Pawa said the lawsuit caused people to think of climate change as a liability issue, and raised an important question: “If a fossil fuel company or a greenhouse gas emitter is profiting from the destruction of the planet, shouldn’t they be forced to internalize those costs?” It’s a question many are asking today, he said, but not so many were in 2008.

That same year, despite the global financial collapse, some of the defendants were raking in billions in profits. Exxon netted $45.2 billion in 2008, while Chevron netted $23.9 billion.

The lawsuit was also the first to allege that some of the corporations committed civil conspiracy in misleading the public about the impacts of climate change and the fact that it’s primarily caused by humans burning fossil fuels.

“There has been a long campaign by power, coal, and oil companies to mislead the public about the science of global warming,” the lawsuit stated, specifically naming ExxonMobil, AEP, BP America Inc., Chevron Corporation, ConocoPhillips Company, Duke Energy, Peabody, and Southern as participants in this alleged campaign. The lawsuit described these actions as a “nefarious campaign of deception and denial intended to manufacture a false sense of public uncertainty regarding the science of global warming.”

On behalf of Kivalina, Cole and others claimed the purpose of this campaign was to enable these companies to continue contributing to global warming by convincing the public that global warming is not caused by people, “when in fact it is,” the complaint said.

Luke Cole’s colleague Brent Newell, left, and Enoch Adams, Jr., center, and his family in May 2014. Credit: Suzanne Tennant Kivalina’s children play in puddles from the Arctic village’s melting permafrost. Credit: Suzanne Tennant

A decade later, as a slew of climate lawsuits calling out industry disinformation started flooding the courts, Harvard history of science professor Naomi Oreskes testified before Congress in October 2019 that the fossil fuel industry “systematically misled the American people, and contributed to delay in acting on the issue” of climate change. Research by Oreskes and her Harvard colleague Geoffrey Supran concluded that ExxonMobil misled the general public about climate change.

According to Katrina Fischer Kuh, environmental law professor at Pace University, there have been no new claims that have similarly alleged civil conspiracy, “but the facts underlying the civil conspiracy claim, relating to the fossil fuel disinformation efforts on climate change, have been incorporated into the second generation common law climate change lawsuits, including in some cases as part of their failure to warn claims related to product liability,” Kuh said in an email.

Kivalina’s lawsuit was compared by some prominent observers at the time to early tobacco industry litigation cases. In a New York Times article, Michael Gerrard, Columbia University law professor and director of Columbia’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, was quoted as saying that, similar to the Kivalina suit, the early attempts to sue big tobacco appeared weak. “They lost the first cases; they kept on trying new theories, and eventually won big,” Gerrard told The Times.

A Tragic Accident

But, at the age of 46, just over a year after filing Kivalina v. Exxon, Cole was unexpectedly killed on June 6, 2009, while on sabbatical in Uganda.

Cole lived by the credo “work hard, play hard,” and was taking four months off to travel after years of dedicated work. An avid birder, he first went to South America to visit friends. Then, he flew to the tip of that continent, boarded a ship, which carried him and fellow birders across the Atlantic Ocean to South Africa. Soon after, he traveled north to Uganda, to meet with his brother, Tom. Cole’s wife, Nancy Shelby, then joined him for the remainder of his trip.

A young Luke Cole on the beach. Credit: Nancy Shelby Luke Cole with king penguins on a trip to South Georgia, an island in the south Atlantic Ocean. Credit: Debra Shearwater

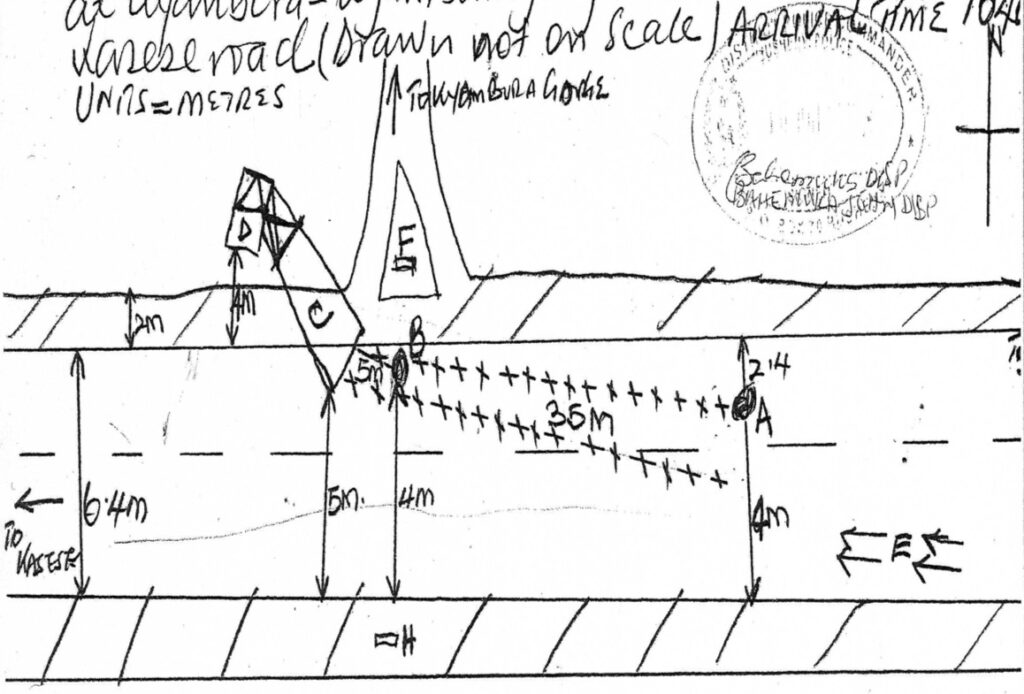

On a bright, clear morning, Cole and his wife drove down a well-paved road in a rented Land Cruiser from Jacana Safari Lodge in Queen Elizabeth National Park to Kyambura Gorge, where they hoped to see gorillas. Driving on the left side of the road, as is standard in Uganda, Cole saw a small sign that pointed them toward the road to Kyambura Gorge. What he didn’t see, however, was a semi-truck speeding behind them as he turned right.

As Cole was turning across the road, the semi-truck hit them as their vehicle was at a 45-degree angle, driving the Land Cruiser into a ditch beyond the turn off.

A drawing in the police report shows the skid marks made by the semi-truck track diagonally across the road from the left to the right lane.

Two wildlife guides who were walking by at the time flagged down a taxi, which drove Cole and his wife to the hospital. Cole died from his wounds soon after, and Shelby was flown to Amsterdam where she was treated before returning home to California where she underwent an extensive period of recovery from her injuries.

Cole’s untimely death was mourned by many, including the people of Kivalina, according to Caroline Farrell, who took the helm of Cole’s nonprofit legal center following his death. She said Cole’s relationship with the people of Kivalina was similar to the relationships he had with other clients, many of them communities of color. “He knew their families,” Farrell said. “He knew who they were as people, and he wasn’t just concerned about the one issue that he was helping them with. He was interested in all of it.”

Dismissed But Not Lost

Just three months after Cole’s death, in September 2009, the Northern District court dismissed the Kivalina v. Exxon case.

Brent Newell, Cole’s colleague at CRPE, said the Court held that Congress, by passing the Clean Air Act, which authorized the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate greenhouse gases, displaced Kivalina’s claim for damages under the federal common law of public nuisance. Basically, he said, “the court said because the EPA had the authority to regulate greenhouse gases, Kivalina couldn’t recover damages in federal court for the massive harms these fossil fuel corporations had inflicted on them.”

However, Newell said he respectfully disagrees with the Court in this case because when Congress passed the Clean Air Act, they didn’t provide monetary damages as a remedy for those harmed by air pollution, which he says is important because Kivalina sought monetary damages for relocating their village from the threats of climate change. Even if Kivalina could have brought a claim under the Clean Air Act and won, he said, those penalties would go from the corporations to the federal treasury, leaving the beleaguered Arctic village just as badly off.

Newell said the ruling didn’t affect other plaintiffs from bringing claims under state common law in state court, which he said has been done since. However, Kivalina hasn’t filed a lawsuit under state common law.

The Court also didn’t rule on the conspiracy allegations. Kivalina’s legal team included people who had been part of the notorious years-long tobacco litigation in the 1990s. But Cole’s vision of the path of climate lawsuits was different. “My hope is that the tobacco litigation is not the model that we’re going to be following. My hope is that the Holocaust Reparations cases are going to be the development of the law model we’re going to follow,” he said in a conference talk in 2009, not long before his death.

The legal team continued on without Cole and appealed the dismissal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which in September 2012, affirmed the lower court’s dismissal. They then tried, unsuccessfully, to have the case heard by the Supreme Court.

But the suit was bold, said Pawa, who has been involved with a number of recent climate lawsuits against fossil fuel companies. It helped people think about climate change as caused by “bad corporate actors doing bad corporate things despite their knowledge of the harm.”

Newell adds that the case helped shift the narrative on climate change by generating significant national and international media attention on the struggles of a tiny Arctic village. “It helped people understand that communities like Kivalina were suffering tremendously because of the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions,” he said.

Swan said that despite her community’s legal loss, people like Cole and Pawa “had the tools and the knowledge necessary to turn our hopeless situation into one of hope.”

“The people outside watching this lawsuit can only see that we lost in court on the climate lawsuit,” Swan said. “To me, we won in more ways than can possibly be imagined.”

Cole’s Legacy

Looming over this, though, was Cole’s death. “When Luke was gone, that was the hardest thing I had to face,” Swan said. She took charge for her community, saying she used knowledge of her traditional ways. “I was forced to call on what I know about our people’s history of self-governance,” she said. “That meant learning to recognize those ‘traditions’ as customary laws and their compassionate spirituality and societal customs, the foundation of which are basic human ethical and moral standards that we all share as human beings.” Swan says this knowledge helped her in continuing to fight on behalf of her community.

Following Cole’s death, most people believed it was a tragic accident, but some speculated it may have been intentional. However, Caroline Farrell, Cole’s colleague, doubts this is the case, saying that such a monumental loss may have led some to believe there was a monumental reason for it. She believes Cole’s death might have been the result of a very bad set of circumstances. This conclusion is the consensus of those closest to him.

Harris, the founding board chair of Cole’s legal nonprofit, says that although the movement lost a powerful figure when Cole died, the vision he was working for — “of empowerment for the poor and communities of color, and his desire to stop this system of extraction and accumulation” — is in some ways more powerful than before. “I feel the loss personally for this person that I cared about,” she said. “But I think the work really continues, and that he is present in the work.”

Cole’s bold and innovative work with the people of Kivalina lives on as the community today pursues climate justice through the United Nations.

“Whatever he did was designed to empower us, to give us a voice.”

Collen Swan, Kivalina citizen

In January 2020, Kivalina and the Louisiana Tribes brought their joint complaint to the UN, alleging that the U.S. government has failed to protect them from the impacts of climate change, and have thus violated a number of their human rights: to self-determination, cultural heritage, subsistence and food security, individual and collective rights to safe drinking water, physical and mental health, and an adequate standard of living.

The UN responded to the complaint on September 15, 2020, and will soon be conducting a site visit to investigate the claims.

“The tribe feels that the government failed them in the efforts of relocating the village,” Kivalina tribal administrator Millie Hawley said, “and they’re looking for funding to relocate the village — that risk of losing their lives now — it used to be just losing infrastructure — but now it’s losing lives actually in the event of an ocean storm surge.”

“Once you’ve made the connections between environmental harm and human rights, then climate change as this massive global environmental harm would adversely affect human rights in all kinds of ways,” said John Knox, Wake Forest University law professor and former UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment. He said Cole’s efforts with Kivalina can be thought of as part of a larger movement to take a rights-based approach to environmental issues, and climate change is primary among them.

Knox says some of the most successful climate lawsuits globally are grounded in human rights arguments. And according to Knox, the UN Human Rights Council is currently considering whether or not to appoint a Special Rapporteur on human rights and climate change.

The U.S. Ambassador to the UN didn’t respond to requests for comment regarding the complaint.

Today, Kivalina’s immediate prospects for relocating are dim, but the community continues to fight for the resources to adapt to the changing climate. Between 2009 and 2010, the community began construction of a rock revetment — essentially a sea wall — but funding ran out before it could be finished. Although it has served to protect Kivalina’s people to some degree from storm surges and flooding, this rocky barrier will only last 10 to 15 years, and according to Hawley, the revetment is already sinking into the ocean — by eight feet according to her estimate. In 2019, the Alaska Department of Transportation started building an evacuation bridge and road connecting the beleaguered Arctic island to the mainland. But seven miles inland, at the new road’s end, the village’s new school has only just begun construction, with completion scheduled for August 2022. A large bus barn is scheduled for completion by this fall, which can serve as shelter if the school isn’t complete, according to the school district.

But the disappearance of protective sea ice has hit home for the tribe in other major ways too, according to Hawley. “It’s even hard to talk about because it’s a dying culture,” Hawley said. “We used to harvest our bearded seal and live on our seal oil and meat throughout the winter every year, and we never worried about food, but after two or three years without the barrier, due to lack of ice … it really affected us in that way,” she said.

Meanwhile, the planet continues to warm rapidly and Kivalina is still very much under existential threat — more so with each degree of warming and each passing storm season. Some reports suggest Kivalina may be uninhabitable as early as 2025. Nevertheless, its citizens are still fighting for their future as a sovereign tribal nation, trying to survive climate change with their culture intact by relocating off the island.

Like the people of Kivalina with whom he worked, Cole never gave up. He only did so because he died. Those who knew him well say he was only getting started. His task? Infusing climate change mobilization with the tools of environmental justice law he’d worked so hard to develop. His goal? No less than changing an oppressive system that is destroying the planet. And although his work as an environmental justice lawyer is over, it continues on in those he influenced, knew, worked with, and loved.

“The voice that he gave me will never be silenced because of what he did for us,” Swan said. “I’m not the only one either.”

“Whatever he did was designed to empower us,” Swan said, “to give us a voice. It didn’t stop with a judge’s decision or a government decision. It didn’t end when we didn’t get what we wanted — no matter what it is — no matter what avenue we took. It didn’t stop.”

CORRECTION (4/13/21): The original version of this article stated that the U.S. government forced Indigenous people to settle on the future site of Kivalina around the turn of the 19th century, not the 20th century. That has been corrected.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts