Despite drops in energy usage during the pandemic, coal power use only declined by four percent in 2020, according to a new report.

While coal used for power generation dropped 20 percent in both the U.S. and the European Union last year, the same is not happening in China.

Boom and Bust: Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline, a new report from Global Energy Monitor, found that “China commissioned 76 percent of the world’s new coal plants in 2020, up from 64 percent in 2019, driving a 12.5 GW (gigawatt) increase in the global coal fleet in 2020.”

Global coal power use, however, must drop by 14 percent per year to achieve the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F), according to the 2021 Global Electricity Review by think tank Ember.

Both the Global Energy Monitor report and Ember’s analysis highlight the fact that when it comes to reducing emissions, coal power is not declining fast enough and renewable power is not growing fast enough. And replacing coal power with gas power — which is being advocated by the oil and gas industry and many politicians as a climate solution — is not an effective way to reduce emissions.

“Progress is nowhere near fast enough. Despite coal’s record drop during the pandemic, it still fell short of what is needed,” Dave Jones, global program lead for Ember said in a statement. “Coal power needs to collapse by 80 percent by 2030 to avoid dangerous levels of warming above 1.5 degrees.”

While headlines tout the death of coal, the reality is that coal remains the world’s single largest power source, generating over a third of global electricity in 2020.

China’s Coal Expansion

Part of the reason behind China’s coal expansion is it’s growing demand for power. China’s electricity consumption was 33 percent higher in 2020 than in 2015. For comparison, U.S. electricity consumption was 2.5 percent lower in 2020 than 2015.

While China may be rapidly building out renewable energy for power generation, and has made commitments for emissions reductions in the future, the country’s power demand is outpacing its rate of renewable power expansion. And in 2020, that resulted in a commitment to build a lot more coal.

"A steep increase in coal plant development in China offset a retreat from coal in the rest of the world in 2020, resulting in the first increase in global coal capacity development since 2015"

— Ketan Joshi (@KetanJ0) April 6, 2021

China really hold the master key on this one….https://t.co/dBYwHDtazU pic.twitter.com/ttSPZ5nAVF

China now produces more than half the world’s coal-fired electric power generation and is the world’s biggest carbon emitter. China’s continued commitment to coal will likely risk any plans to limit global warming.

Global Energy Monitor, however, did report progress in some other countries that not long ago were betting heavily on a coal-fired future.

In 2016, DeSmog reported from the annual Energy Information Administration (EIA) conference that countries in Southeast Asia expected a “doubling of electricity demand by 2030, dominated by coal.”

However, climate concerns, trouble financing new coal plants, switching to gas, and cheaper renewables have changed that forecast. As Global Energy Monitor found, in Southeast Asia “coal plant projects struggled to obtain financing.”

This combination of factors led to the cancellation of 62 GW of planned coal power capacity in 2020 in Indonesia, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Vietnam. In Pakistan the new policy is simply no new coal power plants.

“In 2020, we saw country after country make announcements to cut the amount of coal power in their future energy plans,” said Christine Shearer, GEM’s coal program director. “We are very likely seeing the last coal plants in planning throughout most of the world.”

A sign that CO2 emissions are bouncing back after plummeting early in the pandemic — global coal consumption was actually 3.5% higher in the fourth quarter of 2020 than it was in late 2019, @IEA reports: https://t.co/4kkXYlu8FJ pic.twitter.com/l7MX4YnpSF

— brad plumer (@bradplumer) March 24, 2021

Can Coal Replace Natural Gas?

As Ember reported, coal power is losing out to renewable energy around the world but the transition isn’t happening nearly fast enough to address climate change. Part of the problem is that around the world — and especially in the U.S. — coal power has been replaced with gas power (methane/natural gas). Switching to natural gas from coal results in some reduction in carbon emissions but it also contributes greatly to methane emissions, a powerful greenhouse gas that helps drive climate change.

In the U.S., coal switching to gas has led to a small reduction in overall emissions. At the same time methane emissions — driven by the production of natural gas — are at record levels and increasing.

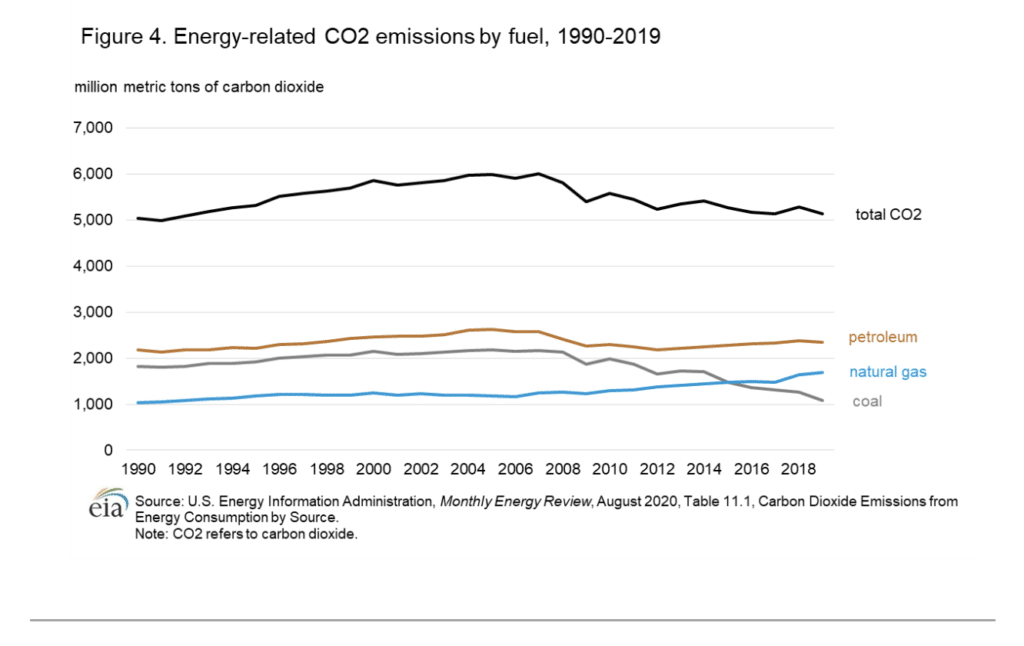

The EIA reported that 121 coal power plants in the U.S. were converted to burn other fuels (mostly natural gas) between 2011 and 2019. While this did result in an overall reduction in carbon dioxide emissions (emissions from coal declined 50 percent from 2007-2019), emissions from natural gas rose over 35 percent in that same time period and methane emissions soared.

Methane is an underappreciated greenhouse gas that packs a powerful punch. Climate pledges should include specific targets to reduce their emissions https://t.co/i7DrQhQyQC

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) April 6, 2021

The oil and gas industry has bet heavily on the future of natural gas to replace dirtier fossil fuels like coal, especially liquefied natural gas (LNG). But even this assumption is being challenged by a growing awareness that LNG is not a clean fuel and that renewables can now produce electricity for lower costs than LNG.

FRACKED GAS IS DIRTY FUEL: The French government blocked a $7 billion LNG deal between Engie and a U.S. gas supplier over concerns that West Texas gas was too dirty. https://t.co/PJfwi27g81

— Dr. Mary Finley-Brook (@geoyapti) October 28, 2020

Despite LNG’s known emissions problems, price volatility, and higher costs than renewable energy, the industry is working hard to build out more LNG infrastructure globally. As the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis reported in March, the U.S. gas industry is trying to convince countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam to switch from coal to LNG instead of renewables.

But with a rapid decline in carbon and methane emissions being necessary to achieve climate goals, experts warn that global coal and natural gas expansion must stop. And unless coal power is replaced by renewable energy sources instead of carbon and methane emitting LNG and natural gas, the path to achieving climate goals appears impossible.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts