Recently the peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature published a ‘pros vs. cons’ piece on the production of unconventional gas from shale. The tête-à-tête, led by Terry Engelder on the pro side and Robert Howarth and Anthony Ingraffea on the con side, weighs the risks and benefits of gas production as it relates to the economy and human and environmental health.

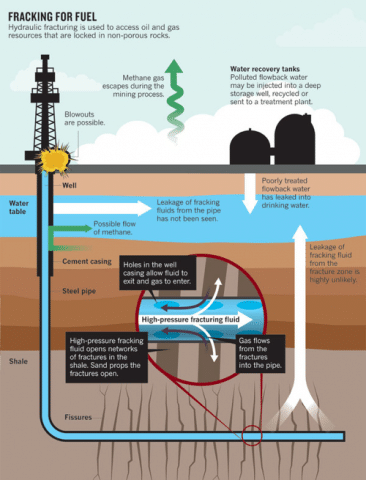

Howarth and Ingraffea, authors of the first peer-reviewed study on lifecycle emissions from unconventional gas production, are solemn in their assessment: “shale gas isn’t clean, and shouldn’t be used as a bridge fuel” to a clean energy future. Their recommendation is based on the risks involved with high-volume slick-water hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, as it exists in its present form.

Although the industry claims to have performed over one million fracking operations since the 1940s, Howarth and Ingraffea counter that the current technology is still relatively new and has only been in operation for a decade. Modern fracking bears little resemblance to its historic counterpart and requires greater amounts of water and chemicals, deeper drilling and higher pressures. All these differences combine to make fracking an unavoidably dangerous process. Howarth and Ingraffea also claim that a switch to unconventional gas will not substantially alleviate global warming in the near future.

Unconventional gas drilling creates problematic waste, not only for the air, but also for land and water. And despite progress made in the regulatory structure surrounding gas drilling, if there is any to celebrate, the process is still inherently dangerous, secretive and exempt from the federal statutes designed to protect human and environmental health.

Overall, when you consider the risks, there is little to prop up unconventional gas as the “clean” fuel of the future. Furthermore, the amount of time and resources devoted to shale gas development stifle the production and commitment to true alternatives.

For all of these reasons, Howarth and Ingraffea call for a moratorium on fracking “to allow for better study of the cumulative risks to water quality, air quality and global climate.”

“Only with such comprehensive knowledge,” they claim, “can appropriate regulatory frameworks be developed,” the Cornell University professors conclude.

But Terry Engelder, a geologist with years of experience working for the gas industry, poses a bold counter claim to Howarth and Ingraffea: “fracking is crucial to global economic stability” and “the economic benefits outweigh the environmental risks.”

Yet Engelder’s assessment rests on a number of assumptions that may prove unsupportable in the long run.

Engelder’s first assumption is that America’s unconventional gas reserves are enough to uphold tremendously high projections of gas production. Such projections underpin the ‘energy security’ of turning to unconventional gas in the wake of oil’s decline. Some say we have about a century’s worth of domestic gas to carry us through to a clean energy future. This will give us energy and economic security as well as a high employment rates and standards of living. (Howarth and Ingraffea, however, point out that emerging data, from the Post Carbon Institute and the U.S. Geological Survey, find these projections to be greatly exaggerated.)

Engelder also presumes that public approval of fracking will support a steady increase in unconventional gas drilling across the country, the increase needed to achieve production projections. Unconventional wells only produce for a short amount of time so a steady increase in production means many new wells must be drilled. But an increase in fracking may have the consequence of increased resistance, which is something already happening across the nation. Opposition to fracking will certainly get in the way of uninhibited drilling, a point Engelder seems to overlook. In fact, Engelder seems to rely upon continued support from people in drilling regions where they are less likely to become anti-drilling activists.

The final assumption that Engelder makes surrounds the broad scope of human and environmental harm. Sounding much like an industry front man, Engelder downplays the risks associated with fracking, suggesting that water contamination has not and will not occur, that methane contamination is basically harmless and naturally occurring, that industry mistakes, like leaks and blowouts “are like all accidents caused by human error – an unpredictable risk with which society lives.” Engelder wants to at once suggest that there are no unmanageable problems associated with fracking and, where there are problems, call them a necessary evil.

In a post-Macondo world, the vague and nonchalant treatment of such serious risks is brazen and inexcusable.

Engelder writes that in the case of fracking “fear levels exceed the evidence.” But this statement holds none of the practical wisdom of Howarth and Ingraffea’s final words: “gas should remain safely in the shale, while society uses energy more efficiently and develops renewable energy sources more aggressively.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts