Climate policy can make for strange bedfellows – perhaps none as strange as the former vice president and Republican senator from Oklahoma, whose views on most issues could not be more divergent. Yet on one issue – related to climate change, no less – they agree: black carbon, or, as it’s more commonly known, “soot,” is a dangerous pollutant that deserves more study.

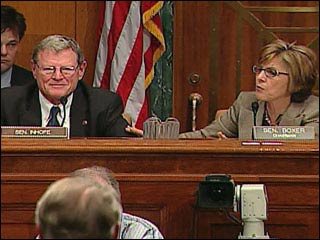

In fact, Inhofe considered it a grave enough threat that he recently co-sponsored a bill with Democratic Senators Carper, Boxer and Kerry to prod the EPA into studying the health and global warming impacts of black carbon emissions.

And while the insufferable Oklahoman may insist that his support for the legislation in no way contradicts his established denier bona fides – for good measure, he unleashed a typically scathing critique of the Obama administration’s proposed environmental policies the same day the bill was introduced – there is no denying that black carbon, the product of fossil fuel consumption and biomass burning, is a major agent of climate change.

A study published last year in Nature Geoscience (sub. required) determined that black carbon is second only to carbon dioxide in affecting climate change. The lead author, Veerabhadran Ramanathan, a prominent climate scientist based at UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography (and a co-recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore), wrote at the time that solar heating caused by soot emissions could contribute as much to the melting of glaciers and snowpacks in the Himalayas as CO2-induced warming.

Atmospheric brown clouds could also cut the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth’s surface, with potentially grave implications for the hydrological cycle, and reduce the reflectivity of snow and ice by changing their albedo. (The upside, though, is that they could also slightly cool the planet by blocking solar radiation.)

In a Nature study published in 2007, Ramanathan and a team of international researchers estimated that the clouds enhanced lower atmospheric warming by about 50 percent in Asia. “The combined warming trend of 0.25 K (kelvin) per decade may be sufficient to account for the observed retreat of the Himalayan glaciers,” they concluded. Recent studies have pegged black carbon’s contribution to global warming at 18 percent, compared to 40 percent for CO2.

In a recent speech at USC (you can download a video of his presentation here), Ramanathan lamented that the international community has been too single-mindedly focused on curbing CO2, identifying black carbon as one of several gases that would be much easier to deal with. “Some of these gases are easier to get rid of than carbon dioxide, and somehow that message has gotten lost in the current discussion of how to deal with the problem,” he said.

Unlike CO2, black carbon remains in the atmosphere for only a few weeks, making soot reduction – by replacing heavily polluting technologies with low-emission or solar-powered alternatives, for instance – a quick, easy climate fix. In India, Ramanathan said that emissions from small biomass-burning cookstoves make up almost 65% of all black carbon emissions.

It’s a fascinating talk, and one that I heartily recommend you watch in full – particularly the section in which he describes Project Surya, an ambitious effort to alleviate poverty, improve public health, and fight climate change by replacing soot-emitting cookstoves with cleaner-burning ones in India.

How would the bill proposed by Inhofe, Kerry and their colleagues address this problem? Though a little vague, it essentially directs the EPA to identify the largest sources of black carbon and most promising reduction technologies and to use that information to: a) find funding opportunities to reduce said emissions, and b) fund more R & D.

Granted, we’ll have to wait at least another year before the bill makes it to the Senate floor but, if even Inhofe is already on board, there’s a good chance that it’ll make its way through both houses of Congress. The only concern at this point is that the EPA seems undecided as to the contribution of black carbon to global warming (because of the cooling effect I mentioned earlier), as the WSJ’s Keith Johnson pointed out a few days ago:

“Like other aerosols, black carbon can also affect the reflectivity and lifetime of clouds. How black carbon and other aerosols, such as sulfates, alter cloud properties is a key source of uncertainty in quantifying the total human influence on the global climate. This total cloud indirect effect caused by all aerosols (e.g., sulfates, black carbon and organic carbon) is estimated to be causing a net cooling effect, with a large range of uncertainty. Given these reasons, there is considerably more uncertainty associated with black carbon’s warming effect compared to the estimated warming effect of the six long-lived greenhouse gases.”

While it may have played a role in mitigating the observed warming, black carbon is too much of a threat to leave out from climate regulations.

Go here to find out more details about DeSmogBlog’s monthly book give-away.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts