Note: This post is part of an ongoing series about North American pipelines. For an introduction and links to the wide-ranging coverage–from safety to legal issues to the business and economics to vulnerabilities–see this regularly-updated intro post.

On Monday, the House passed a bill that would force the Obama administration to make a final decision on TransCanada’s controversial Keystone XL pipeline by November 1. The Keystone XL project (which regular DeSmogBlog readers should be familiar with) would funnel tar sands oil from Alberta’s massive reserves down to Gulf Coast refineries in Texas.

This isn’t the place to discuss in too much depth the various and plentiful problems with Alberta tar sands itself – from extraction to transportation to refining to combustion, it’s the dirtiest oil on the planet. From a climate perspective, the Alberta tar sands contain enough carbon to lock the planet into climate chaos. In the words of NASA climatologist Jim Hansen, “if the tar sands are thrown into the mix it is essentially game over.”

Because Keystone XL is so controversial, and because its construction could be such a tipping point in the climate fight, a broad and diverse coalition of scientists and activists are digging in their heels for a big fight, and planning a multi-week action at the White House. (Here’s more on how to get involved.)

But since this is a post about pipelines, I’m going to focus on how tar sands pipelines are different than those that carry conventional crude, how they’re much more prone to leaks and spills, and how those spills are particularly bad for the environment.

First, you need to understand what – physically and chemically – tar sands actually is. According to the Bureau of Land Managment, tar sands

Once upon a time, the tar sands oil that flowed through North American pipelines was in the form of a synthetic crude. In other words, the sticky, viscous tar sands bitumin was upgraded to a more free-flowing form of crude before entering the pipes. But recently, the industry has found it cheaper and easier – if not as safe or stable – to dilute the bitumen with liquid natural gas, creating a substance called diluted bitumen, or “DilBit.”

A joint report by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), the Pipeline Safety Trust, the National Wildlife Federation and the Sierra Club, released in February, spotlights the specific hazards of pipelines carrying this tar sands “DilBit.”

The report describes DilBit as “a highly corrosive, acidic, and potentially unstable blend of thick raw bitumen and volatile natural gas liquid condensate.”

Testifying this past Tuesday in front of the House Energy and Commerce’s Energy and Power Subcommittee, NRDC expert Anthony Swift laid out the specific risk of this DilBit to the pipelines themselves:

Besides the heat, both Swift’s testimony (PDF) and the joint pipeline report warn that DilBit has higher sulfur and chloride salt contents, both of which can lead to corrosion and cracking. There’s also high levels of quartz, rutile, and pyrite particles, all of which are highly abrasive. The “Tar Sands Pipeline Safety Risks” report specifies that diluted bitumen:

- is more acidic, thick, and sulfuric than conventional crude oil;

- is up to seventry times more viscous than concentional crudes;

- contains fifteen to twenty times higher acid concentrations than conventional crudes and five to ten times as much sulfur as conventional crudes, and that “the additional sulfur can lead to the weakening or embrittlement of pipelines.”

What’s more, due to an unfortunate quirk of DilBit’s chemical composition, underground leaks can be much more difficult for monitors to detect. (If you’re curious about the finer points of this chemistry, check out the joint Tar Sands Pipeline Safety Risks report (PDF).)

So enough with the unfortunate chemistry of DilBit; we also have some empirical evidence to look at. With even a relatively short history, there are already plenty of spills and leaks involving DilBit, many of which have been covered here on DeSmogBlog.

The Keystone I pipeline (the first in TransCanada’s Keystone system that could eventually include Keystone XL) has infamously spilled 12 times in under a year of operation. (This despite assurances from the company that leaks would occur from Keystone only “once every seven years.”)

A May breach at a North Dakota pumping station spewed over 500 barrels, like a geyser, into the air. Local landowner Bob Banderet noted the discrepancy between TransCanada’s predictions and the reality: “They said this couldn’t happen,” Banderet said. “It’s a once in a thousand year occurence, and here it is right in front of you.”

There’s more. In 2006, corrosion in Alberta’s Rainbow pipeline caused over 343,000 gallons of oil to leak near Slave Lake, as Emma Pullman reported earlier here. Almost exactly a year ago this week, roughly 800,000 gallons of DilBut spilled into the Kalamazoo River in Western Michigan from a pipeline owned by the Canadian company Enbridge. In fact, in 2010, Enbridge’s Lakehead system spilled over a dozen times, accounting for more than half of all crude spilled in the United States last year.

Even that recent, awful Exxon Mobil spill that spoiled the “last great river,” the Yellowstone River, has ties to tar sands. Exxon Mobil officials admitted earlier this month that the Silvertip pipeline “routinely transported” tar sands oil.

Finally, after the tar sands oil does inevitably spill, cleanup is a heck of a lot harder than normal crude spills. There’s proof in Western Michigan. Reporter Kari Lydersen traveled to Marshall, Michigan to report on cleanup efforts a year later that Enbridge spill. Her report for OnEarth is sobering:

When that combination, known as DilBit, spilled out of the ruptured pipeline, the benzene and other chemicals in the mixture went airborne, forcing mandatory evacuations of surrounding homes (many of which were later bought by Enbridge because their owners couldn’t safely return), while the thick, heavy bitumen sank into the water column and coated the river and lake bottom, mixing with sediment and suffocating bottom-dwelling plants, animals, and micro-organisms.

Surface skimmers and vacuums were no help, and a full year later, EPA officials and scientists are still working on a plan to remove submerged oil from about 200 acres of river and lake bottom. EPA officials had given Enbridge an August 31 deadline to get all the oil out, but they now say a full cleanup could take years. “Where we thought we might be winding down our piece of the response, we’re actually ramping back up,” said Mark Durno, one of EPA’s on-scene coordinators. “The submerged oil is a real story – it’s a real eye-opener. … In larger spills we’ve dealt with before, we haven’t seen nearly this footprint of submerged oil, if we’ve seen any at all.”

Setting aside all the other threats and hazards posed by tar sands, there remains the basic, physical truth that contemporary pipelines simply cannot safely and securely transport its diluted bitumen form. And when the DilBit does spill, it is a much bigger problem than the already devastating impacts of spilled crude.

Still, according to the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers’ numbers, American imports of DilBit have increased five fold over the past decade. If the Keystone XL project is approved and built, that number will only rise, and so will the number of spills, and the public costs of dealing with them.

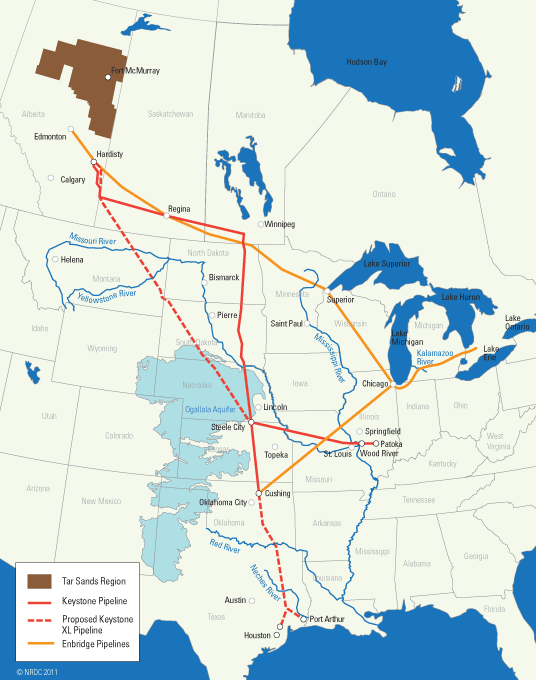

MAPS OF TAR SANDS PIPELINES IN THE U.S.

Here is a map put together by NRDC of the existing and proposed tar sands DilBit pipelines:

For a closer look at the network of existing and proposed tar sands pipelines and refineries, download this map [PDF] put together by NoDirtyEnergy.org.

Photo credit: National Transportation Safety Board

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts